Blepharitis is one of the most frequently observed conditions among eye care practitioners, yet remains largely misunderstood. The confusion stems from the fact that the ophthalmic community has yet to determine a standard treatment and universal classification system for the disease. Reports show that up to 47% of patients seen by optometrists in clinical practice show symptoms consistent with blepharitis, and 79% of the general population has experienced at least one symptom of blepharitis in the last 12 months.1 In addition, meibomian gland dysfunction—a common occurrence with chronic blepharitis—affects nearly 40% of routine eye care patients and 50% of contact lens wearers.2,3 Despite this high prevalence, there are no well-controlled clinical trials that support FDA approval for topical agents of either anterior or posterior blepharitis, which presents a frustrating conundrum for eye doctors and the patients they treat.

Blepharitis is one of the most frequently observed conditions among eye care practitioners, yet remains largely misunderstood. The confusion stems from the fact that the ophthalmic community has yet to determine a standard treatment and universal classification system for the disease. Reports show that up to 47% of patients seen by optometrists in clinical practice show symptoms consistent with blepharitis, and 79% of the general population has experienced at least one symptom of blepharitis in the last 12 months.1 In addition, meibomian gland dysfunction—a common occurrence with chronic blepharitis—affects nearly 40% of routine eye care patients and 50% of contact lens wearers.2,3 Despite this high prevalence, there are no well-controlled clinical trials that support FDA approval for topical agents of either anterior or posterior blepharitis, which presents a frustrating conundrum for eye doctors and the patients they treat.

A History Lesson

A History Lesson

The history and evolution of the treatment of blepharitis is surprisingly lengthy. The first mention of what today is referred to as blepharitis dates back to the 19th century; at the time, similar symptoms were referred to as conjunctivitis meibominae and meibomian seborrhea.1

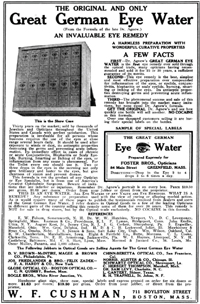

In 1908, The Optical Review recommended the use of Great German Eye Water—an antiseptic that advertised itself as “the most effective preparation ever compounded for blepharitis,” and even boasted the absence of cocaine as an ingredient in its marketing efforts.4 Several years later, in 1946, Phillips Thygeson, M.D., described blepharitis as “a chronic inflammation of the lid border,” and categorized it into two general types: squamous and ulcerative. Riding on the cusp of a new antibiotic age, Thygeson used a combination of antibiotic and hygienic therapy to treat blepharitis, which became the standard treatment for the next few decades.5 As Thygeson associated certain types of blepharitis with an abnormal Staphylococcus colonization, he recommended a specialized treatment of topical penicillin along with lid scrubs.6 In 1982, James McCulley, M.D., structured a non-infectious etiology for blepharitis and organized the condition into multiple classes: seborrheic, meibomianitis, staphylococcal and mixed seborrheic-staphyloccoal.7 More recently, in 2004, William Mathers, M.D., and Dongseok Choi, Ph.D. acknowledged the confusing similarities between dry eye and blepharitis and created a physiological classification tree for both.8 In 2006, Ora, Inc., of Andover, Mass., used anatomical and structural classifications to develop the Ora Lid Margin Disease Digital Image Grading System for blepharitis and meibomitis. These standardized, photo-validated scales have been used in multiple recent studies to evaluate therapeutics for the treatment of blepharitis.9-11

Connecting the Symptoms

Blepharitis is an inflammation of the eyelid margin, which includes the eyelashes and associated meibomian glands. Signs and symptoms of blepharitis can include swelling, scaling and/or crusting of the eyelids, redness of the lid margins, bulbar and palpebral hyperemia, gritty eyes and itchy eyelids, Because blepharitis often coexists with dry eye and meibomian gland dysfunction, there is significant overlap in the signs and symptoms of diseases. In fact, dryness and irritation are the most frequently reported symptoms in both blepharitis and dry eye patients.1,12

The close proximity of ocular structures often leads to shared signs and symptoms of lid margin diseases. For example, an inflamed eyelid can lead to a plugged meibomian gland. Meibomian gland dysfunction directly impacts the tear film, facilitating the loss of the lipid barrier, which, in turn, accelerates evaporative dry eye.13 Meibum, a secretion that forms the top layer of the tear film and prevents evaporative tear loss, is brought directly to the tear film at the eye’s lid margin by the meibomian glands.14 If these glands are either partially or completely blocked by obstructions such as desquamated epithelial cells, stagnation or infection can occur, impeding the production of healthy meibum.3

Multiple lid structures, like the meibomian glands, should therefore be evaluated as part of a thorough eyelid examination in order to accurately diagnose the lid margin disease in question.

