Designing scleral lenses can seem daunting at first, and while there is certainly a learning curve, optometrists interested in this area of practice can find success with dedication and a well-informed approach.

Scleral lenses have become a valuable tool that can benefit a variety of patients such as those with irregular corneas, ocular surface disease and high levels of refractive error, including astigmatism and presbyopia. Since no two cases are the same, designing a scleral lens that meets the needs of your patients will take time and patience, though there are ways to streamline the process.

“Whether you are a novice or experienced, it is important to remember that you don’t know what you don’t know,” notes Christine Sindt, OD, professor of optometry at the University of Iowa. “We are constantly learning and evolving, and as we learn more about scleral lenses and the conditions we are treating, we will continue to refine our approach. It is important to cut yourself some slack and recognize where you are right now.”

Below, experts share their experiences with scleral lens design and discuss the various aspects of scleral lens fitting, including parameters of lens design as well as considerations for atypical corneas and patient communication. They offer 10 tips and tricks—in no particular order—to help you optimize your own technique.

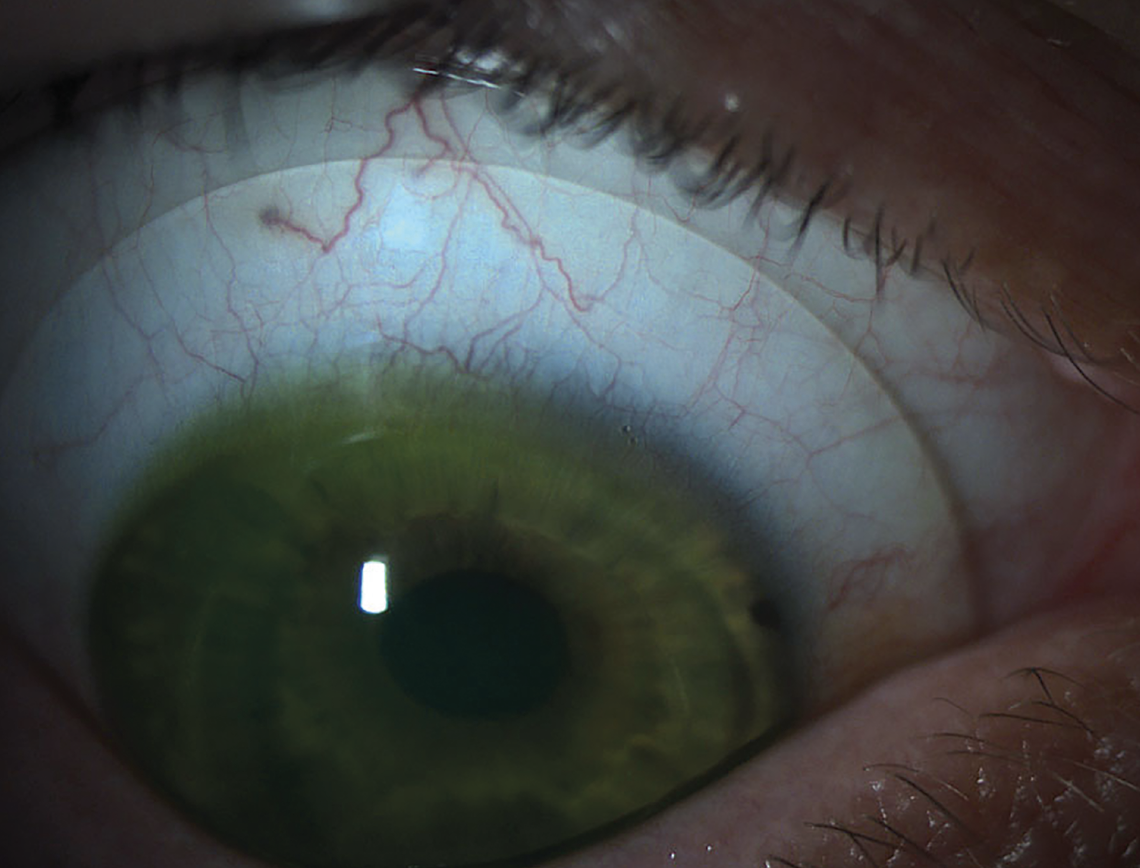

|

| Fig. 1. Scleral lenses are often the best choice to fit irregular corneas. Photo: Brooke Messer, OD. Click images to enlarge. |

Tip #1: Determine if your patient is a candidate.

