Contact lens wear is the most significant risk factor for infectious microbial keratitis, which can result in significant visual morbidity and permanent vision loss.1 Historically, disease incidence had been five times higher in extended soft contact lens wearers than in daily soft contact lens wearers—20.9 and 4.1 per 10,000 persons, respectively.2 Recent literature, however, suggests a rise in both the number and severity of contact lens-related infections.3-7 Possible explanations for this change include the increasing number and younger ages of contact lens wearers, expanding popularity of orthokeratology and the shift from use of peroxide-based disinfecting solutions to multipurpose solutions.8

Though bacteria are responsible for the majority of cases of contact lens-related microbial keratitis, infections caused by fungal and protozoan organisms are often more difficult to treat, more likely to result in poor clinical outcomes such as corneal perforation, and are more likely to require surgical intervention.9 Both organisms penetrate deeply into the corneal stroma.

Fungi gain access through an epithelial defect and are capable of crossing an intact Descemet’s membrane to reach the anterior chamber. Fusarium, a filamentous septated fungus, is the most common cause of contact lens-related fungal keratitis, followed by Aspergillus and Candida. In contrast, protozoa like Acanthamoeba gain entry by attaching to the corneal epithelium and producing proteases that destroy corneal tissue. The motile trophozoite can also encyst rapidly into a double-walled configuration that is highly resistant to destruction. These infections are hard to eradicate as a result of both deeper invasion into the cornea and poor penetration of antifungal and amoebicidal medications.

In the recent past, two outbreaks involving Fusarium and Acanthamoeba keratitis were associated with contact lens solutions. More specifically, ReNu with MoistureLoc (Bausch + Lomb) was implicated in the outbreak of Fusarium keratitis in 2006, which was first reported in Singapore and Hong Kong.10 A year later, Complete MoisturePlus (AMO) was found to have been involved in the outbreak of Acanthamoeba keratitis from 2003 to 2006.11 With the offending contact lens solutions withdrawn from the market, contact lens-related Fusarium infections declined.5,12 Conversely, Acanthamoeba infections remain high.13,14 Acanthamoeba keratitis has risen 10-fold from previous estimates of 1.65 to 2.01 cases per one million contact lens wearers to 20 cases per one million contact lens wearers.4,13 This increase has prompted the search for yet unidentified risk factors. Recent research, however, has failed to provide any significant insight.4 In fact, none of the current practical contact lens disinfecting systems are able to kill the Acanthamoeba cyts.15

To date, the etiology to explain this rising trend in Acanthamoeba keratitis remains indeterminate.

Risk Factors

Overnight contact lens wear remains one of the leading causes of corneal ulcers despite advancement in contact lens technology.3 In a recent Centers for Disease Control (CDC) survey, half of contact lens wearers report sleeping in their lenses overnight.16 Other risk factors include poor storage case hygiene, infrequent storage case replacement and solution type.17 Daily disposable contact lens wear may reduce the severity of corneal ulcers and lead to better visual outcomes.3,18,19 Fungal keratitis can also result from trauma, especially trauma with exposure to organic matter. Chronic steroid use with exposure to contaminated water or soil while wearing contact lenses or after trauma can also lead to Acanthamoeba keratitis.8.20

