|

A 60-year-old male presented complaining of decreased vision of his left eye in his scleral contact lens. He reported that his vision was hazier than usual even wearing glasses. His ocular history was significant for a failed corneal transplant OD resulting in light perception vision and a penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) OS one year prior. He had a history of wearing a custom scleral lens OS. His drop regimen at the time was Durezol (difluprednate) every other day OD, Pred Forte (prednisolone) and Celluvisc (Refresh) OS.

Entering corrected acuity was 20/600 OS, pinhole to 20/400, and IOP was 16mm Hg. On exam, his palpebral conjunctiva was 2+ injected; he had slight edema on his PKP near a broken suture at 10 o’clock with a small epithelial defect and a small stromal infiltrate. The anterior chamber had a grade 1 cell, his pupil was round and reactive and he had grade 1 nuclear sclerosis.

Diagnosis

The patient was diagnosed with a broken PKP suture OS with a small corneal infiltrate. The suture was removed in-office and the patient was instructed to discontinue lens wear. An assumption was made that the keratitis was likely bacterial in origin due to his contact lens use. He was instructed to continue Pred Forte BID and start moxifloxacin every waking hour.

He returned after a long weekend with his vision and IOP unchanged. The edema had improved, the epithelial defect was resolving and the small stromal infiltrate was receding. He was instructed to switch his moxifloxacin every two hours.

Five days later he returned and reported significant improvement. Entering acuity with glasses correction was 20/300, IOP was 19mm Hg, trace edema was seen, the epithelial defect had resolved and the infiltrate was gone. The patient was tapered to moxifloxacin four times a day.

One week later, vision had improved to 20/150 with correction, IOP remained normal, the PKP was clear, no edema was present and a small scar at 10 o’clock had formed. The patient was told to continue moxifloxacin for four more days and then discontinue. He was told he could restart lens wear in one week. At his two-week follow-up visit, his vision was back to its baseline of 20/70 in his scleral contact lens.

What's the Stitch?

In this case, the patient was post-PKP; however, a suture complication can occur days to years after any suture placement, whether due to cataract extraction, laceration repair, glaucoma surgery and more.

When a patient has a suture in their eye, the possibility of a suture-related problem is present. As surgeons, ophthalmologists must make the decision of which type of suture material to use (nylon vs. Mersilene), which technique to use (continuous vs. interrupted) and when to remove the suture. The primary purpose of the suture placement at the time of surgery is proper apposition of the wound edges and aiding in the healing process.1

As optometrists, we play a vital role in recognizing the proper material, technique and use of these sutures at the same time as managing any complications they cause. Corneal sutures can lead to eye irritation, inflammation and increased risk of infection. Suture-related problems can involve excess tightness, loosening, breakage, infiltrates, giant papillary conjunctivitis, neovascularization and more.

The quickest way to access a suture is using topical sodium fluorescein (NaFl). If the suture is appropriately covered by epithelium, there should not be staining of the NaFl under blue light. If NaFl staining is seen, a thorough exploration for a broken, loose or eroded suture must be conducted.

Complications

There are different kinds of suture complications, as detailed below:

Excessive tightness. Tightening can occur after a suture is placed and ultimately lead to irregular astigmatism. This can be followed by retinoscopy, refraction and corneal topography. Often the decision to remove a suture is made to decrease induced astigmatism.

Suture loosening. Wound contraction is the usual cause of any loosened sutures, suture breaking, biodegradation of the suture material or suture cheese wiring with time. In a five-year retrospective PKP study in Cornea, the occurrence of loose sutures that would cause imminent wound separation needing surgical repair was 8.3%.

Broken, continuous suture. This does not aid in controlling wound stability and is why it has to be removed as soon as possible. Symptoms of postoperative suture breakage may be one or more of the following: foreign body sensation, irritation, redness, photophobia, epiphora and visual acuity alteration. Signs of postoperative suture breakage consist of the suture end which may be visible, discharge, injection, cells and flare, mucus filaments, conjunctival hyperemia, wound leak and more.