Determine if your patient is a candidate. Before you even start designing a scleral lens, it is important to make sure that your patient is the right fit for this approach. Dr. Sindt advises taking a step back and asking yourself, “Is this the best option for the individual? Where is the patient mentally and emotionally in this journey?”

Additionally, consider whether the patient requires other care before you begin a lens fitting. Dr. Sindt notes that she often sees clinicians “initiating the scleral lens process before addressing the patient’s other physical needs because the patient is pushing for this.” In these cases, give yourself permission to say no to the patient and explain to them why a different approach is the better option right now, she suggests.

When determining if a patient is a good candidate, Shalu Pal, OD, who practices in Toronto, starts with a specialty lens assessment. “I make sure that the ocular surface is safe for a scleral lens to be worn and that scleral lenses are truly the best optical solution for the patient, in comparison to other, potentially less expensive options,” she says. “Before starting, I advise the patient of any conditions that need to be treated before we begin, such as blepharitis, meibomian gland dysfunction or allergies.

“To ensure the patient is ready for a fit, I review the fitting process, the time it takes to fit these lenses and the cost,” she adds. “I need the patient’s full agreement and understanding before we begin.”

Tip #2: Start with diameter.

Selecting the lens’s overall diameter is the first consideration in any scleral lens fitting, according to Melissa Barnett, OD, principal optometrist at the University of California Davis Eye Center, who notes that this is important for determining sagittal height.

One of the primary considerations when choosing the diameter is a patient’s topographic patterns and ocular anatomic factors, including height and length of the eyelids and eyelid spacing. Other aspects that can impact diameter are horizontal visible iris diameter (HVID), vertical visible iris diameter (VVID), limbus width and corneal sagittal height.1,2

“The practitioner should keep in mind that corneal sagittal height determines the width of the landing zone. The scleral peripheral zone width (landing zone and last peripheral zone width) is the last parameter that may affect the total diameter,” Dr. Barnett and specialty contact lens innovator, Daddi Fadel, DOptom, wrote in their Clinical Guide for Scleral Lens Success.1

When discussing scleral lens design tips, Dr. Barnett says, “Don’t be afraid to go larger in diameter. Often, you will see practitioners using a 14.5mm or 15mm lens; however, many patients will do quite well with a 16mm to 17mm lens.” This can be especially valuable for patients with dry eye, she notes. “In these patients, a larger lens is often better than smaller lens because anything under the lens will be bathed with fluid. So, even in a patient with a normal cornea, I would select a larger diameter lens to help them achieve greater relief from dry eye.”

A diameter of 16mm to 16.5mm is going to fit most eyes, emphasizes Greg DeNaeyer, OD, who practices optometry in Columbus, OH. However, he notes, there are always exceptions to the rule, one being the patient who has an exceptionally large corneal diameter (i.e., 12.2mm to 12.5mm). “Those patients are going to require a bigger diameter scleral contact lens for the fluid reservoir to be able to adequately vault from limbus to limbus,” he explains.