| |

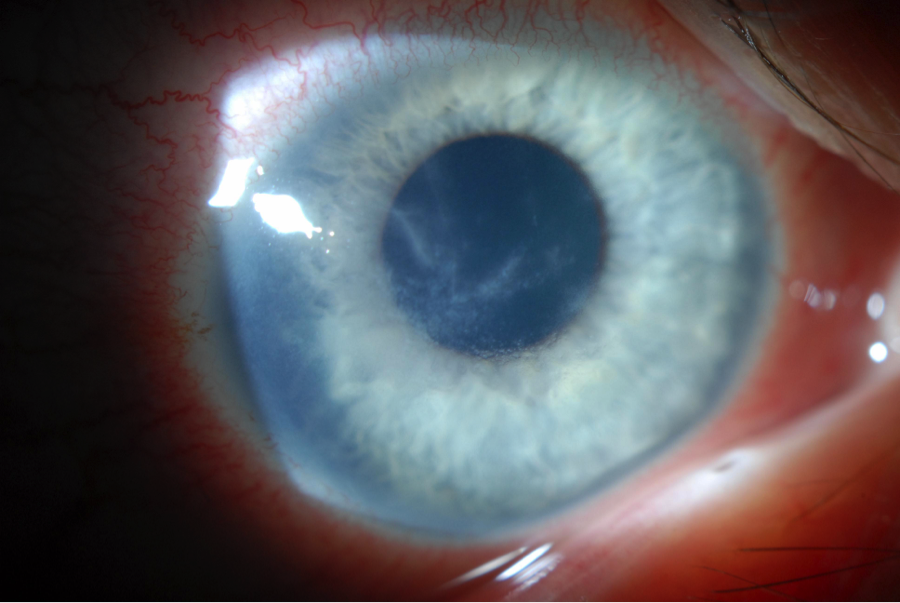

| Fig. 1. Pseudodendritiform appearance in Acanthamoeba keratitis, often misdiagnosed as HSV keratitis. | |

| |

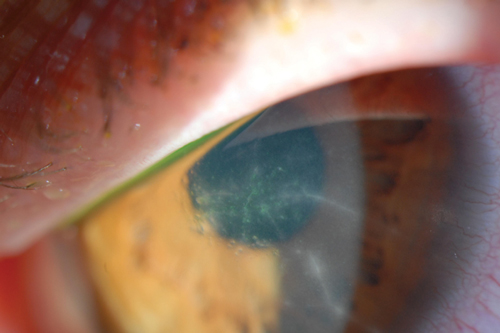

| Fig. 2. Radial perineuritis seen in Acanthamoeba keratitis. | |

| |

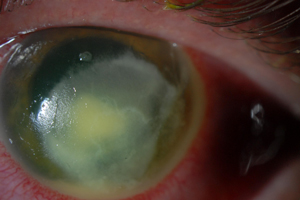

| Fig. 3. Leathery or dry infiltrate with endoplaque in fungal keratitis. |

Identification

A timely diagnosis is beneficial and often leads to a more favorable outcome. However, it is common for a delay to occur in the diagnosis of infections related to fungi or Acanthamoeba, as these are often misdiagnosed as bacterial or herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections (Figure 1). Significant delay in diagnosis ranging from 27 to 43 days has been observed particularly in Acanthamoeba keratitis.6,7 Proper diagnosis is paramount, as delays in treatment coupled with an advanced disease state can lead to poorer visual outcomes and increased need for surgical intervention.6,7,21-23

Early Acanthamoeba keratitis often presents with a dendritiform keratitis or a nonspecific keratitis. As such, two-thirds of these patients are misdiagnosed as having HSV keratitis.24 Pain out of proportion to clinical findings—a classic indication of Acanthamoeba keratitis—can be used to differentiate between the two. However, some patients do not present with such impressive pain.6,25 Thus, the possibility of Acanthamoeba keratitis should be considered in any patient with a history of contact lens wear and presumed HSV infection. If the patient does not have a typical response to antiviral medications, then the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis should be sought. Radial perineuritis is a finding that greatly enhances the suspicion for Acanthamoeba keratitis (Figure 2). A ring infiltrate is a later finding in Acanthamoeba keratitis, which has a classic appearance but poorer prognosis than these earlier signs.

Fungal keratitis may also present with a dendritiform appearance, multifocal lesions, feathery bordered infiltrates and satellite lesions.8,25,26 The infiltrates may have a leathery or dry appearance and often are deep in the stroma (Figure 3). Fungal infections often have impressive anterior chamber inflammation with endothelial plaque and hypopyon.8,25 Despite this inflammation, they often have less lid edema and hyperemia than classically seen with bacterial infections.

