|

A 64-year-old female presented to my clinic for an anterior segment follow-up with minimal complaints. The patient reported that she had seen her retina specialist the day before and he told her she had some “very rare” changes to her cornea. I looked back through previous exams and everything had been unremarkable. The patient had no relevant medical history, although her ocular history was significant, as the patient had primary open-angle glaucoma in both eyes, moderate stage. The patient also had a history of intolerance to Travatan (travaprost, Novartis) and Rhopressa (netarsudil, Aerie) due to medicamentosa. Her current drop regimen was Rocklatan (netarsudil & latanoprost, Aerie). The patient was also being followed for blepharitis and dry eyes.

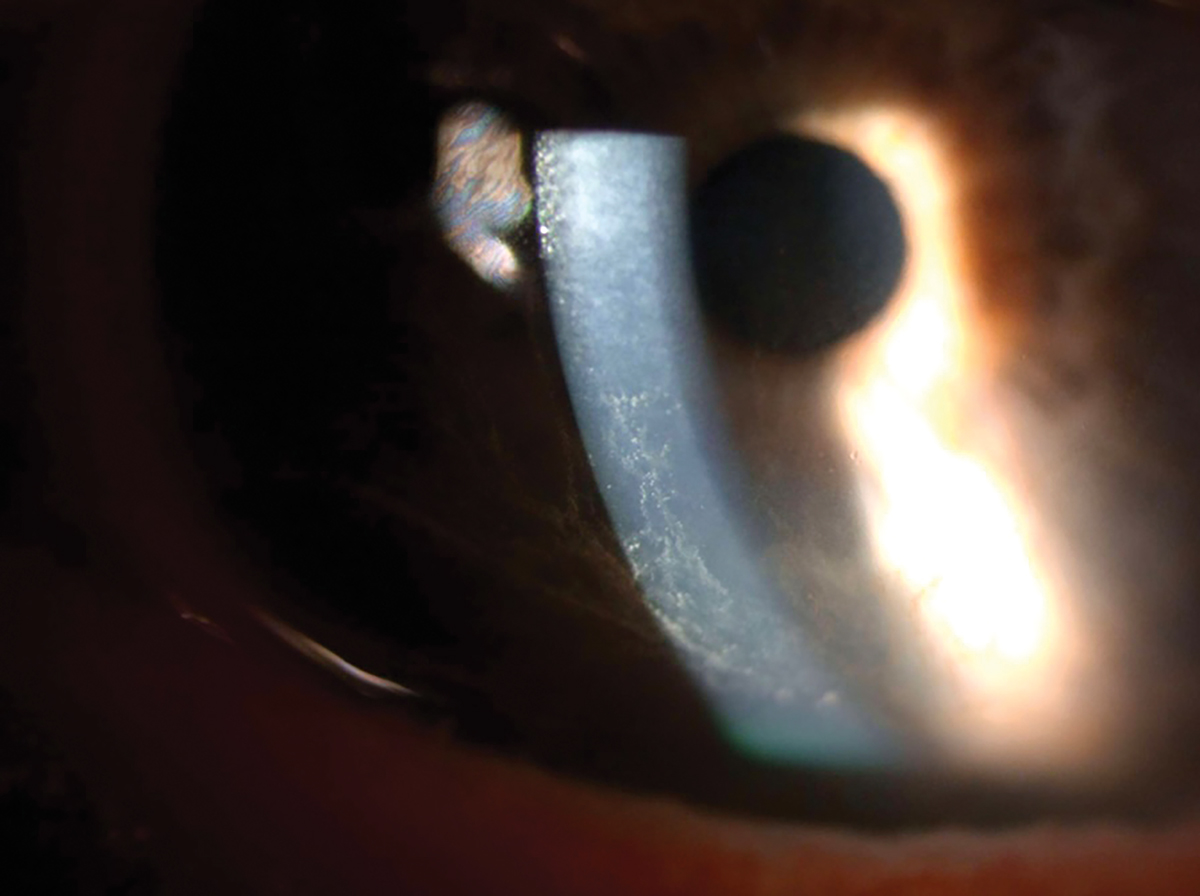

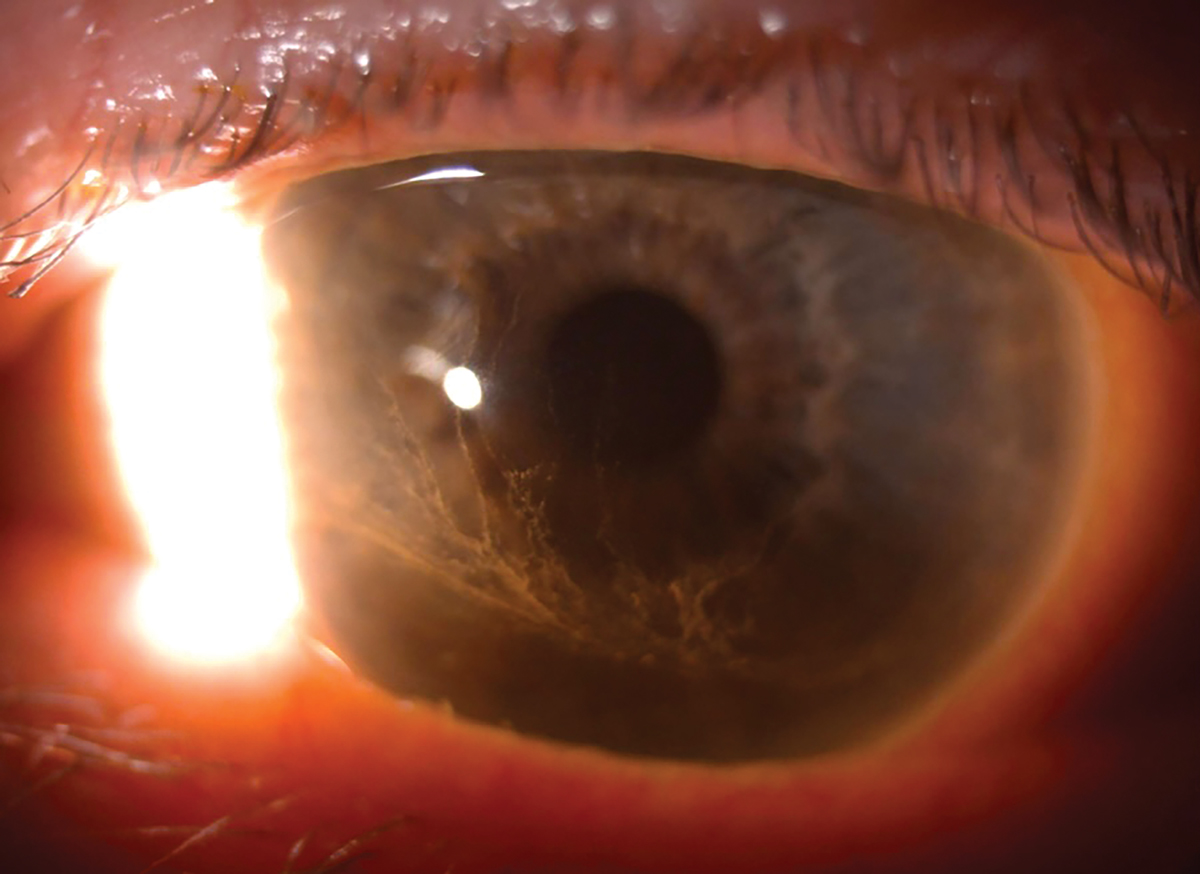

Her entering acuity OD and with correction was 20/25+2 20/25+2 OS. Her intraocular pressure taken with applanation was 12mm Hg OD and 14mm Hg OS. The slit lamp exam revealed meibomian gland dysfunction of the right and left upper and lower lids. Mild injection of the bulbar conjunctiva was seen OU. The cornea revealed a bilateral whorl-like pattern of powdery, whitish yellow-brown epithelial defects OS more than OD located in the inferocentral cornea. The whorl pattern swirled outward but did not cross onto the limbus OU. The iris had regular, absent ruff with some pigmented dots, and the lens had nuclear sclerosis OU.

This patient had been closely followed for a year by both myself and a glaucoma specialist in our practice. Over the last year and half, the patient was on Rocklatan (1,1) and no corneal abnormalities were observed by either provider. At this visit, the patient was diagnosed with corneal verticillata, known otherwise as whorl keratopathy or vortex keratopathy.

|

|

Corneal epithelial deposits on the inferior half of the cornea. Click image to enlarge. |

Vortex Keratopathy

There are numerous medications that can cause corneal epithelial changes that are often characterized by deposits that may present as vortex keratopathy, diffuse corneal haze, punctate keratopathy and/or crystalline precipitates. Literature reveals most drug-induced corneal epithelial changes are drug-specific. These drugs vary in differing pharmacologic actions and most are amphiphilic and cationic (hydrophobic ring structures on the molecule and a hydrophilic side chain with a charged cationic amine group). The reason they produce a vortex or whorl-like pattern is because of the accumulation of lipids or iodine.1 The vortex pattern of corneal deposits is caused by normal epithelial turnover and migration.

Associated Drug Risk

There are some drugs, including several antibiotics, that produce corneal epithelial changes; however, they do not cause a whorl-like keratopathy. Instead, they can cause corneal toxicity, conjunctival pseudomembrane and delays in corneal reepithelization.