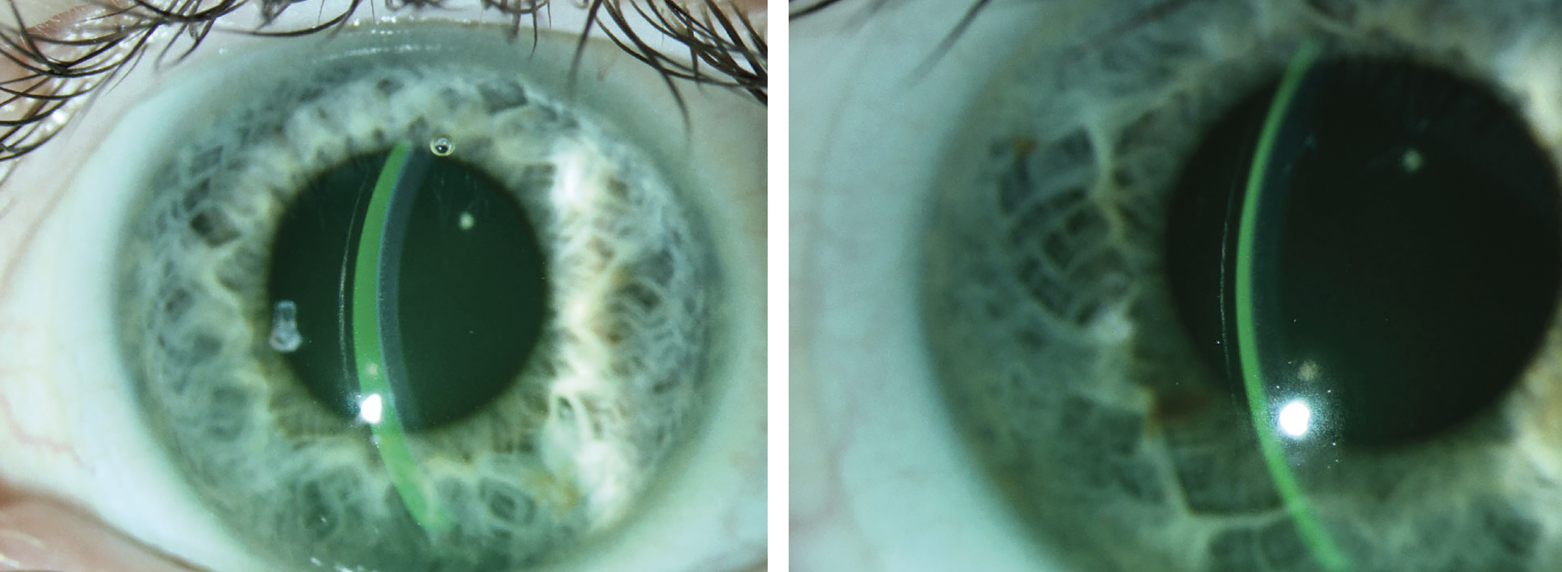

|

Fig. 2. (Left) A lens with proper clearance. (Right) A different lens showing excessive clearance, which could lead to decreased vision, post-lens debris and conjunctival impingement. Photo: Jeffrey Sterling, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

The other exception, beyond just a large corneal diameter, is keratoglobus, according to DeNaeyer, who notes that to vault the eye and have enough sagittal depth of the contact lens, you typically need a larger diameter lens.

For John Gelles, OD, who specializes in keratoconus and contact lenses at The Cornea and Laser Eye Institute of Teaneck, NJ, , his rule of thumb is to fit lenses proportionate to the disease. “If a patient has extensive dry eye that is all over the conjunctiva and covering the entire cornea, I’m going to fit the biggest diameter that I can fit onto that eye,” he explains.

“Now, for someone whose dry eye or other corneal pathology is limited to the cornea, I will opt for a smaller lens,” he adds. “A diameter of 21mm or 22mm is unnecessary in an eye where you are only dealing with corneal pathology.”

In addition to the size of the cornea (HVID) and choosing a large lens for dry eyes to cover more of the ocular surface and exposed conjunctiva, corneal shape also plays a role in determining the proper lens size, according to Dr. Pal. “A very steep cornea with a large sagittal height will require a larger lens so that it can gradually lift off the scleral and reach the apex of the cornea,” she explains. “If a smaller lens is chosen, the lens will ‘smash’ into the limbus and mid-peripheral cornea,” she says, causing discomfort and corneal damage.

“If the shape of the scleral is more spongy and irregular, opt for a lens that is further away from the limbus,” continues Dr. Pal. “When putting on a large-diameter lens, it will ‘sink’ more over time. A larger lens is also heavier and may decenter more due to the asymmetrical shape and the weight of the lens. The natural decentration of a lens is inferior and temporal.”