Work-Up Protocols

In cases of suspected infectious keratitis, corneal scrapings should be obtained for gram stain and cultures with blood agar, chocolate agar, Sabouraud dextrose agar and thioglycolate broth. If a fungal infection is suspected, corneal scrapings should also be sent for additional Grocott–Gomori methenamine silver stain, potassium hydroxide, lactophenol cotton blue, Giemsa or calcafluor white.8,25 Sabouraud dextrose agar is the preferred medium for fungi, though it can also grow on chocolate agar and blood agar.8,25 Fungal cultures should be kept for a minimum of two weeks.8,25

Corneal scrapings in ulcers suspicious for Acanthamoeba should be sent for additional Giemsa, periodic acid-Schiff, hematoxylin and eosin, Wright’s, calcofluor-white or acridine orange stains to identify trophozoites or cysts.27 Acanthamoeba is best plated on nonnutrient agar with an Escherichia coli or Enterobacter aerogenes overlay.27,28 Scrapings and cultures are helpful early in the disease when the infection is more superficial, but once the infection has advanced deeper into the corneal stroma, a corneal biopsy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.27 Corneal biopsies may also be useful in monitoring treatment success or complete resolution of the infection, as this can often be difficult to ascertain clinically.

Confocal microscopy, if available, may hasten diagnosis of fungal hyphae and Acanthamoeba cysts. It can be particularly useful in cases when the infiltrates are deep and not accessible by corneal scrapings.29 A prospective observational clinical study found the sensitivity and specificity of confocal microscopy to be 88.3% and 99.1%, respectively, when diagnosing either fungal or Acanthamoeba keratitis.29 However, equipment expense and necessary staff training can limit use of this technology. Polymerase chain reaction testing is another option for diagnosing both fungal and Acanthamobea infections that may yield results sooner than cultures; however, this test is not yet widely available.20,25

| Table 1. Antifungal Agents | |||

| Concentration/Dose | Class | Usage | |

| Topical | |||

| Natamycin | 5% up to Q1hr | Polyene |

|

| Amphotericin B | 0.15% up to Q1hr | Polyene |

|

| Voriconazole | 1% up to Q1hr | Triazole |

|

| Systemic | |||

| Voriconazole | 200mg PO BID | Azole |

|

| Itraconazole | 200mg to 400mg PO BID | Azole |

|

| Fluconazole | 200mg to 400mg PO BID | Bistraizole |

|

| Ketoconazole | 200mg PO BID | Azole |

|

| Intrastromal | |||

| Voriconazole | 50µg/0.1mL* | Triazole |

|

| Intracameral | |||

| Amphotericin B | 50µg to 10µg in 1mL of 5% dextrose | Polyene |

|

| Voriconazole | 50µg/0.1mL* | Triazole |

|

| *Reconstituted with 2mL of lactated Ringer's solution to a concentration of 0.5mg/mL. | |||

Fungal Treatment

In severe fungal keratitis, consider treatment with multiple medications, such as a combination of two topical antifungal agents or the addition of an oral agent.8,30 Note, however, no consensus exists on the preferred treatment regimens, the best single antifungal agent or best combination therapy.29,31 Natamycin was found in the MUTT trial to be more efficacious than voriconazole in treating filamentous fungi such as Fusarium or Aspergillus.9 In cases of nonseptated fungal infections such as Candida, topical amphotericin B or voriconazole may be preferred. In recalcitrant cases, intrastromal injection of voriconazole or intracameral injection of amphotericin B or voriconazole may be considered. Topical cycloplegics can alleviate pain and prevent formation of synechiae in cases when anterior chamber inflammation is pronounced. Coexistent elevation of intraocular pressure or glaucoma portends a worse prognosis and should be aggressively treated.

Therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty (PK) is usually reserved for fungal ulcers that have been refractory to medical treatment or that have resulted in corneal perforation. Tissue adhesives such as cyanoacrylate glue or amniotic membrane may be used in cases of impending perforation to allow antifungal medications to be given for a period of time prior to surgery. Studies show that PK is effective and can result in good vision, but is often plagued by recurrence of fungal infection, a higher rate of graft failure and secondary glaucoma.29

