A clear-cut diagnosis of keratoconus (KCN) can be all a clinician needs to recommend corneal crosslinking (CXL) or rule out refractive procedures that may cause post-op issues in patients with corneal degenerations and dystrophies. However, not every diagnosis is obvious—there is often a gray area in which the individual doesn’t exhibit clinical signs of the disease but may still harbor latent KCN.

These gray areas can sometimes place doctors in tricky situations, as early detection of ocular conditions is always the best approach to stop future vision loss.

Enter AvaGen (Avellino), the first commercially available test of its kind to help identify patients at risk for developing KCN and certain other corneal dystrophies. The DNA test generates a polygenic KCN risk score based on the analysis of 75 KCN-related genes and more than 2,000 gene variants, according to the company.1 Since some ethnicities show a higher prevalence of this eye condition, the AvaGen test also factors this information into its results, the company says. The test is also purported to measure susceptibility of several corneal dystrophies, including epithelial basement membrane, granular, lattice, Reis-Bucklers, Schnyder and Theill-Behnke, Avellino states.1

“Genetic testing for KCN provides one more data point for determining risk of disease development,” says Aaron Bronner, OD, of Boise, ID. “Unlike previous ways of screening for the disease, genetic testing provides a look not only at current risk status but also future risk. This can be both helpful and confounding as clinical decisions are made.”

|

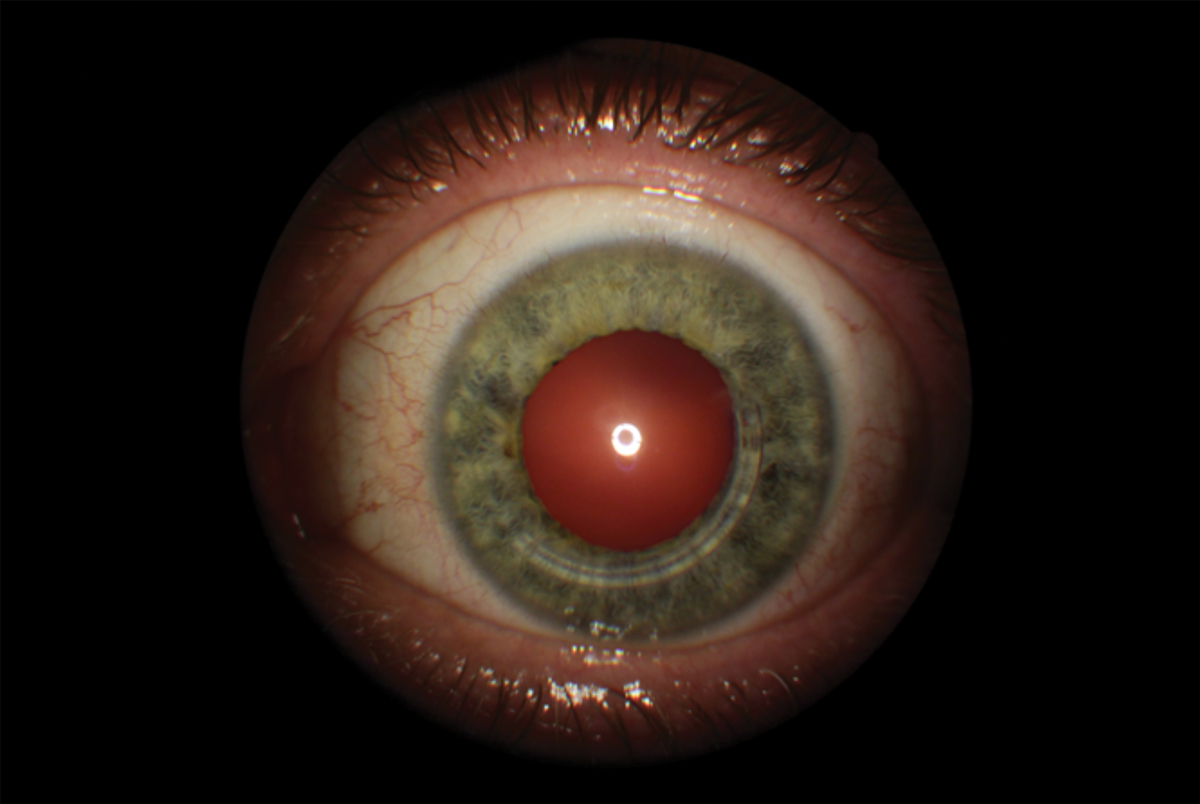

| Although genetic testing does not diagnose KCN, a positive risk profile could help recommend more frequent screenings or adjust treatment. Photo by Brian Chou, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

KCN Clues

On the screening front, KCN diagnostics have expanded and become even more refined in recent years.

For example, corneal tomography allows clinicians to evaluate the anterior and posterior cornea along with global pachymetry, says Melissa Barnett, OD, of UC Davis. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) can evaluate corneal epithelial thickness and wavefront aberrometry can be used to evaluate specific aberrations such as the third-, fourth- and fifth-order aberrations, especially vertical coma and trefoil. Also, corneal biomechanics can supply useful information to predict early KCN, she suggests.