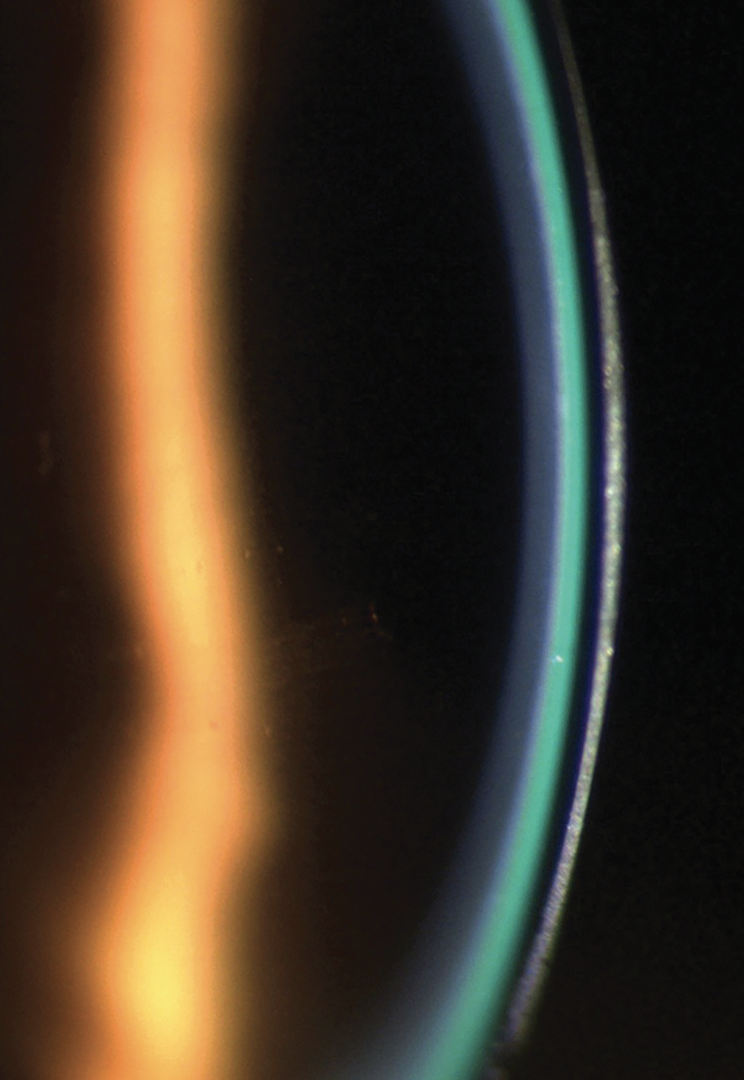

|

Fig. 3. A scleral lens demonstrating a 1:1 ratio of lens thickness (dark band) to tear layer (green band). Photo: Irene Frantzis, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Tip #3: Corneal clearance depends on the condition.

Typically, less central corneal clearance is needed for normal eyes, while more clearance is preferred in cases of ocular surface disease and irregular corneas. Optometrists can adjust corneal clearance by changing the base curve or by independently increasing or decreasing the lens sagittal height, Dr. Barnett explains (Figure 2).

In Dr. Gelles’s practice, he considers most fits successful with 100µm to 400µm of clearance over the apex. However, he notes that less clearance can also be acceptable in some cases. “If I see a patient at the end of the day and the lens is fully settled after two weeks of wear, I would consider 50µm of clearance fair, but generally my goal is to keep them within that 100µm to 400µm range. This is variable based on condition.”

The tear reservoir or clearance of a lens will be very uniform across the cornea of a normal patient or a dry eye patient who has no underlying corneal irregularity, explains Dr. Pal, while also noting that the clearance of an irregular cornea, such as a keratoconic patient, will vary depending on the location and severity of the cone shape (Figure 4).

|

| Fig. 4. A fluorescein pattern of a scleral lens on an eye with keratoconus. Note complete clearance of the cornea. Photo: Melissa Barnett, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

“You need to ensure that you look at the entire cornea to determine corneal clearance. The advancements in lenses today allow us to adjust corneal clearance with the use of quad-specific limbal curves, mid-peripheral curves and, in some cases, central curves. The key is to make sure you look at the whole cornea from edge to edge and top to bottom to look for areas of excessive clearance or inadequate clearance.”

Since lenses will continue to settle over several months of wear, it is important to keep watching this drop in clearance, Dr. Pal recommends, while adding that patients should “return for follow-ups before their warranties are complete and six months after a fit is complete to ensure we do not have touch of the lens over time.”

Tip #4: Understand the disease and lens geometry.

Before you can design a lens, you must have a clear picture, not only of the condition you are addressing, but also the lens geometry, according to Dr. Gelles. This is especially important in cases of atypical anatomy. “ODs need a topographer at the very least—and ideally, a tomographer—to not only understand the geometry, but also follow the disease state. Most patients are using these lenses for progressive corneal diseases like keratoconus or post-refractive ectasia.”