Interest in corneal collagen crosslinking (CXL) as a means to treat infectious keratitis has grown recently, particularly in cases of corneal melting. CXL may be beneficial through its direct cytotoxic action, enhancement of corneal integrity and reduction of the inflammatory response. However, studies suggest no difference between CXL and current treatment modalities in speeding resolution of mycotic keratitis or reducing adverse outcomes like corneal perforation.32,33

| Table 2. Amoebcidal Agents | |||

| Concentration/Dose | Class | Usage | |

| Topical | |||

| Chlorhexidine | 0.02% up to Q1hr | Antiseptic |

|

| Polyhexamathylene biguanide (PHMB) | 0.02% up to Q1hr | Antiseptic |

|

| Propamidine (Brolene) | 0.1% up to Q1hr | Diamidine |

|

| Hexamidine | 0.1% up to Q1hr | Diamidine |

|

| Systemic | |||

| Voriconazole | 200mg PO BID | Azole |

|

| Itraconazole | 200mg to 600mg PO per day (BID dosing) | Azole |

|

| Ketoconazole | 200mg to 600mg PO per day (BID dosing) | Azole |

|

| Pentamidine | 190mg to 400mg/day IV | Diamidine |

|

Protozoa Treatment

When treating Acanthamoeba keratitis, dual coverage—with one antiseptic (e.g., chlorhexidine or PHMB) and one diamidine (e.g., propamidine or hexamindine)—is usually started with hourly around-the-clock dosing for the first few days.27 Frequent dosing early on can help destroy trophozoites before cysts are established, but can also be toxic to the epithelium.20 Treatment should be tapered based on clinical response and tailored individually.27 Cycloplegic agents, oral nonsteroidals or oral narcotic medications can be used for pain control.

The use of topical corticosteroids is controversial.20,27,34 Steroids help control inflammation when severe pain, scleritis or significant anterior chamber reaction is present.27 They may reduce pain and improve anterior chamber inflammation without increasing the rate of medical treatment failure in cases when diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis was not delayed and when corticosteroids were initiated in conjunction and after use of amoebicidal medications.34 Steroids are used cautiously and sparingly because they can weaken the host’s immune system, promote excystment (cyst to trophozoite) and proliferation of trophozoites.35 It is not clear whether or not steroids prevent encystment (trophozoite to cyst), which may be beneficial in the early stages of treatment.34

In our experience, topical corticosteroids are initiated after four to six weeks of amoebicidal treatment and, importantly, without discontinuing the use of amoebicidal agents during use.24 Amoebicidal agents should be continued for at least a few weeks after topical corticosteroids have been discontinued.20,27,34

In more advanced cases of Acanthamoeba keratitis—e.g., sclerokeratitis—systemic use of oral antifungal agents with anti-amoebic activity such as voriconazole, itraconazole or ketoconazole in addition to oral corticosteroids or systemic immunosuppressants can be used as an adjunct to topical treatment.20,36

Persistent epithelial defect is a common problem in severe Acanthamoeba keratitis. The toxicity of topical antiseptic and diamidine to the corneal epithelium is well known. Streptococcus is a common organism associated with bacterial superinfection in Acanthamoeba keratitis.24 Prophylactic use of antibacterial drugs should be used to prevent bacterial superinfection.20 Amniotic membrane transplant can help with re-epithelialization.20,37

Therapeutic PK is a last resort in cases of corneal perforation or progressive corneal and scleral melt. Success of the graft is typically higher when the infection is localized and inflammation is controlled prior to surgery.27,38,39 Attempts to delay surgery and prolong management with anti-amoebic agents can be achieved at times with amniotic membrane transplant or gluing.27 It is important for the corneal surgeon to trephinate beyond clinical areas of infiltrate and satellite lesions during surgery to ensure organism elimination.39 Patients should continue to use amoebicidal agents for several months after surgery to kill any residual organisms. Optical PK should be considered for cases of corneal scarring or central irregular astigmatism after infection, as the procedure has a much higher success rate in terms of graft survival and visual outcomes as compared to therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty. Practitioners should monitor for signs of recurrent infection for a minimum of three months after ceasing amoebicidal agents.40

An Ounce of Prevention… 1. Never sleep or nap in contact lenses. |

Microbial keratitis is an uncommon infection that can result from contact lens wear. Atypical infections from fungal and protozoan organisms are often difficult to diagnose and treat, and have poorer visual outcomes. It is crucial to maintain a high level of suspicion for atypical infections so that the diagnosis is not delayed and treatment can be initiated promptly.

