|

The British Contact Lens Association (BCLA) recently published its long-awaited Contact Lens Evidence-based Academic Reports (CLEAR) in Contact Lens and Anterior Eye. Conceived by James Wolffsohn in June 2019, CLEAR brought together over 100 multidisciplinary experts in contact lenses to review and summarize the literature on contact lenses in a set of 10 articles covering topics including effect of contact lens materials and designs on the anatomy and physiology of the eye, contact lens optics, medical use of contact lenses, evidence-based contact lens practice, and contact lens technologies of the future.

I dove into the two reports dedicated to gas permeable (GP) lenses and materials to see what pearls we could take away.

The report on medical use of contact lenses was authored by Deborah S. Jacobs, MD, of the cornea and refractive surgery service at Massachusetts Eye and Ear and Harvard Medical School along with 11 optometric colleagues active in practice and research across the United Kingdom, Spain, Australia and the United States.1

The authors do an excellent job detailing the current lack of a field-wide, universally accepted definition of what constitutes “medical contact lenses.” Their consensus determined that medical contact lenses are those worn primarily to treat an underlying disease state or complicated refractive status; that is, for a reason other than cosmesis, or eliminating the need for spectacles.

|

|

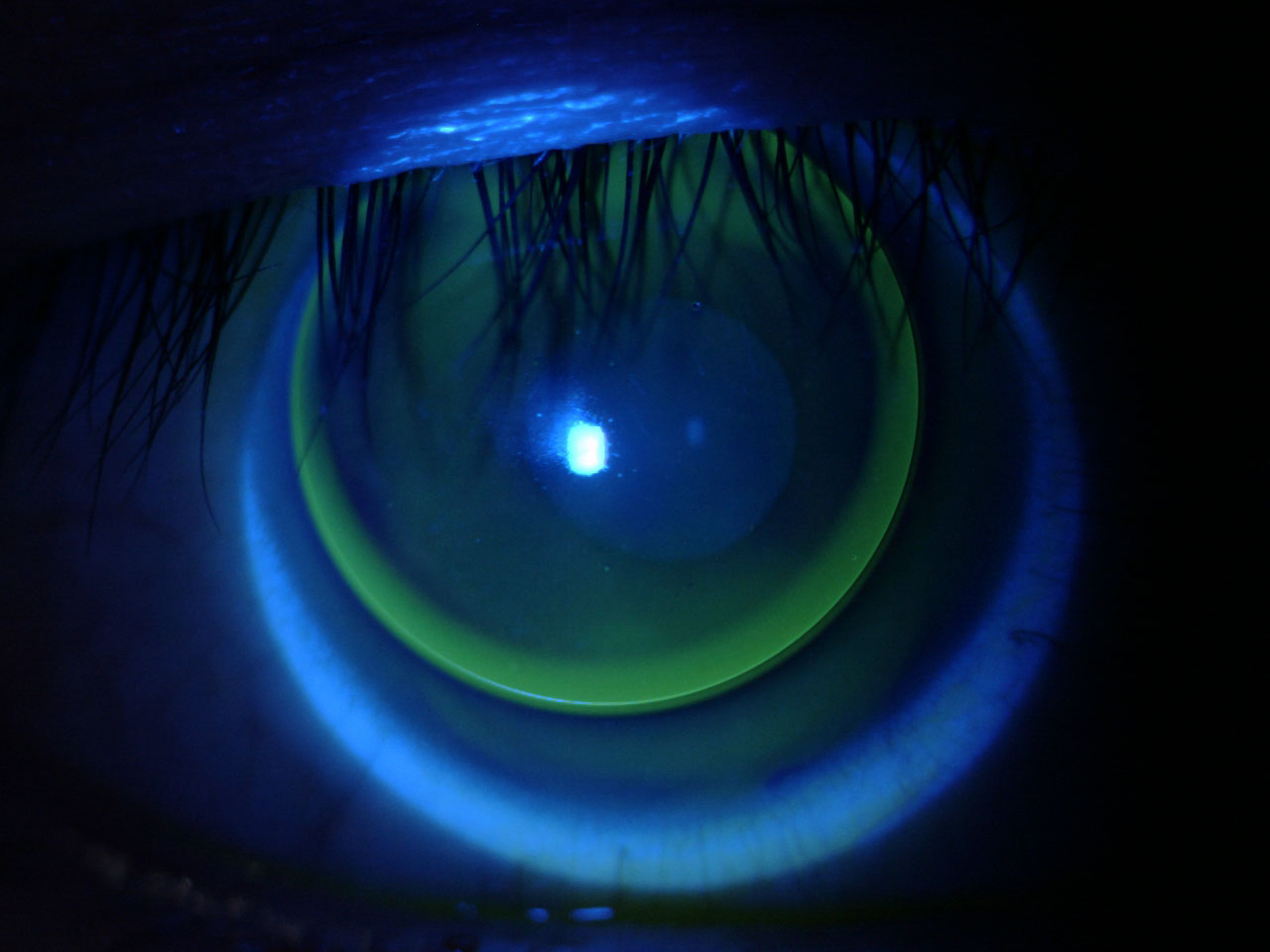

Fig 1. Lid-attached corneal GP lens fit on a patient with myopic astigmatism. Click image to enlarge. |

Therapeutic or Rehabilitative?