Treating the Disease

Evaluating drug treatments for blepharitis has become a priority in the last decade, with several studies emerging in support of a combined antibiotic and steroid therapy. The most common drugs used in these studies are antibiotics—azithromycin, tobramycin—and the glucocorticoid dexamethasone. Recent studies are evaluating the effectiveness of these drugs in targeting possible bacterial overgrowth, altering lipid composition in the meibomian glands and rapidly reducing inflammation associated with blepharitis. One such study used the Ora Lid Margin Disease Digital Image Grading System to compare the clinical efficacy and safety of a tobramycin/dexamethasone ophthalmic suspension—TobraDex ST (tobramycin and dexamethasone, Alcon) with AzaSite (azithromycin 1%, Inspire Pharmaceuticals)—for moderate to severe acute blepharitis. Results showed that Tobradex ST provides faster sign and symptom control and relief for moderate to severe acute blepharitis/blepharoconjunctivitis as compared toAzaSite.9-11 Tobradex ST is a change in formulation from the original combination of tobramycin and dexamethasone (Tobradex, Alcon), constituted by a decrease in the amount of dexamethasone to 0.05% as well as the addition of the retention-enhancing agent xanthan gum. This reformulation accentuates the anti-inflammatory mechanism of the steroid through the addition of xanthan gum which increases therapeutic contact time.

Up for the Challenge

While blepharitis continues to present several challenges, the introduction and accessibility of new medications is rising. Growing awareness of the prevalence of this disease, particularly in the last decade, has led the eye care community to prioritize research into consensual etiologies and effective therapeutic treatments.

1. Lemp MA, Nichols KK. Blepharitis in the United States 2009: a survey-based perspective on prevalence and treatment. Ocul Surf. 2009 Apr;7(2 Suppl):S1-S14.

2. Hom MM, Martinson JR, Knapp LL, Paugh JR. Prevalence of meibomian gland dysfunction. Optom Vis Sci. 1990 Sep:67(9)710-2.

3. Henriquez AS, Korb DR. Meibomian glands and contact lens wear. Br J Ophthalmol. 1981 Feb;65(2):108-11.

4. The Original and Only Great German Eye Water. The Optical Review: Devoted to Optometrists and Opticians. 1908 Jun;2(2):15.

5. Thygeson P. Etiology and treatment of blepharitis; a study in military personnel. Arch Ophthal. 1946 Oct;36(4):445-77.

6. McCulley JP, Shine WE. Changing concepts in the diagnosis and management of blepharitis. Cornea. 2000 Sep;19(5):650-8.

7. McCulley JP, Dougherty JM, Deneau DG. Classification of chronic blepharitis. Ophthalmology. 1982 Oct;89(10):1173-80.

8. Mathers WD, Choi D. Cluster analysis of patients with ocular surface disease, blepharitis, and dry eye. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004 Nov;122(11):1700-4.

9. InSite Vision. Comparative study of AzaSite plus compared to AzaSite alone and dexamethasone alone to treat subjects with blepharoconjunctivitis. 2008 Oct. Available at: www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00754949?term=azasite+dexamethasone&rank=1. (Accessed October 2010).

10. Alcon Research. A study to evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of TobraDex ST compared to AzaSite in the treatment of subjects with moderate to severe chronic blepharitis. 2010 Apr. Available at: www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01102244?term=azasite+chronic+blepharitis&ran=1. (Accessed October 2010).

11. Torkildsen GL, Cockrum P, Meier E, et al. Evaluation of clinical efficacy and safety of tobramycin/dexamethasone ophthalmic suspension 0.3%/0.05% compared to azithromycin ophthalmic solution 1% in the treatment of moderate to severe acute blepharitis/blepharoconjunctivitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010 Dec. [Epub ahead of print]

12. The epidemiology of dry eye disease: report of the Epidemiology Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007 Apr;5(2):93-107.

13. Donnenfeld ED, Mah, FS, McDonald MB, et al. New considerations in the treatment of anterior and posterior blepharitis. A Continuing Medical Education Supplement to Refractive Eyecare. 2008 Apr;12(4).

14. Driver PJ, Lemp MA. Meibomian gland dysfunction. Surv Ophthalmol. 1996 Mar-Apr;40(5):343-67.