“AS-OCT has certainly evolved to provide us much more information about the cornea in those at high risk or who actually have KCN, but their condition snuck by with traditional technologies,” adds Mile Brujic, OD, of Bowling Green, OH.

Currently the diagnosis of keratectasia at a mild stage—“the sweet spot” for doing something about it—requires Scheimpflug imaging, Dr. Bronner says.

Beyond the traditional and enhanced diagnostic tools available, numerous studies have supported the premise that genetics play a role into whether an individual may develop KCN.

One recent investigation included genetic screening in a large cohort of Chinese and Greek patients with KCN, and its researchers suggested variants in the VSX1 and TGFBI genes might be responsible for the condition through autosomal-dominant inheritance patterns with variable expressivity.2 The authors concluded that genetic screening is of great value in establishing a disease classification system of subclinical and early-stage KCN and for the preoperative screening of refractive surgery individuals to prevent postoperative corneal ectasia.2

Another relatively large KCN genome-wide association study used data from eye clinics in Australia, the United States and Northern Ireland. It reported the potential role of genes involved in apoptotic pathways and identified a genome-wide significant locus for KCN in the region of PNPLA2 on chromosome 11.3

Other research papers have found ethnicity plays a role in which populations may develop the disease.4-6 When comparing the risk of progression between East Asians, Europeans and Middle Eastern populations, one investigation found the latter group had the greatest risk, followed by Europeans and East Asians.4 Another recent investigation that looked at a US managed care network identified about 16,000 individuals with KCN. Its investigators found Black patients were 57% more inclined to develop KCN, followed by Latinos at 43%. Additionally, Asian Americans had 39% lower odds of developing KCN compared with Caucasians.7

My Early Experience with Genetic Testing for KCNRepeated results from one patient are oddly different.By Brian Chou, OD Genetic testing for keratoconus (KCN) is promoted as a new diagnostic tool. The opportunity is to move ahead of lagging disease indicators—like apical scarring, Vogt’s striae and Fleischer’s rings—to predictive heritable indicators of KCN. Having this information could help identify corneal crosslinking candidates and patients at greater risk for keratectasia after LASIK. I share my early clinical experience.

Genetics and KCNKCN has a well-known genetic link. A 2012 review article found that 6% to 23.5% of patients with KCN have a family member with it.1 Furthermore, studies have shown that relatives of KCN patients have a 15x to 67x higher risk of developing KCN.2 Several genome-wide association studies of KCN cases have confirmed previously identified genes and found several new susceptibility loci linked to KCN.3 External factors like eye rubbing and mechanical interaction of the cornea appear to combine with genetic predisposition to result in KCN.4 A case-control study of 33 KCN patients with highly asymmetric corneas and 64 controls found that vigorous eye rubbing and applying eye pressure during sleep were associated with the more afflicted eye.5 AvaGen by Avellino LabsIn February 2020, Avellino Labs introduced AvaGen, the first commercial genetic test to assess risk for KCN and detect the presence of certain corneal dystrophies. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Avellino Labs suspended producing and processing AvaGen tests until June 2021 when Avellino announced full nationwide availability of AvaGen.6,7 AvaGen involves collecting four noninvasive inner cheek (buccal) swab samples from the patient. Results typically arrive in two to four weeks. One outcome of AvaGen identifies the presence or absence of hereditary corneal dystrophies linked to the TGFBI gene: granular type 1 and type 2, epithelial basement membrane, lattice, Reis-Bücklers and Thiel-Behnke. These dystrophies are monogenic (i.e., caused by a single genetic mutation), and AvaGen is designed to yield a yes/no result for these. The KCN part of AvaGen is more complex because KCN is polygenic. Many genes encode for KCN, with environmental factors also having an influence. A polygenic risk score (PRS) devised by the company is returned on a scale of 0 to 100, where a PRS of 0 indicates no genetic risk. A higher AvaGen PRS is reported to indicate a greater genetic risk of developing KCN. Avellino says that AvaGen examines over 2,000 variants across 75 genes for KCN using whole-exome DNA sequencing, a fast and cost-effective technique to selectively sequence an individual’s DNA encoding for proteins or exons. Most genetic diseases are thought to show mutations in exons, so sequencing them can efficiently identify disease-causing mutations. All the exons in a genome make up an exome, which is understood to represent about 1% of a person’s DNA.