Beyond their consensus definition of medical contact lenses, this esteemed group additionally recommended two clinical definitions for medical use of lenses:

(1) As therapeutic (or bandage) contact lenses “for the treatment of ocular discomfort, to support the cornea after surgery, or when the cornea is being treated for an underlying disease state or to protect the cornea from the environment or mechanical interaction with the lids.”

(2) As a rehabilitative contact lens “prescribed for conditions that prevent a patient from achieving adequate visual function with spectacles because of high, irregular or asymmetric refractive error.” They add that “partially or completely occlusive lenses that improve function or cosmesis after trauma, surgery or stroke also fall into this category.”

Therapeutic lenses are used to treat, support or protect the cornea. Examples include a soft contact lens worn after refractive surgery or a scleral lens worn in exposure keratopathy. Rehabilitative lenses are used to treat high, irregular or asymmetric refractive error or worn as a partial or complete occluder.

Examples include custom-tinted black occluder lenses worn for amblyopia, large diameter custom soft lenses, custom soft toric hydrogel or silicone hydrogel contact lenses, or standard or custom lenses to correct anisometropia (asymmetry in refractive error between the two eyes).

When discussing contact lenses for medical purposes, the group identifies bandage lenses, stating that “while any CL might be used medically or as a therapeutic or bandage contact lens, some contact lenses are labeled for use as a bandage lens or with a therapeutic indication for use.” However, they note “the literature currently lacks well-controlled studies related to [soft] lens materials being used specifically for medical purposes.”

The report also outlines the medical purposes for which practitioners may fit contact lenses, including “treating patients with corneal ectasia, ocular surface disease, after ocular surgery and in the setting of high refractive error,” which is a definition borne out of the Scleral Lenses in Current Ophthalmic Practice study group’s 2018 publication on the prescribing patterns of scleral lens fitters.2

Rehabilitative Corneal GP Lenses

When specifically discussing corneal GP lenses, the authors outline suitability for two distinct conditions: aphakia and high refractive error. While the report also includes an assessment of the use of corneal GP lenses in the management of keratoconus, this falls more into the category of a therapeutic GP lens. In all cases, corneal GPs offer “superior visual correction provided by the rigid, regular front surface of the lens,” which can be most useful in high refractive error and corneal irregularity.

With the more widespread adoption of corneal GP lenses as the 20th century progressed, it became clear these lenses were useful in the correction of high ametropia. Contact lenses provide better acuity than spectacles for highly myopic refractive errors.3 In patients with high astigmatism, empirical fitting of either soft or corneal GP lenses can provide results that meet or exceed the vision achieved with spectacles. This is attributed to the increase in magnification of high minus corneal GP lenses when compared with spectacles.4 When considering anisometropia, good results can also be achieved in treating myopic anisometropic amblyopia with contact lenses.

