|

A 65-year-old white male with corneal ectasia s/p penetrating keratoplasty (PK) in both eyes was referred from the cornea service for specialty contact lens evaluation. His chief complaint was that he “doesn’t want surgery.”

His medical history and systemic medications were non-contributory, and he wasn’t on any ocular medications. Besides s/p PK and corneal ectasia OU, his ocular history was positive for grade 3 nuclear sclerotic cataracts OU.

Case

The patient had PK “in the 1970s,” after which point he was lost to follow-up. He had deferred surgery for both cataract extraction and repeat corneal transplantation.

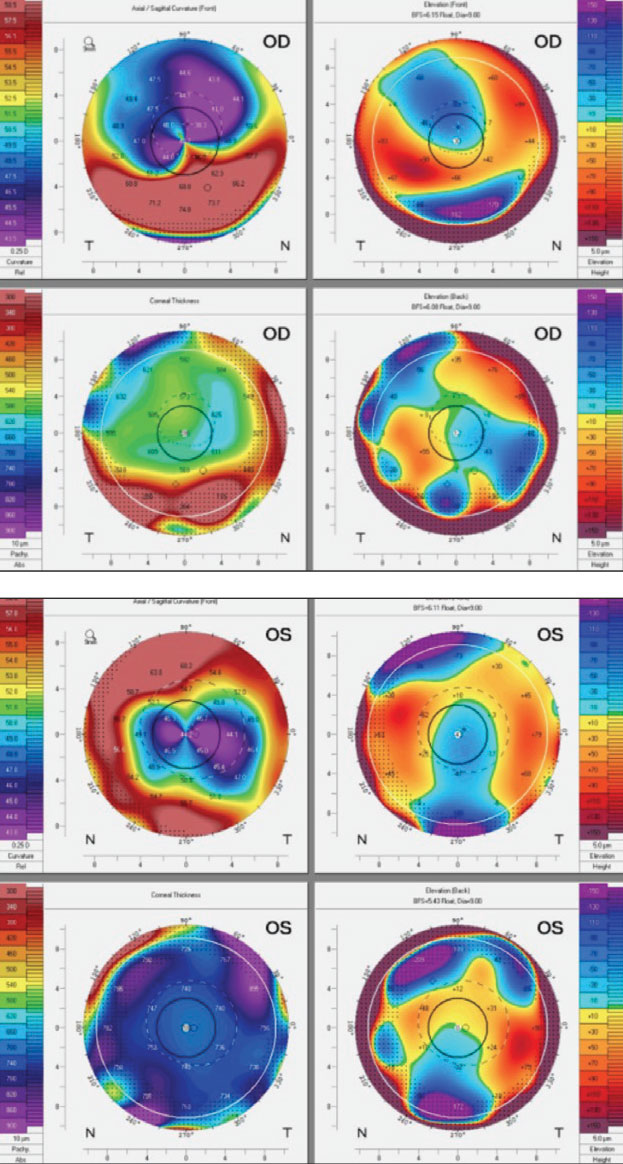

He presented to us with a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/60- OD and 20/300 OS in his spectacles. Pachymetry readings showed 660µm OD and 735µm OS. Unfortunately, his corneal endothelial cell count readings were unreliable due to the irregularity of his corneas, giving values of 140mm2 OD and 844mm2 OS.

Contributory slit lamp exam findings included the following (all other findings were within normal limits):

• Eyelids/adnexa: floppy eyelid, meibomian gland dysfunction, incomplete blink OU.

• Cornea: PK graft with ectasia, thin and ectatic inferior cornea (host and ~1.5mm of donor button), mild stromal haze and peripheral suture scars, punctate epithelial erosions, irregular surface OD, keratoglobus OS.

• Lens: grade 3+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts OU.

|

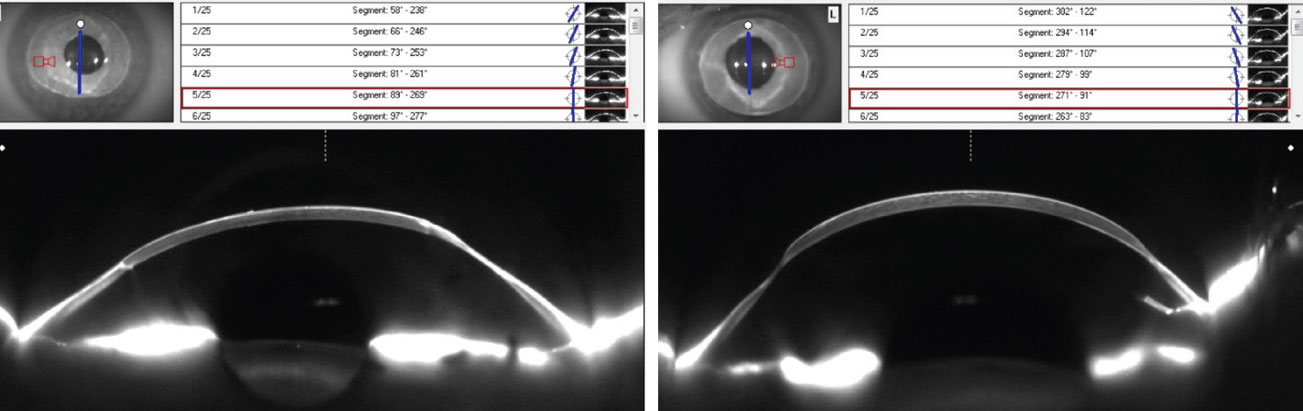

OCT imaging of the right and left eyes, respectively. Click image to enlarge. |

Considerations

Here, we highlight how we would proceed.