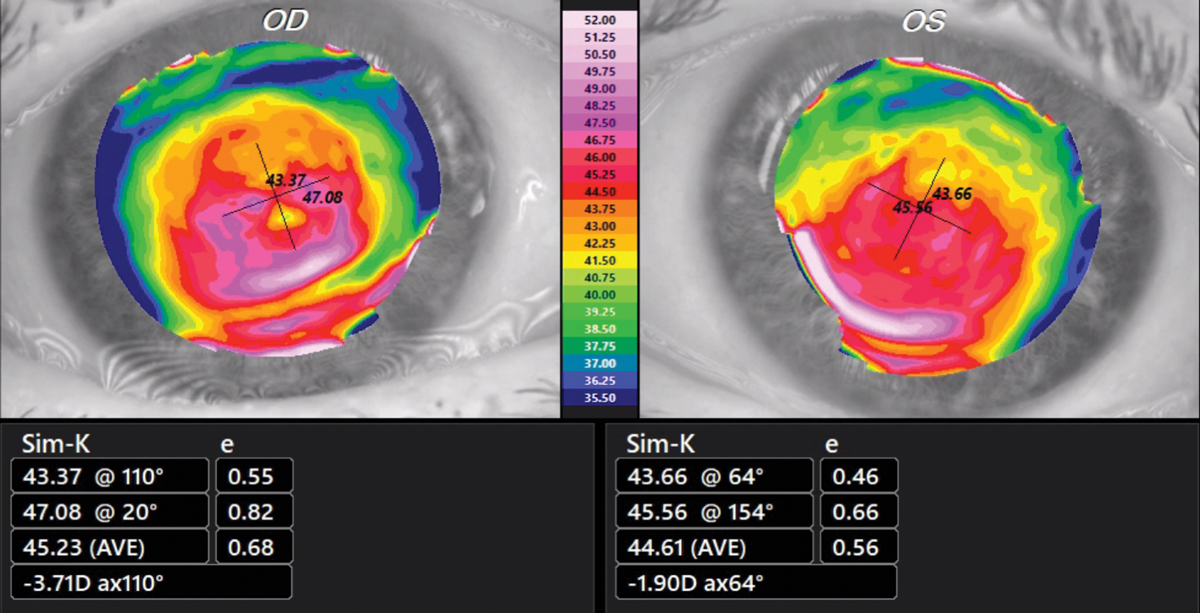

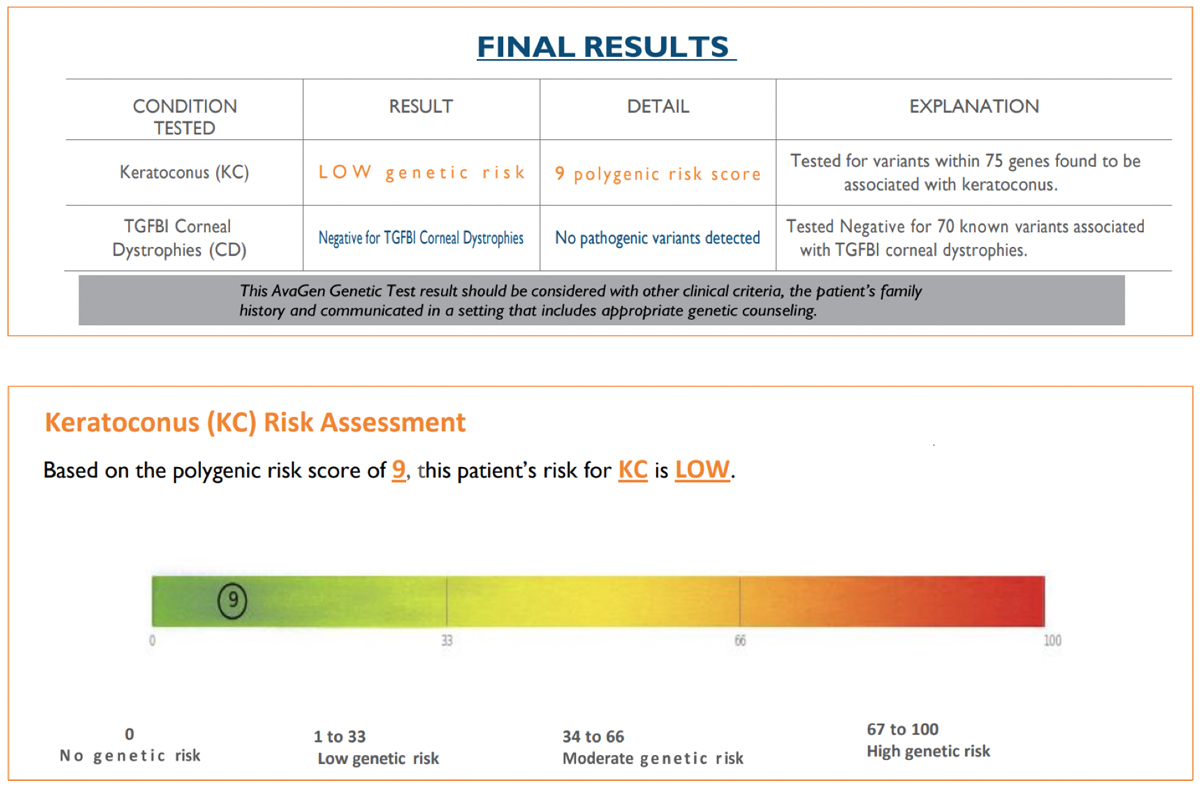

The Test SubjectPatient JL, a 74-year-old Caucasian male with known KCN and a strong family history of KCN, (sister, half-brother, aunt) served as the subject. On 3/2/20, best-spectacle corrected visual acuity was 20/25 OD with +1.75 -5.50x095 and 20/20 OS with +1.25 -3.00x070. Corneas showed an absence of apical scarring, Vogt’s striae and Fleischer rings. Tangential corneal topographies showed a globus-type cone (Figure 1). First SubmissionBuccal swab samples were collected on 4/24/20 and received by the lab on 4/27/20. The test requisition form was completed without disclosing the diagnosis of KCN and family history of KCN. The AvaGen report was generated on 8/11/21 with a PRS of 9, meaning the patient’s risk for KCN was low (Figure 2). Genes with KCN-associated variants were ZEBI and MYLK. The low risk score did not make sense to me, so I submitted a repeat sample.