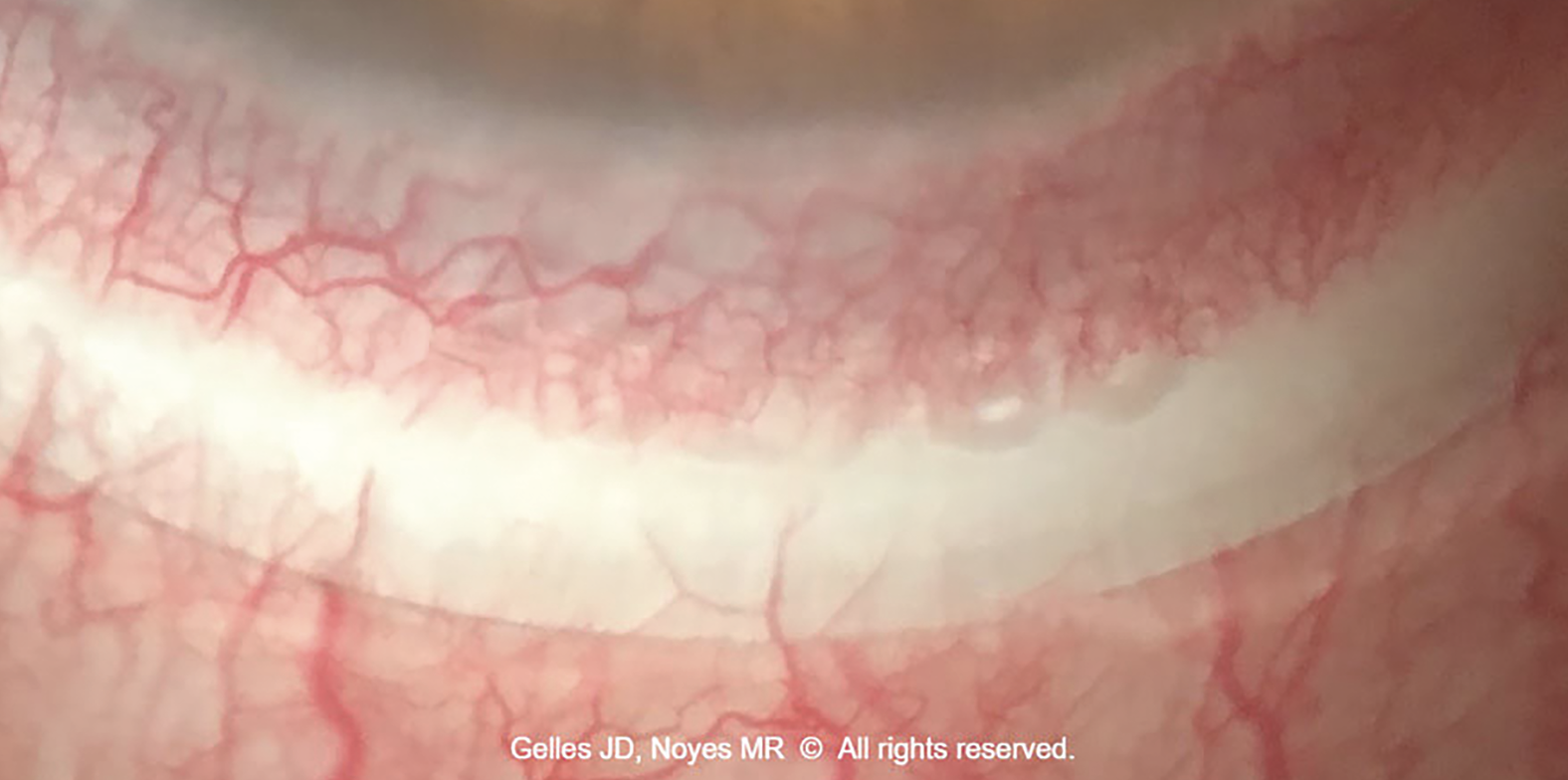

It is important to have a clear understanding of the lens geometry and the ocular contour for optimal lens design. “You need to know the corneal diameter, the difference between an oblate and hyperprolate cornea, the contour of the sclera and be aware of any abnormality on the conjunctiva,” he notes. “This is going to determine which scleral lens you use. For instance, some of the available lenses have fixed zones, no ability to add advanced haptic features or do not allow you to control the profile of the inner geometry of the lens, so I may end up with almost no clearance or touch or compression over the areas that I wanted clearance and large amounts of clearance over the area that I don’t (Figure 5).” This is why, according to Dr. Gelles, having knowledge of the design is very important.