Dr. Su. Cases like this can be tricky. Transplants that have scarred, failed or produced inadequate vision can typically be replaced multiple times in a patient’s lifetime as long as the patient can tolerate additional procedures and there is a reasonable chance of success. In this case, the patient was adamant about deferring surgery, so the best we could do was prolong his current grafts.

Generally, wearing contact lenses doesn’t increase the likelihood of corneal graft rejection, but complications of lens wear can. Whether a using soft or a gas permeable (GP) lens, high Dk material is important to help minimize the risk of hypoxic-related complications. Lenses can also lead to mechanical irritation of the cornea, especially if the lens interacts with an exposed suture.

With this patient’s level of irregularity, it is unlikely that a standard soft or custom soft lens would be successful. In this case, a scleral lens may best accommodate the corneoscleral shape, but a corneal rigid GP lens may allow for better tear exchange. However, given the irregularity, success with a standard corneal GP is unlikely.

Scleral lens wear decisions should keep endothelial cell health in mind, especially with grafts over 50 years old. Patient motivation is also crucial for scleral lens success, and since the patient is apprehensive about the application and removal process, it adds another challenge for successful scleral lens wear. It may seem like surgery is the only option, but luckily there are advanced lens technologies that can create custom-designed lenses derived from scans or impressions. In this case, a data-driven lens to make a corneal GP may give the patient the best chance of success.

Dr. Gelles. Old grafts with significant irregularity can pose a real challenge. There are no perfect options; both scleral and corneal GPs have problems. GPs aren’t going to stay on the eye, and corneal edema has been well-documented with sclerals in post-PK corneas. We know endothelial cell density decreases over time after successful PK. For years, a rule of thumb has been propagated about low endothelial cell counts (sub-1000) and scleral-induced edema, but it’s not “how many cells?” that matters, it’s “how well do they function?” to keep the cornea clear.

In patients needing a scleral lens where the endothelial function may be compromised, such as in old grafts, a “scleral lens challenge” can be performed to gauge the probability of wear-induced complications. This includes in-office monitoring, where a scleral lens is worn for a few hours during the initial fitting. If signs of complications, such as reduced vision, Sattler’s veil, microcystic edema, bullae, folds or increased corneal thickness, are present in that short period of time, then a scleral lens is likely not an ideal option. If a scleral is a must, it will require significant modifications (increase material Dk, decrease lens thickness, reduce corneal clearance, fit for tear exchange, add channels and fenestrations and/or reduce wear time) to mitigate the response.

If we can limit the physiologic stress of scleral lens wear on the cornea, we can minimize potential issues, but this takes significant skill and time. Add in a patient who’s not confident in application and removal, and this venture is unlikely to succeed.

A corneal GP would be a better option health-wise—if you can keep it on the eye. We all know that highly irregular corneas are very challenging to fit with standard diagnostic fitting set–driven corneal GP designs. However, technology has evolved considerably; by using data from corneal topographers, tomographers, profilometers or 3D models derived from ocular impressions, lenses can be made with extremely complex geometries. These freeform GP lenses can be created to follow the contour of complex eyes to remain in proper position with adequate movement and tear exchange. For this patient, a data-driven GP is likely the best option.

Dr. Noyes. From a clinical perspective, this patient was not a candidate for scleral contact lenses due to his endothelium quality (his grafts were over 50 years old), and from a scleral lens insertion and removal perspective, he did not feel he could adequately complete the process.

Traditional rigid GP lenses are also not a good option due to the massive amount of ectasia and corneoscleral irregularity in this case. These irregularities were so severe that when using diagnostic lenses in-office, none could stay on the eye for more than a few seconds. A freeform profile is necessary to combat these issues, particularly in highly ectatic and irregular grafts.

|

Scheimpflug imaging of the right (top) and left eyes (bottom). Click image to enlarge. |

Results

Ocular impressions were taken using an impression system (Blue Goo, EyePrint Prosthetics). These molds were then 3D-scanned to create digital models of each cornea. To mirror the corneal shape, lens design software was used to create custom freeform GP lenses (EyeprintPro, EyePrint Prosthetics). For reference, these lenses had a very deep sagittal depths (2539µm OD and 2677µm OS) for their diameters (10.0mm OD and 9.0mm OS).

Additionally, the lenses were made of high Dk material (Optimum Extra, Contamac). Despite some non-pathologic central bearing and minor edge lift at times, the patient’s lenses could stay on his eyes, and he had clear, comfortable vision. For a visual, click here. His vision improved to 20/25 OD and 20/20 OS, and no further lens modifications or revisions were needed.

Takeaways

This case highlights the importance of adopting technology in contact lens practice. The technology-driven contact lens design method we used created corneal GP lenses with a level of success surpassing our expectations. This process unlocks the door for a much wider range of complexity that a corneal GP can accommodate and is particularly useful in the case of scleral lens contraindication.

These technology-driven lenses are an additional tool we can use to help further improve the life and vision of our patients.

Special thanks to David Slater, of NCLEC, for providing images, video and consultation on designing this lens.

Dr. Su is the Cornea and Contact Lens Fellow at the Cornea and Laser Eye Institute (CLEI) Center for Keratoconus. She has no financial interests to disclose.