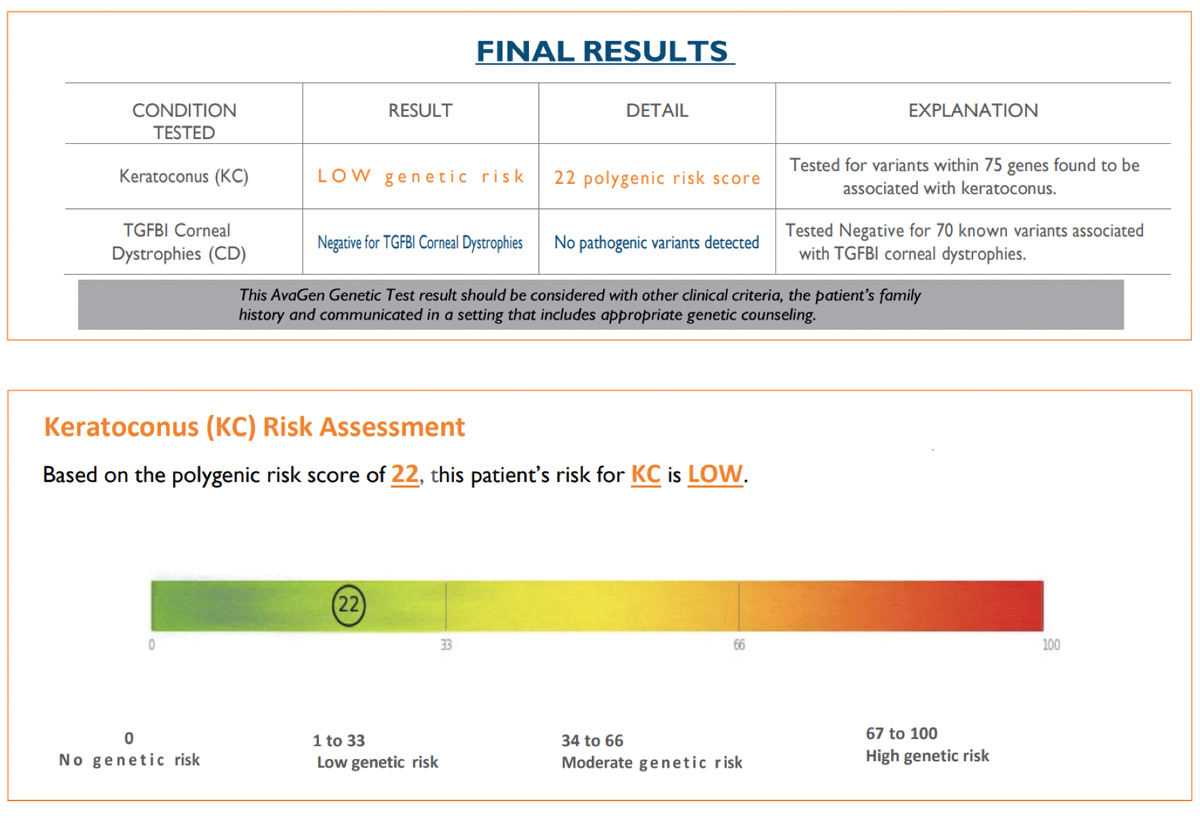

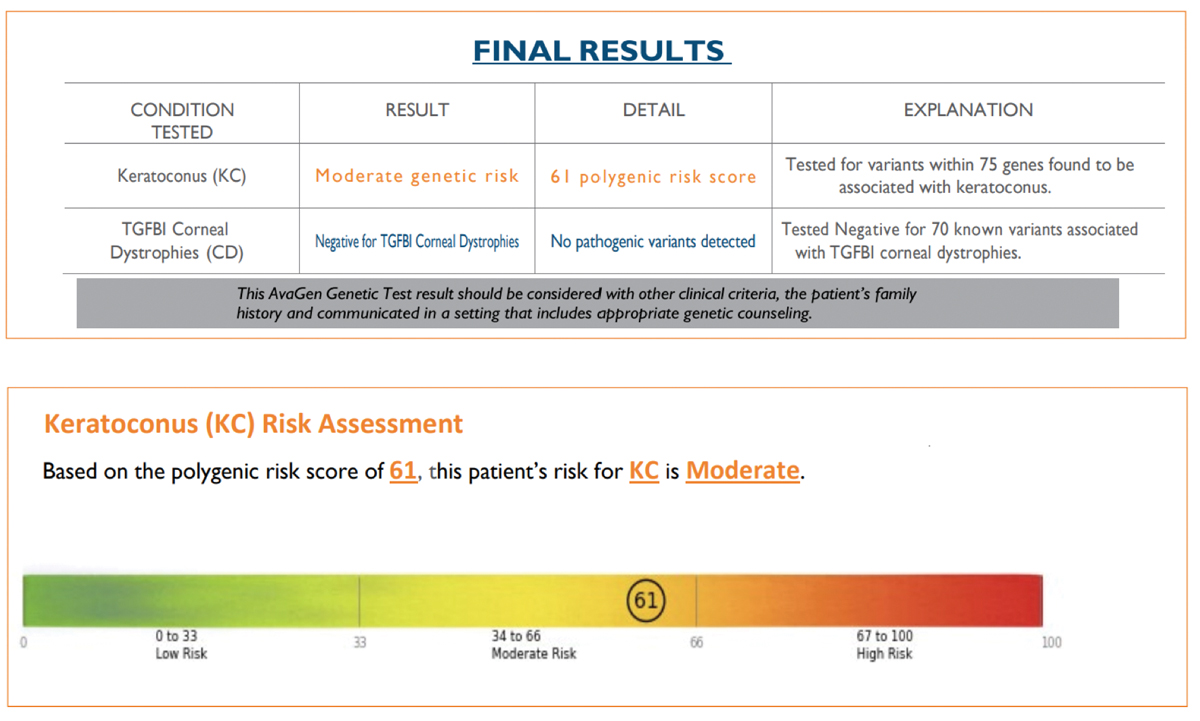

Second SubmissionBuccal swab samples were again collected from JL on 9/12/21 and received by the lab on 9/16/21. The test requisition form was submitted using an alias without disclosing a known diagnosis of KCN or the family history of KCN. The AvaGen report was generated on 9/26/21 with a risk score of 22, indicating the patient’s risk for KCN was low (Figure 3). Genes with KCN-associated variants were MYLK, AGBLI and ZEBI. The different risk score and additional variant for the same patient was unexpected, so I submitted yet another repeat sample. Third SubmissionBuccal swab samples were again collected from JL on 10/10/21 and received by the lab on 10/15/21. The test requisition form was submitted under yet another alias, this time disclosing a known diagnosis of KCN but not disclosing the family history of KCN. The AvaGen report was generated on 11/10/21 with a PRS of 61 categorizing the patient’s risk for KCN as moderate (Figure 4). Genes with KCN-associated variants were COL2A1, COL4A1, COL5A1, COL6A1 and LTBP2.

Same Patient DNA, Three Different ResultsTo recap, the PRS of the first submission came back as 9, the second submission came back as 22 and the last submission came back as 61. The first two submissions identified genes with KCN-associated variants as ZEBI and MYLK, although the second submission also picked up AGBLI. The third submission did not detect ZEBI, MYLK or AGBLI, while finding five other genes with KCN-associated variants that were not detected in the first two submissions. The inconsistency of the results is concerning. As the subject’s DNA composition remained the same, some as-yet-unknown extrinsic factor contributed to the findings. What effect could inaccurate or inconsistent genetic results have on patient health and safety? Some doctors are reportedly using AvaGen to tip the scales in deciding whether to perform corneal surgery. These are non-trivial decisions. What if a patient undergoes corneal crosslinking unnecessarily based on genetic test results that mistakenly suggest elevated risk for KCN? What if a 25-year-old myope gets a PRS of 9 (like the first submission), contributing to a surgeon’s decision to perform LASIK, yet the patient subsequently develops keratectasia? Perhaps my findings are an