Dr. Cheung is a cornea fellow at Wills Eye Hospital. She graduated medical school from Alpert Medical School of Brown University and completed her ophthalmology residency at University Hospitals Case Medical Center.

Dr. Hammersmith is an attending surgeon on the Corneal Service and director of the Cornea Fellowship Program at Wills Eye Hospital. She is also an associate professor at the Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University.

1. Dart JK, Stapleton F, Minas Sian D. Contact lenses and other risk factors in microbial keratitis. Lancet 1991;338:650–3.

2. Poggio EC, Glynn RJ, Schein OD, et al. The incidence of ulcerative keratitis among users of daily-wear and extended-wear soft contact lenses. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:779–783.

3. Yildiz EH, Airiani S, Hammersmith KM, et al. Trends in contact lens-related corneal ulcers at a tertiary referral center. Cornea. 2012 Oct;31(10):1097-102.

4. Tu EY. Acanthamoeba keratitis: a new normal. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014 Sep;158(3):417-9.

5. Gower EW, Keay LJ, Oechsler RA, et al. Trends in fungal keratitis in the United States, 2001 to 2007. Ophthalmology 2010; 117: 2263–2267.

6. Ross J, Roy SL, Mathers WD, et al. Clinical characteristics of Acanthamoeba keratitis infections in 28 states, 2008 to 2011. Cornea. 2014 Feb;33(2):161-8.

7. Thebpatiphat N, Hammersmith KM, Rocha FN, et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis: a parasite on the rise. Cornea. 2007 Jul;26(6):701-6.

8. Iyer SA, Tuli SS, Wagoner RC. Fungal keratitis: emerging trends and treatment outcomes. Eye Contact Lens. 2006 Dec;32(6):267-71

9. Sun CQ, Lalitha P, Prajna NV, et al. Association between in vitro susceptibility to natamycin and voriconazole and clinical outcomes in fungal keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2014 Aug;121(8):1495-500.

10. Khor W, Aung T, Saw S, et al. An outbreak of Fusarium keratitis associated with contact lens wear in Singapore. JAMA 2006; 295:2867–2873.

11. Patel A, Hammersmith K. Contact lens-related microbial keratitis: recent outbreaks. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008 Jul;19(4):302-6.

12. Grant GB, Fridkin S, Chang DC, Park BJ. Postrecall surveillance following a multistate fusarium keratitis outbreak, 2004 through 2006. JAMA. 2007 Dec 26;298(24):2867-8.

13. Yoder JS, Verani J, Heidman N, et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis: the persistence of cases following a multistate outbreak. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2012;19(4):221–225.

14. Schaumberg DA, Snow KK, Dana MR. The epidemic of Acanthamoeba keratitis: where do we stand? Cornea 1998; 42:493–508.

15. Shoff ME, Joslin CE, Tu EY, et al. Efficacy of contact lens systems against recent clinical and tap water Acanthamoeba isolates. Cornea 2008;27(6):713–9.

16. Cope JR, Collier SA, Rao MM, et al. Contact lens wearer demographics and risk behaviors for contact lens-related eye infections - United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015 Aug 21;64(32):865-70.

17. Stapleton F, Edwards K, Keay L, et al. Risk factors for moderate and severe microbial keratitis in daily wear contact lens users. Ophthalmology. 2012 Aug;119(8):1516-21.

18. Stapleton F, Keay L, Edwards K, et al. The incidence of contact lens-related microbial keratitis in Australia. Ophthalmology. 2008 Oct;115(10):1655-62.

19. Dart JK, Radford CF, Minassian D, Verma S, Stapleton F. Risk factors for microbial keratitis with contemporary contact lenses: a case-control study. Ophthalmology. 2008 Oct;115(10):1647-54, 1654.e1-3.

20. Dart JK, Saw VP, Kilvington S. Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis and treatment update 2009. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009 Oct;148(4):487-499.