|

|

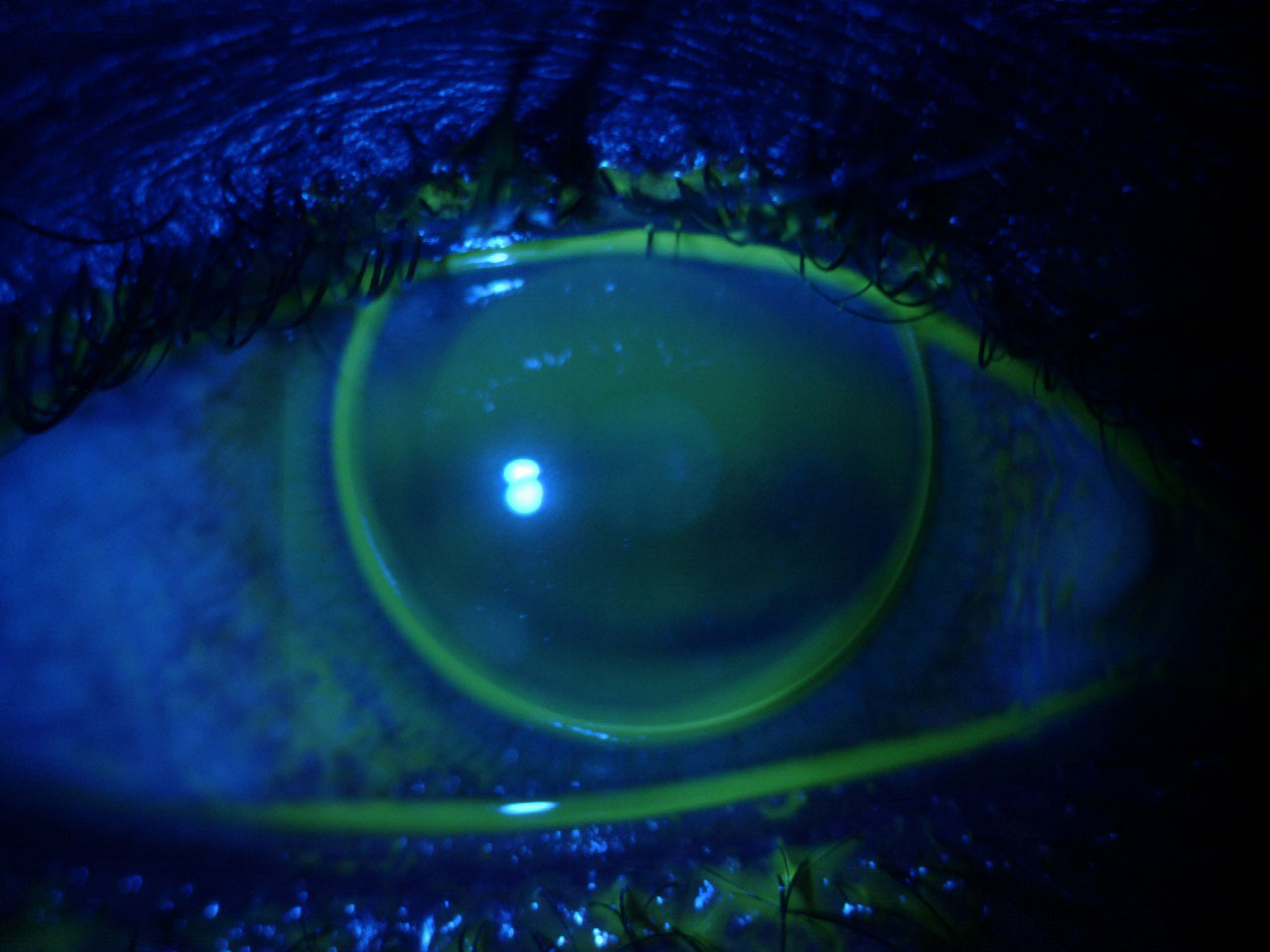

Fig 2. Corneal GP fit on a myopic patient with neovascularization due to previous overwear of a hydrogel soft lens. Click image to enlarge. |

Challenges and Complications

One of the challenges of GP lens fitting for rehabilitative purposes in aphakia is unilateral aphakia, where aniseikonia can be the limiting factor in successful wear of spectacles. The report outlines cases where contact lenses of varying types have been shown to provide some level of binocular vision. In addition, for patients with traumatic aphakia, there is often accompanying corneal irregularity and scarring, which can benefit from GP lens correction.

In cases of aphakia, much attention has been paid to the benefits of overnight contact lens wear to improve the patient experience. The reasoning is that our aphakic patients tend to be elderly and may face challenges with daily lens routines. The authors cite multiple studies that evaluated the risks/benefits of overnight wear in aphakia and found that while there are benefits in lens experience with GP and silicone elastomer lenses, there is also a high risk of adverse events including risk of microbial keratitis and vision loss.1

In cases of both aphakia and high refractive error, there can be corneal neovascularization that arises from poor oxygen transmission associated with lens thickness, lens material or overnight wear. In addition, simply achieving an optimal fit due to the lens thickness and fit dynamics can be a challenge. The report also reminds us of the challenges associated with fitting GP lenses in patients with ectopia lentis and Marfan syndrome, as these corneas tend to be flat with larger corneal diameters and higher levels of myopic and astigmatic refractive error.

Furthermore, corneal GP lens correction of highly myopic refractive error is associated with the development of ptosis, and the degree correlates to the degree of refractive error and duration of GP lens wear.5 This creates a potential issue in either unilateral lens wear or anisometropia, and given the utility of corneal GPs for treating these conditions, it is certainly something we should monitor if developing in our patients.

Whether you are fitting a “normal” refractive error or a more complex case with co-existing aphakia, anisometropia or amblyopia, corneal GP lenses can be an option for optimal vision correction and give the opportunity for long-term patient satisfaction, binocularity and even vision improvement when compared with spectacle lens wear. CLEAR gives us a well-referenced, well-thought-out, evidence-based summary of contact lenses that is going to be a resource in our industry for years to come.

1. Jacobs, Deborah S., et al. CLEAR–Medical use of contact lenses. Cont Lens and Anterior Eye, 2021; 44(2):289-329. 2. Nau, Cherie B., et al. Demographic characteristics and prescribing patterns of scleral lens fitters: the SCOPE study. Eye Contact Lens, 2018; 44(Suppl 1):S265-S272. 3. Astin, Christine LK. Contact lens fitting in high degree myopia. Cont Lens Anterior Eye, 1999; 22(Suppl 1):14-9. 4. Fonda, Gerald. Evaluation of contact lenses for central vision in high myopia. Br J of Ophthalmol, 1974; 58(2) (1974):141-7. 5. Watanabe, Akihide, Kojiro Imai, and Shigeru Kinoshita. Impact of high myopia and duration of hard contact lens wear on the progression of ptosis. Jpn J Ophthalmol, 2013; 57(2):206-10. |