anomaly. I encourage other practitioners to share their experience. While my primary concern is with the inconsistent results for samples submitted from the same patient, clinicians also need to know how different demographic and clinical data affect the PRS calculation for AvaGen. The specific details of the methods were not available to AvaGen providers at the time that I inquired. However, I learned that Avellino is developing a white paper to shed light on this calculation.8 Eyecare professionals need to know the clinical validity and clinical utility of the AvaGen testing and the PRS algorithm. Clinical validity refers to how well the genetic variants being analyzed relate to the risk of developing KCN. Think of clinical validity as including sensitivity, specificity and predictive value.9 Presently, there is no federal oversight of the clinical validity of most genetic tests.10 Clinical utility refers to whether the test can help with diagnosis, treatment, management or prevention of KCN. Neither the FDA nor CMS has issued formal plans to regulate the clinical utility of genetic tests.10 Due to the relative newness of clinical genomics, oversight of clinical validity and clinical utility is evolving. While precision medicine is welcome in KCN cases, the clinical validity and utility of testing like AvaGen needs greater characterization by independent clinicians and researchers, laboratories and other stakeholders. My reported findings are limited because they come from a single patient. They cannot necessarily be generalized. Yet the inconsistency of the AvaGen results also cannot be discounted. Their mere existence should give clinicians pause to consider if it is an isolated aberration or suggestive of a need for refinement in the test. Dr. Chou practices at ReVision Optometry, a referral clinic for keratoconus and scleral lenses in San Diego. He reported the first US case of Intacs for keratoconus, wrote the chapter on keratoconus in Ocular Therapeutics Handbook, and is a past recipient of the National Keratoconus Foundation’s Top Doctor award.

|

Potential Benefits

KCN is a highly prevalent genetic disease, and early diagnosis and management is essential to preserve vision, says Dr. Barnett. “With early detection, we can recommend corneal stabilization with CXL to avoid corneal transplantation,” she says.