• Cationic amphiphilic drugs. Amiodarone is the most widely studied drug that causes corneal epithelial changes. In almost all patients, it causes bilateral vortex keratopathy, described as a pattern of ocher to golden corneal deposits in a vortex configuration. These do not often interfere with visual acuity, although patients do report eyelid irritation, photophobia and halos. The onset of corneal changes becomes apparent as soon as two weeks after beginning treatment, but symptoms more commonly appear between one and four months.1 Deposits occur in 98% of patients on approximately 200-300mg/day and 99% of patients on 200-1200mg five days a week.2 Around 50% to 60% of cases result in keratopathy or lens opacities, causing drug discontinuation or modification.3

For aminoquinolines, including antimalarials (amodiaquine, chloroquine, mepacrine/quinacrine and hydroxychloroquine), the initial onset of presentation is similar to amiodarone, beginning after two to three weeks or after a few months of drug use.4 Unlike the retinopathy caused by these agents, the keratopathy reverses with cessation of treatment.4

Chloropromazine, an antipsychotic medication, has been known to cause vortex-like corneal deposits when prescribed at a higher or lower dosage long-term. However, these deposits more typically occur in the stroma or the endothelium.1

• Antineoplastic agents (cationic/amphiphilic). Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator used for breast cancer treatment and prophylaxis. It has been reported to induce subepithelial deposits, vortex keratopathy and linear opacities even at very low dosages for prophylaxis (20mg/day) in around 11% of patients.5 These corneal changes are reversible when the medication is discontinued but, as with hydroxychloroquine, the retinal changes may not be reversible.

• Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Ibuprofen, naproxen and indomethacin have all been described to cause intracellular deposits in the epithelium. These deposits appear quickly when the dosage is high (for example, 1200mg/day of ibuprofen) and resolve rapidly. NSAID cases have been reported in a small series of patients and the majority are in patients on prolonged indomethacin treatment.6

• Antibiotics. Aminoglycosides typically cause superficial punctate lesions, although subconjunctival gentamicin can produce vortex keratopathy.7

The macrolide clarithromycin, which is cationic but not amphilic, has been shown in single case reports to produce subepithelial corneal deposits. This is true of both oral and topical versions of the drug.1

The specific fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin is associated with white, crystalline corneal epithelial deposits that are precipitates of the drug.8 If the epithelium is compromised, vision can decrease, but the deposits resolve within two weeks to a few months once the drug is discontinued.9

• Glaucoma medications. Rhopressa, a combination rho-kinase inhibitor used in the Rocket clinical trials, showed corneal verticillata (vortex keratopathy) after one month in about 21% of patients given Rhopressa once a day. The brownish gray subepithelial deposits radiate in the central cornea in the whorl pattern. In the follow-up study on Rhopressa, 45 patients who had corneal verticillata experienced resolution after discontinuation, and three patients did not. These corneal changes did not cause meaningful changes to visual function.10 As a reminder, these changes will also be seen with Rocklatan because of the Rhopressa component.

There are many other categories of drugs that can cause corneal epithelial changes, including but not limited to gold salts, antineoplastic agents and antibody-drug conjugates.

|

|

Corneal epithelial deposits encroaching the visual axis, although not visually significant. Click image to enlarge. |

Endogenous Causes

There are a number of endogenous causes of corneal epithelial changes, one being Fabry disease. With this condition, these patients are usually already diagnosed before any corneal changes are identified. A carrier of the disease, though, may see vortex keratopathy as the first indication.1 Similarly, clinicians can identify paraproteinemia on slit lamp exams due to corneal epithelial changes before the systemic disease has been diagnosed.1 Additionally, a low incidence of gout can cause crystalline corneal deposits.

Superficial corneal dystrophies, such as Meesmann corneal dystrophy and Lisch corneal dystrophy, can present with a vortex pattern of corneal deposits. In Meesmann, the corneal deposits are central and peripheral and caused by intraepithelial cysts which appear during infancy. Lisch corneal dystrophy presents with feather-shaped opacities and microcysts arranged in a band or vortex pattern.11

Management

In most cases, it is not recommended to alter a treatment regimen due to drug-induced epithelial corneal changes on the basis of keratopathy since the findings are usually benign. Many cases are asymptomatic, and most do not result in decreased visual acuity. It should be noted that this is not the same treatment and management protocol as medications that result in retinal toxicities.

1. Raizman MB, Hamrah P, Holland EJ, et al. Drug-induced corneal epithelial changes. Surv Ophthalmol. 2017;62(3):286-301. 2. Ghosh M, McCulloch C. Amiodarone-induced ultrastructural changes in human eyes. Can J Ophthalmol. 1984;19(4):178-86. 3. Mäntyjärvi M, Tuppurainen K, Ikäheimo K. Ocular side effects of amiodarone. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42(4):360-6. 4. Dosso A, Rungger-Brändle E. In vivo confocal microscopy in hydroxychloroquine-induced keratopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;245(2):318-20. 5. Nayfield SG, Gorin MB. Tamoxifen-associated eye disease a review. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(3):1018-26. 6. Fitt A, Dayan M, Gillie RF. Vortex keratopathy associated with ibuprofen therapy. Eye. 1996;10(1):145-6. 7. Hollander DA, Aldave AJ. Drug-induced corneal complications. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004;15(6):541-8. 8. Fraunfelder FW. Corneal toxicity from topical ocular and systemic medications. Cornea. 2006;25(10):1133-8. 9. Zawar SV, Mahadik S. Corneal deposit after topical ciprofloxacin as postoperative medication after cataract surgery. Can J Ophthalmol. 2014;49(4):392-4. 10. BusinessWire. Aerie Pharmaceuticals announces FDA advisory committee vote in favor of Rhopressa (netarsudil ophthalmic solution) 0.02%. October 13, 2017. 11. Klintworth GK. Corneal dystrophies. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:7. |