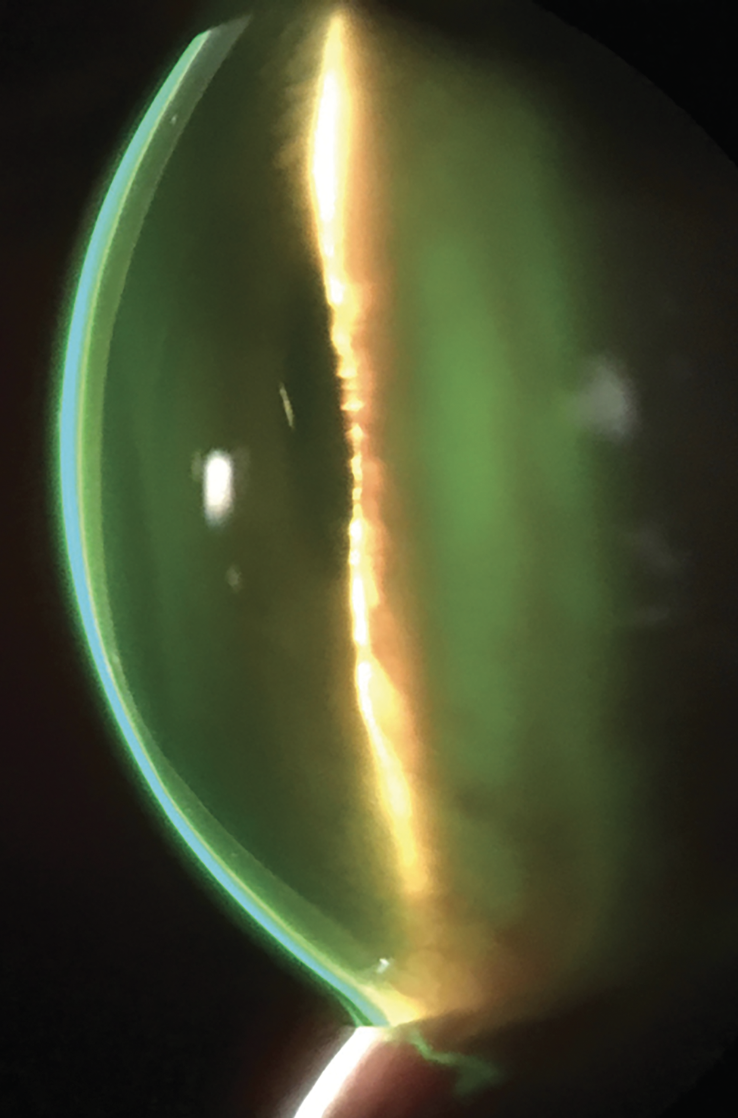

|

| Fig. 5. This scleral lens landing zone displays severe (fine and large vessel impingement) conjunctival compression. The left edge of the lens is too flat (note the 0.5mm band of compression located 0.5mm from the lens edge), and the right edge is too steep (note the compression starts at the edge and extends 1mm inward). To improve this landing zone fitting relationship, steepen the left side and flatten the right side by using a toric periphery. Photo: Marcus R. Noyes, OD, and John D. Gelles, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Tip #5: Take advantage of available tools.

There are a number of options available for getting the information you need to properly design and fit a scleral lens. One that can be particularly helpful is scleral topography and profilometry.

This can help streamline the scleral lens fitting process and empirically provide either the best-fit lens or free-form lens that match the ocular surface on a micron scale, according to Marcus Noyes, OD, who practices in Columbus, OH. He noted in a previous Review of Optometry article, “This can help you save time and money while ensuring optimum comfort and vision for your patients. These tools can also be combined with existing technologies such as HOA correction and decentered optics to create truly personalized options per patient, per eye.”3

Dr. DeNaeyer, who has been fitting scleral lenses based on corneoscleral topography since 2015, has found that there are multiple ways to approach the use of this technology. For one, he explains, ODs can gather data on corneal and scleral shape, and those measurements can then help them to more efficiently use their diagnostic lens sets of choice.