An early diagnosis can also improve the quality of life and independence for individuals with the condition, in addition to lessening the disease’s lifetime economic burden, Dr. Barnett explains. Genetic testing can provide reassurance and hope to individuals with KCN and their families, which will improve the vision-related quality of life over a person’s lifetime, according to her.

“The wonderful aspect of genetic testing is increasing awareness of KCN,” Dr. Barnett says. “KCN is a highly prevalent condition and should be ruled out on every single eye examination, just like dry eye disease and myopia.”

Dr. Bronner, who isn’t using the AvaGen test, believes this tool does have a role, although in its current form, a relatively narrow one.

The benefits he sees in genetic testing include enhanced vigilance in screening, which could allow the disease to be caught earlier—and subsequently halted with CXL—and reduced tolerance for otherwise borderline refractive surgery cases. “As with many diseases, the earlier you catch KCN, the better off the patient will be,” Dr. Bronner explains.

Although genetic testing does not diagnose the condition, a positive genetic risk profile can be used to recommend more frequent screenings with Scheimpflug imaging that can be used to diagnose the disease, at which point timely intervention can be offered, he adds.

Since KCN is known to have a genetic component, many patients who are diagnosed with the condition want to know if they can pass it onto their children or whether other family members could be at risk, says Stephanie Woo, OD, of Las Vegas.

Dr. Woo will recommend genetic testing if a patient is at high risk for KCN, with indicators such as large changes in refractive error, large amounts of cylinder and visual acuity less than 20/20 with correction. When she does perform genetic testing, Dr. Woo will do it along with other diagnostic tests, such as topography, tomography and pachymetry.

“This helps us determine the genetic risk factor and develop an appropriate treatment plan for that specific patient,” Dr. Woo says.

Additionally, the test can be used on children. Since younger patients tend to progress more rapidly, it is important to examine and treat children of individuals with KCN, Dr. Barnett suggests. “A person’s genes don’t change over a lifetime,” she says. “Since genetic testing is easy to perform and isn’t painful, it is an option for adults and children alike.”

This example hit close to home for Dr. Brujic, since one of the first AvaGen tests he administered at his practice was on his young daughter.

“We were going to put her in orthokeratology (ortho-K), but she had suspiciously thin corneas. They looked normal and had a normal curvature and shape, but they were very thin to the point where I wanted to rule this out before we proceeded. We don’t have a family history of KCN, but it was such a bizarre clinical finding,” Dr. Brujic explains.

After running the test and receiving a zero-risk result, Dr. Brujic said he felt a higher sense of security putting his daughter on an ortho-K treatment regimen. “The last thing I’d want is to put her or another patient at risk by placing them in ortho-K lenses that could lead to quicker KCN progression,” he says.

One Piece of the Puzzle

It is important to use genetic testing as one piece of the clinical decision-making process, along with clinical tests, including corneal topography, corneal tomography, OCT, wavefront analysis, optical response analyzer, keratometry and visual acuity, Dr. Barnett says. Other considerations include age, ethnicity, allergies, asthma, atopy, sleep apnea, collagen vascular diseases, diabetes, mitral valve prolapse and Down syndrome, she adds.

Even if a practice doesn’t have advanced technology, evaluating for risk factors such as eye rubbing, the quality of vision on refraction, frequent changes in glasses or contact lens prescription, retinoscopy and mires on keratometry can be used, Dr. Barnett suggests.

Like most medical diagnoses, one test in isolation is not sufficient, echoes Dr. Woo. “Just because someone is at high risk on their genetic test does not mean that they have KCN,” she says. Other testing, such as topography, refraction and a slit lamp exam, will be needed.

This test shouldn’t be used alone to recommend CXL, which requires a diagnosis of progressive keratectasia, Dr. Bronner notes. With genetic profiling in diseases that aren’t purely genetic, be careful in how you interpret and present the data to patients. Genetic testing alone won’t determine the diagnosis of KCN, but if a patient scores in the low-risk category, a practitioner may adjust their treatment plan, Dr. Woo adds.

For instance, if a child has a high amount of astigmatism, normal topography and low-risk results from a genetic test, consider repeating their refraction, topography and slit lamp exam annually or every six months. If that same patient scores high on the genetic risk scale, consider seeing them more frequently to monitor for KCN, she suggests.