An infectious abscess. These are usually localized around or near a broken, loose or exposed suture. Patients often complain of foreign body sensations, irritation, redness, photophobia, epiphora and visual changes. In the same five-year study, the occurrence of suture erosions was 10.8%, and in these cases, fluorescein-stained epithelial defects over one or more sutures were seen. Some patients were symptomatic while some were asymptomatic. Infectious keratitis, which is an ulcerative epithelial defect with stromal infiltrate, was observed to be 3.3% when adjacent to a broken or loose suture. Almost all cases presented with a hypopyon in the anterior chamber. These patients complained of foreign body sensations, discomfort and visual symptoms.

|

|

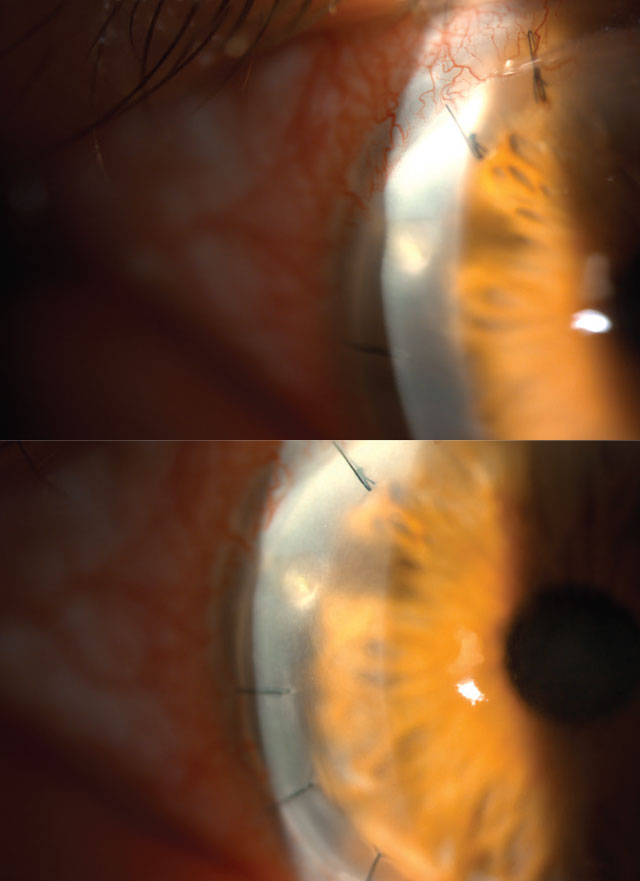

An example of a suture abscess, localized near the suture. Click image to enlarge. |

Noninfectious suture infiltrates. These present as small, non-progressive subepithelial suture infiltrates and were noted to be 0.4%. Subepithelial, suture-related immune infiltrates are common at the entry into the corneal stroma and often present in the early postoperative period. They can be seen on either side of the PKP; however, they are more often seen in the recipient’s cornea. A small portion of these patients had mild foreign body sensations, while the majority were asymptomatic with no visual symptoms, and the complications were observed on a routine follow-up. When cultures were performed on this population they were often inconclusive.2

|

|

Infectious keratitis, resultant of an ulcerative epithelial defect. Click image to enlarge. |

Giant papillary conjunctivitis. This condition is rare; however, it can be caused by exposed knots or broken suture due to a corneal or scleral suture. Often surgeons can rotate the suture so the knot is no longer exposed.

Vascularization. This effect can be seen along suture tracks, indicating that the wound is adequately healed in that area and the suture could be removed safely. It is important to remember that vascularized sutures are also at a high risk of loosening and can increase the risk of graft rejection.

Management

The first step is checking the suture’s integrity and ruling out wound dehiscence and/or identifying an infection. There is no consensus regarding suture removal timing for adults, and often different approaches are used based on surgeon experience.

Non-pharmacological intervention of a loose or broken suture should be exercised with caution. Sterile instruments must be used, and the wound should be checked for leakage after removal. Povidone-iodine solutions are used prior to removal and a topical anesthetic may be necessary to aid in the removal. Prophylactic broad-spectrum topical antibiotic drops are often given until the epithelial defect is closed after removal, especially in cases where there is a likelihood of infection.

Prevention of suture-related complications is related to frequent monitoring and timely intervention. It is important to reiterate to patients the most common signs and symptoms so prompt care can be given.

1. Pagano L, Shah H, Al Ibrahim O, et al. Update on suture techniques in corneal transplantation: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2022;11(4):1078. 2. Christo CG, van Rooij J, Geerards AJ, et al. Suture-related complications following keratoplasty: a five-year retrospective study. Cornea. 2001;20(8):816-9. 3. Henry CR, Flynn HW Jr., Miller D, et al. Delayed-onset endophthalmitis associated with corneal suture infections. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2013;3(1):51. |