“For instance, if the data shows that the sclera is toric, you will want to use a scleral lens with the toric landing zone, even diagnostically,” he says. “Additionally, you are also given the direction and amount of toricity. This is a much faster way to get the fitting process started, because without this data, the very first lens you put on the eye is really just a blind diagnostic trial.” Because of this, Dr. DeNaeyer says, “I always encourage practitioners to try to get that type of measurement.”

After using corneoscleral topography, Dr. DeNaeyer then uses software to design the scleral lens. “You can either customize a standard design that is available from one of the various manufacturers or you can use that three-dimensional model dataset to design a ‘free-form’ scleral contact lens that is completely customized to a patient’s eye surface.”

That being said, practitioners shouldn’t be discouraged if they don’t have the latest technology at their disposal right now. Use the fitting guide and connect with your laboratory consultants for additional support, suggests Dr. Barnett.

“My recommendation for practitioners new to scleral lens fitting is to become an expert in one or two diagnostic fittings and then branch out from there,” she says. “If you aren’t sure where to begin, look at your patient population and their needs. In your practice, do you see a lot of irregular corneas, post-surgical, dry eye, etc.? This will help shape your scleral lens practice.”

When investing in more advanced equipment such as profilometry or impression-based designs, Dr. Sindt recommends that ODs who are just starting out consider their options. While it may seem overwhelming or costly, there can be value in investing in the right equipment sooner rather than later.

“While it may feel less expensive to start solely with trial-and-error fitting, you will spend more time and make more errors, which comes at a cost as well,” says Dr. Sindt. “Chair time is very expensive, and I think we often underrate what our actual chair time is worth.”

Tip #6: Use consultants as a resource.

The design and fit of every scleral lens are unique, which is why optometrists should take advantage of every resource, including laboratory consultants. “Lab consultants are your partners to help you with your fits and most importantly give you the confidence in their products to help you make changes on your own,” says Dr. Pal. “They enjoy working with ODs and should always be treated with respect. We couldn’t do our job without them.”

Successfully working with consultants depends on effective communication, emphasizes Dr. Gelles. “Verbal or written descriptions are open to interpretation,” he notes. “The best way to ensure consistency and clear understanding is to share photos and videos with your consultants when troubleshooting a lens design.”

“Your style of communication is important to match with your consultant and learning to speak the same language is vital,” adds Dr. Pal. “I always design my lenses late at night via email. If a consultant wants to only discuss fits on the phone, we won’t work well together because our ‘working times’ won’t overlap.”

While consultants are an invaluable resource for the optometrist, Dr. Gelles urges ODs not to expect the laboratory to do your work for you. “They are a helping hand that will guide you to success, but it is up to you to take the lead and design the lens that will best fit your patient.”

|

| Fig. 6. To accommodate a scleral or conjunctival elevation due to abnormalities such as pinguecula, clinicians have several options, such as adjusting the diameter, adding a focal area of vault or notching the lens edge. Photo: Marc Bloomenstein, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Tip #7: Contend with pinguecula and other obstacles.

Another challenge optometrists may face during the scleral lens fitting process is scleral and conjunctival elevation. Some examples include pinguecula (Figure 6), pterygia, tube shunts and scarring due to prior injury or surgery. Without the optimal fit, lenses can cause discomfort, redness and other issues for these patients.

There are a number of ways to address these obstacles, such as making the diameter smaller or larger, adding a focal area of vault or notching the lens edge. Impression-fit lenses may also be an effective approach depending on the individual case.4

Assessing the vault of a pinguecula or a conjunctival obstacle can be tricky at first, acknowledges Dr. Pal. “I used my slit lamp reticle to determine the number of degrees that the elevation spans and I use conjunctival photos, OCT images, good estimations and, most importantly, my consultants to help determine how large to design a vault or channel.”

Pinguecula are very common, and optometrists must be prepared to take that into consideration, notes Dr. DeNaeyer. “Depending on the patient, it may be mild enough not to cause an issue; however, any pinguecula that is 200µm in elevation or more is potentially problematic, so ODs will have to troubleshoot.” He recommends adjusting the diameter if the cornea allows, or you could do a localized vault. “This is another example where corneoscleral topography can be valuable. However, if you don’t have this data, as mentioned above, 200µm is a good number to keep in mind and a good place to start if you think you need a localized vault or other adjustments to improve the fit for this type of patient,” says Dr. DeNaeyer.