Q&A With AvellinoHere, Avellino representatives Yelena Bykhovskaya, principal scientist, and Joe Boyd, global head of sales and marketing, offer responses about their test’s accuracy, benefits and the possible reasons why a clinician might receive varying results from the same patient. What are the benefits of genetic testing for KCN for patients and practitioners? Early diagnosis of keratoconus (KCN) is critical to successful medical management of the disease to preserve vision—a goal shared by both patients and practitioners. Genetic testing, including AvaGen (Avellino), helps eyecare professionals (ECPs) uncover a potential risk for KCN even prior to a diagnosis suspected by preliminary indications revealed via slit lamp exam, keratometry, topography or tomography. Further, a genetic diagnosis of KCN informs patients and families of a risk profile, which allows for even earlier medical intervention to protect against vision loss. AvaGen provides ECPs a tool to test patients and detect corneal conditions earlier, subsequently allowing treatment to begin sooner and counter the course of the disease. For LASIK and other corneal surgical procedures, genetic testing provides surgeons with additional data points to consider for a patient’s treatment plan by ruling patients in or out for surgery. What is the accuracy rate of the test and what are the scores based on? KCN is a polygenic disease. Avellino developed a proprietary algorithm to determine a risk score (a polygenic risk score, or PRS) based on the genetic testing of a large cohort of available KCN patients and controls collected by the company. The testing process includes sequencing a panel of genes to determine the number of risk and protective variants in the patient. These variants determine the patient’s PRS that fall into a low, moderate or high risk. The clinical sensitivity of AvaGen’s PRS score for KCN is estimated to be 80% in the discovery cohort. Avellino is currently performing a clinical validation of sensitivity in an independently collected large cohort of KCN cases and controls. The clinical sensitivity and specificity of the test may continue to improve as the test numbers increase and as we include more risk genes for KCN in the gene panel. As this is a new technology, are there any current limitations of the testing? Polygenic disease, where several risk genes each contribute to the manifestation, is very different from the category of monogenic diseases, (e.g., corneal dystrophies and retinitis pigmentosa, which are inherited in a Mendelian pattern). Most physicians are quite familiar with monogenic diseases, where the presence of a pathogenic variant in the target gene leads to the disease. The clinical test reports for monogenic diseases are binary “yes or no” results. For polygenic diseases, a PRS is used to determine a patient’s genetic risk profile. The methodologies of polygenic risk are evolving and, while currently there are no clear standards in the field on how this statistical algorithm should be developed or reported, we continuously improve the AvaGen test scoring methods and robustness. In addition to following the latest improvements in PRS algorithm development, Avellino is increasing the size of the cohort of KCN patients (cases) and healthy individuals (controls) in collaboration with various eye clinics. We also look to the published data on genetic association studies in KCN to consider in future gene panels. As more data is gathered over time, will the test offer an even greater predictive value? The human genome has approximately 22,000 genes, and there are thousands whose function is yet undiscovered, thus there is ample opportunity to continue to understand KCN. The current test detects 75 genes; however, published KCN research indicates there may be many more that contribute to genetic risk for this disease. Future iterations of AvaGen may include these additional genes, increasing the test’s predictive value and thus its clinical utility.

If a doctor submits more than one sample from the same patient and gets a different risk score, what could be the cause of this? The AvaGen test was launched in June 2021, with a significant PRS algorithm update in October of the same year. Therefore, depending upon the date of submission, different scores from the same patient are possible. The next generation sequencing methodology used in the AvaGen test has a greater than 92.7% run-to-run concordance. Therefore, multiple testing of the same person’s DNA occasionally results in different calls for some DNA variants. However, since the PRS is based on the combination of multiple variants, in these cases, it may shift a few points but generally will be within the same risk category (low, medium or high). Our laboratory testing results indicate that for a majority of clinical samples, identical PRS scores are calculated for multiple replicates of the same person’s DNA sample. It is important to understand that there is some fluidity with the risk scoring because it is not a single pathogenic mutation analysis, as in monogenic diseases. New knowledge and advancements in the field of polygenic diseases will lead to better risk assessments and understanding of the genes that contribute significantly to the risk. Polygenic conditions are complex, and a PRS should always be used in conjunction with other diagnostic testing, a clinical eye examination, guidance from a qualified doctor and referral to a specialist as appropriate so the patient receives the best possible treatment course. Results should also be considered with other clinical criteria, the patient’s family history and behavioral and environmental contributors. Results of the genetic testing should be communicated in a setting that includes available genetic counseling. Do different demographic and clinical data affect the PRS calculation? Yes. Historic lack of diversity in genomic studies led to limited applicability of the majority of PRS. However, our PRS was developed using a diverse ethnicity cohort. In general, you want a genetic test to work in all ethnic groups. However, different genes or different risk variants may give rise to the same disease in different populations. Thus, when deriving the PRS system, it’s best to have a good distribution of different ethnicities in the discovery cohort so differences in allele frequencies or different risk variants can be adjusted using statistical methodology. In addition, polygenic disease is influenced by environmental and behavioral factors that can trigger activation and progression. What’s the clinical utility of AvaGen testing? KCN is an underdiagnosed disease with sight-threatening consequences. Early detection through genetic testing leads to improved clinical outcomes through early intervention to slow progression. Importantly, a genetic finding of KCN in one patient can lead to even earlier clinical intervention in that patient’s family. |

Gray Areas

Despite genetic testing’s benefits, misperceptions of its role need to be considered, Dr. Bronner points out.