21. Bouheraoua N, Gaujoux T, Goldschmidt P, et al. Prognostic factors associated with the need for surgical treatments in acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea. 2013 Feb;32(2):130-6.

22. Qian Y, Meisler DM, Langston RH, Jeng BH. Clinical experience with Acanthamoeba keratitis at the Cole eye institute, 1999-2008. Cornea. 2010 Sep;29(9):1016-21.

23. Tu EY, Joslin CE, Sugar J, et al. Prognostic factors affecting visual outcome in Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2008 Nov;115(11):1998-2003.

24. Chew HF, Yildiz EH, Hammersmith KM, et al. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors associated with acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea. 2011 Apr;30(4):435-41.

25. Ansari Z, Miller D, Galor A. Current Thoughts in Fungal Keratitis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2013 Sep 1;7(3):209-218.

26. Knape RM, Motamarry SP, Sakhalkar MV, et al. Pseudodendritic fungal epithelial keratitis in an extended wear contact lens user. Eye Contact Lens. 2011 Jan;37(1):36-8.

27. Hammersmith, KM. Diagnosis and management of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 17:327–331.

28. Francine Marciano-Cabral, Guy Cabral. Acanthamoeba spp. as agents of disease in humans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003 April; 16(2): 273–307.

29. Vaddavalli PK, Garg P, Sharma S, et al. Role of confocal microscopy in the diagnosis of fungal and acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118:29–35.

30. Kredics L, Narendran V, Shobana CS, et al. Filamentous fungal infections of the cornea: a global overview of epidemiology and drug sensitivity. Mycoses. 2015 Apr;58(4):243-60.

31. FlorCruz NV, Evans JR. Medical interventions for fungal keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 9;4:CD004241.

32. Vajpayee RB, Shafi SN, Maharana PK, et al. Evaluation of corneal collagen cross-linking as an additional therapy in mycotic keratitis. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2015 Mar;43(2):103-7.

33. Uddaraju M, Mascarenhas J, Das MR, et al. Corneal Cross-Linking as an Adjuvant Therapy in the Management of Recalcitrant Deep Stromal Fungal Keratitis: A Randomized Trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015 Jul 9.

34. Park DH, Palay DA, Daya SM, et al. The role of topical corticosteroids in the management of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea. 1997 May;16(3):277-83.

35. McClellan K, Howard K, Niederkorn JY, Alizadeh H. Effect of steroids on Acanthamoeba cysts and trophozoites. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001 Nov;42(12):2885-93.

36. Iovieno A, Gore DM, Carnt N, Dart JK. Acanthamoeba sclerokeratitis: epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2014 Dec;121(12):2340-7.

37. Beucier T, Patteau F, Borderie V. Amniotic membrane transplantation for the treatment severe Acanthamoeba keratitis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2004;39:621–631..

38. Lorenzo-Morales J, Khan NA, Walochnik J. An update on Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. Parasite 2015, 22, 10.

39. Nguyen TH, Weisenthal RW, Florakis GJ, et al. Penetrating keratoplasty in active Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea. 2010 Sep;29(9):1000-4.

40. Awwad ST, Parmar DN, Heilman M, et al. Results of penetrating keratoplasty for visual rehabilitation after Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005 Dec;140(6):1080-1084.

41. Kalaiselvi G, Narayana S, Krishnan T, Sengupta S. Intrastromal voriconazole for deep recalcitrant fungal keratitis: a case series. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015 Feb;99(2):195-8.

42. Sharma N, Agarwal P, Sinha R, et al. Evaluation of intrastromal voriconazole injection in recalcitrant deep fungal keratitis: case series. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011 Dec;95(12):1735-7.

43. Sharma B, Kataria P, Anand R, et al. Efficacy profile of intracameral amphotericin B. The dften forgotten step. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2015 Jul 15.

44. Sacher BA, Wagoner MD, Goins KM, et al. Treatment of acanthamoeba keratitis with intravenous pentamidine before therapeutic keratoplasty. Cornea. 2015 Jan;34(1):49-53.