Tip #8: Don’t make adjustments too soon.

Practitioners, especially those just beginning to fit sclerals, may have a tendency to make changes to the lens fit too early in the fitting process, suggests Dr. DeNaeyer. “This can lead to unnecessary changes that might actually make the fit worse rather than better.”

When dispensing lenses, Dr. DeNaeyer’s philosophy is that the patient needs to have acceptable vision that meets standards for driving, and the lens has to fit in a healthy way. “If I meet those two objectives, I am not changing the lens that day. I will train the patient, if they haven’t already been trained on scleral lenses, and send them home.”

This allows patients the opportunity to start wearing the lenses in their “real life,” and when they come back to the office, “we know that it has fully settled,” he adds. “At that point, adjustments can be made depending on the practitioner’s objective assessment as well as what the patient tells us subjectively.”

Tip #9: Know when advanced lens designs are needed.

When faced with advanced anatomical challenges or more complicated cases, optometrists will likely have to look beyond what a traditional scleral lens can offer.

“Take, for instance, my two patients this week who had bilateral filtering procedures for glaucoma (Ahmed valves) in both eyes,” says Dr. Gelles. “The tissue that overlays the tube in those eyes can be fragile, and if you don’t have the technology that can contour to that area, you’re going to be in a position where you’re going to put unwanted and dangerous amounts of pressure and rubbing over that area. This will lead to the breakdown of that tissue and significant complications.”

In cases like this, it is important to have advanced tools such as scan or impression-based design to create free-form geometries, suggests Dr. Gelles. “Even if you don’t adopt these more advanced technologies, you should know the technology exists. You can either adopt this approach yourself or refer to a colleague who does have the technology to take care of these patients.”

Tip #10: Ask for patient feedback.

Dr. Barnett always asks her patients about their vision and how the lens feels to get a complete picture. “The patient perspective is critical,” she says. “I ask my patients if the lens is comfortable and how they perceive their vision.

“For example, a patient with keratoconus whose vision is 20/20 may report blurry vision. In that case, we probably need to correct the HOAs,” says Dr. Barnett. “This is why getting subjective feedback in addition to objective evaluations is so important.”

Both positive and negative feedback is needed to help the fitting process. If a patient is happy with the comfort and vision of the lens and it is not causing any harm, we can stop, notes Dr. Pal.

“If troubleshooting vision or discomfort, it is important to have a clear understanding of where the discomfort is coming from and if the discomfort is felt when the eyes are open or closed,” she says. “This will help you pinpoint where the problem is where to make changes to improve the lens fit.”

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to scleral lens design and every practitioner has their own unique philosophy. With the right tools and knowledge, ODs who have a passion for—and recognize the nuances of—scleral lens design can help their patients thrive.

No matter where you are on your scleral lens journey, there is always room for growth. With more experience comes more confidence. Given the ongoing advancements in the field, it is also important to stay informed on the latest technologies and research.

“I never fit the same lens twice. By the time a patient returns for a new lens, either I have learned something new, enhanced my skills or new technology is available to improve on the previous lens design,” says Dr. Pal.

“We are in a very exciting time of fitting lenses with so much advancement in technology,” she concludes. “I am always pushing to improve a patient’s comfort and vision. Refitting patients is beneficial to both the patient and myself. They get a better fitting lens and I improve my skills and experience. With the use of scleral lenses, we have an incredible ability to change the lives of our patients.”

1. Barnett M, Fadel D. Clinical guide for scleral lens success. www.scleralsuccess.com. 2. Barnett M, Johns LK (editors). Ophthalmology current and future developments; contemporary scleral lenses: theory and application. Bentham Books. 2017;4. 3. Noyes M. Scleral topography: measuring and matching its shape. Review of Optometry. Published September 15, 2021. www.reviewofcontactlenses.com/article/scleral-topography-measuring-and-matching-its-shape. Accessed August 26, 2023. 4. Bedi M. Take a Scleral Lens Virtual Workshop. Review of Optometry. Published October 15, 2022. www.reviewofcontactlenses.com/article/take-a-scleral-lens-virtual-workshop. Accessed August 26, 2023. |