“I’ve heard people describe this test as being able to diagnose future KCN. This is incorrect,” he says. “As with many diseases with a genetic risk, development of KCN is multifactorial, so even people with a ‘high risk’ genetic profile aren’t guaranteed to develop the disease.”

Another caveat: this can lead to unnecessary healthcare expenditures with frequent screening, and most insurance plans don’t pay for truly diagnostic tests for KCN, barring an actual ICD-10 KCN code. So these screening costs are, in most cases, passed on to the patient.

The flip side of this scenario may also hold true. A patient with a first-degree family member with KCN who receives a “low/no risk” result may be saved screening expenses, Dr. Bronner explains.

“The final caution with this test is how it might prevent otherwise good candidates for refractive surgery from proceeding with a desired refractive procedure,” Dr. Bronner says. “If I were the doctor ordering this test, and it came back positive for genetic risk but the patient had no other risk factors for ectasia/KCN, that would shape my recommeandations for LASIK/PRK.”

With that said, in his 15-year career treating thousands of refractive surgery patients, Dr. Bronner had only one patient with no true ectasia risk factors on exam who later developed post-LASIK ectasia.

“Based on my experience alone, I feel this test has more potential to interfere with otherwise safe refractive surgery than it does to prevent unsafe surgery,” he says. On the other hand, for somewhat borderline refractive candidates—especially in those with a family history of KCN—this test could be extremely valuable in shaping firm recommendations against surgery, he adds.

“As with all forms of genetic testing, you have to avoid painting the risk with too broad of strokes,” Dr. Bronner says. “If you use this test, you have to avoid taking the information too far.”

Yet another consideration is the technology’s newness. The test’s predictive value is likely to improve as sample sizes grow.

As with all new technologies, you may get very clear delineated answers in some cases, but you may have additional variables that obscure the clearest path forward in others, Dr. Brujic adds. For individuals in the middle, the test can provide another layer of complexity to the diagnostic algorithm.

For example, if a patient has normal corneas and other diagnostic tests have ruled out KCN but the parents have the condition, ordering the genetic test is clearly of value, Dr. Brujic says. However, if a test is ordered because a patient has certain suspicious corneal topography readings or refractive error measurements, a moderate risk on genetic testing may increase suspicion but still doesn’t clearly indicate KCN.

“With these types of early findings, we are looking for further genetic information to determine how closely we should be monitoring this individual or whether we can let this person go a bit longer without seeing them,” he suggests.

If a patient has a family history of KCN with negative, healthy corneal findings and a low-risk genetic test result, would it be reasonable for the individual to undergo refractive surgery? “Assuming all other clinical findings support refractive surgery, the answer would be yes,” Dr. Brujic says. “That would definitely make me feel more comfortable recommending refractive surgery.”

Another area that requires a measured approach to the test is a patient’s potential reaction to the results, adds Dr. Woo. A patient who scores high on the genetic risk scale might become anxious or develop emotional issues related to the information, she explains.

Final Thoughts

Genetic testing for KCN may offer insight into a patient’s future risk of developing the condition, yet doctors caution not to skip out on the tried-and-true screening tools for a true clinical assessment.

“Genetic testing is a supplemental test in screening for keratectaisa. Scheimpflug corneal imaging does the heavy lifting and is the gold standard for diagnosing the conditions,” Dr. Bronner says. “This modality’s ability to detect subtle patterns in pachymetric profiles, topographies and especially elevation deviations make it extremely useful in the diagnosis of early keratectasias, and careful interpretation of this data will allow avoidance of refractive surgery for at-risk patients as well.”

Adds Dr. Barnett: genetic testing helps identify patients who are at risk of KCN, but similar to many genetic tests, there are undiscovered genes that may contribute to the disease. “As new genes and variants are discovered, genetic testing for KCN will continue to evolve,” she says.

1. Avellino Launches AvaGen Nationwide as First Genetic Test to Quantify Keratoconus Risk and Presence of Corneal Dystrophies. www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210602005304/en/avellino-launches-avagen-nationwide-as-first-genetic-test-to-quantify-keratoconus-risk-and-presence-of-corneal-dystrophies. June 2, 2021 2. Chen S, Li XY, Jin JJ, et al. Genetic screening revealed latent keratoconus in asymptomatic individuals. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 May 31;9:650344 3. McComish BJ, Sahebjada S, Bykhovskaya Y, et al. Association of genetic variation with keratoconus. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020 Feb 1;138(2):174-181. 4. Ferdi AC, et al. Keratoconus natural progression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 11,529 eyes. Ophthalmol. 2019;126(7):935-45. 5. Abu-Amaro KK, Al-Muammar AM, Kondkar A. Genetics of keratoconus, where do we stand? J Ophthalmol. 2014; 2014: 641708. 6. Hardcastle AJ, Liskova P, Hysi PG. A multi-ethnic genome-wide association study implicates collagen matrix integrity and cell differentiation pathways in keratoconus. Communications Biology 4, 266 (2021). 7. Woodward MA, Blachley TS, Stein JD. The association between sociodemographic factors, common systemic diseases, and keratoconus: an analysis of a nationwide healthcare claims database. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(3):457-65. |