The clinical entity known as contact lens-induced acute red eye, or CLARE, is an inflammatory reaction of the cornea and conjunctiva associated with overnight contact lens wear. It is also commonly referred to as acute red eye or tight lens syndrome. Often, the patient will present to your practice wearing dark sunglasses or clutching a box of tissues in an effort to cope with their symptoms. While treatment is relatively straightforward, episodes of this condition can recur; thus, our job as clinicians is not only to treat the condition in its acute stage, but also to educate the patient and give them the tools to return to lens wear in the healthiest possible manner.

Signs and Symptoms

CLARE is typically characterized by sudden onset of unilateral eye pain, photophobia, epiphora and ocular irritation. Accompanying slit lamp signs include diffuse conjunctival and limbal hyperemia, as well as the presence of multiple corneal epithelial and subepithelial infiltrates. The infiltrative reaction is generally located in the corneal periphery and mid-periphery; when sodium fluorescein stain is instilled in the eye, the infiltrative areas do not typically exhibit overlying punctate staining, indicating minimal epithelial involvement.3,4 In more severe cases of CLARE, corneal edema or anterior uveitis may also be present, although these signs are not common.1,2 Visual acuity is usually unaffected.

It is prudent to ask patients presenting with CLARE symptoms about any recent illnesses, including symptoms of the common cold such as headache, fatigue and runny nose. Often, upper respiratory tract infections are associated with gram-negative organisms like Haemophilus influenza.1,2 One study found that patients who were colonized with H. influenzae were more than 100 times as likely to have had a CLARE or infiltrative response than those subjects who were not colonized with this bacterium.5

| |

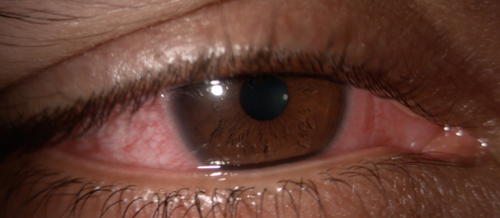

| Acute contact lens-associated red eye presentation in a 28-year-old Indian male. He noted associated blurry vision, foreign body sensation and photophobia. After a 10-day course of tobramycin/dexamethasone suspension QID and preservative-free artificial tears every hour for relief, he reported a significant improvement in symptoms. (Case and photo courtesy of Kelli Theisen, OD.) |

Case History and Evaluation

Typically, the most reliable way to accurately diagnose CLARE is with a complete case history and assessment of the symptoms mentioned above. By definition, CLARE is associated with sleeping while wearing contact lenses.2,3 This can be anything from a short afternoon nap to a full night of extended wear—the fact that the eye is closed for an extended period of time is key to our diagnosis. So, consider asking all your contact lens patients how many times per week they sleep or nap in their lenses as part of your routine history sequence.

Knowledge of the patient’s habitual lens type and wearing schedule may also have some value in our diagnostic considerations. Conventionally, CLARE is associated with tight fit or poor movement of extended-wear, low oxygen permeability, high water content hydrogel lenses. However, note that CLARE can also be caused by extended wear of silicone hydrogel lenses, which have significantly risen in market share in the United States in the last decade.1,6 CLARE has been reported to occur in 34% of continuous wear hydrogel lens patients and less than 1% of silicone hydrogel extended wear patients.7-9 Reports have also linked CLARE to extended wear gas permeable (GP) lenses, high oxygen permeability silicone elastomer lenses and overwear of daily disposable soft contact lenses.10

In the absence of a lens fit evaluation, history questions regarding hours per day of lens wear and difficulty with lens removal at the end of the day may assist in diagnosis. If you are able to assess the lens on-eye, pay special attention to lens movement and push-up test results. Note, however, that there are reported cases of CLARE occurring with well-fit contact lenses showing adequate movement.10,11

Etiology

While the etiology of CLARE is not completely understood, it is generally classified as an inflammatory event of the cornea and conjunctiva. General risk factors include wear of high water content lenses, wear of tight fitting lenses and history of a recent upper respiratory tract infection.2

One commonly cited cause of CLARE is colonization of the lens surface with gram-negative bacteria, specifically H. influenzae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Serratia marcescens.12 An inflammatory response is triggered by endotoxins released by the breakdown of bacterial cell walls. The condition is worsened in the tight lens environment because of lens dehydration, minimal lens movement, decreased tear exchange and hypoxia.1,7,10,12,13

In the inflammatory process, limbal vasodilation occurs, followed by release of white blood cells, and then infiltration of the injured tissue by polymorphonuclear leukocytes and other cells. This collection of inflammatory cells within the cornea forms what we call an infiltrate. The result is CLARE and its associated signs of conjunctival hyperemia and corneal epithelial and subepithelial infiltrates.7

Differential Diagnosis

In a case that may be CLARE or another corneal infiltrative event (CIE), the most important element to consider is whether the presenting condition is infectious or non-infectious.

Due to its sight-threatening potential if left untreated, microbial keratitis (MK) should be high on the list of differentials in any contact lens wearer presenting with a red eye. To differentiate MK from other CIEs, look for a discrete area of fluorescein staining, typically greater than 1mm diameter and often located in the central cornea. There may also be lid edema, a reactive ptosis, and more moderate to severe pain symptoms that worsen with lens removal. Anterior chamber cells and flare and mucopurulent discharge are more common in MK than CLARE and CLPU.3 A positive bacterial culture or the presence of tear film exudate can also help make an MK diagnosis.

CLARE can also appear similar to conditions like contact lens-induced peripheral ulcer (CLPU) and infiltrative keratitis (IK).3 However, while CLARE typically presents with multiple small focal and diffuse infiltrates that do not stain with fluorescein, CLPUs are characterized as single circular focal infiltrates up to 2mm in diameter that pick up fluorescein stain. IK is associated with Staphylococcal hypersensitivity and may occur in one or both eyes showing multiple small infiltrates with or without corneal staining. A careful history and slit lamp examination can help guide your diagnosis.

The remaining CIEs are categorized as asymptomatic and clinically insignificant.3 Asymptomatic infiltrative keratitis (AIK) and asymptomatic infiltrates (AI) are simply differentiated from CLARE in that they are seen on physical exam but carry no entering complaints. Other differentials to consider include: chlamydial conjunctivitis, trachoma, adenoviral infection, epidemic keratoconjunctivitis, Staphylococcal marginal keratitis, Thygeson's superficial punctate keratitis and herpes simplex keratitis.14

Treatment and Management

Management of CLARE always begins with discontinuation of contact lens wear. Beyond that, the condition is often self-limiting and may not require therapeutic intervention—in many cases, palliative treatment with artificial tears will suffice. However, we often prescribe additional therapeutic options to promote healing and improve patient comfort. Depending on severity, the infiltrates can take days to weeks following cessation of lens wear to heal.

Since many of the signs and symptoms of CLARE mimic those of microbial keratitis, it is prudent to instill sodium fluorescein and assess the corneal integrity for any epithelial disruption. Typically, there is minimal to no epithelial disruption with CLARE; however, if there is corneal staining present in association with an infiltrate, the diagnosis no longer clear-cut and the lesion becomes suspicious for MK. In such cases, conservative management warrants using a topical antibiotic for at least the first 48 hours of treatment. Some practitioners may prefer to address both the inflammation and risk of infection as quickly as possible by prescribing a combination topical antibiotic/steroid from the start. Recommended follow-up is daily until signs of improvement are shown.

In cases where the photophobia is particularly symptomatic, or where there is an accompanying anterior uveitis component, application of a topical cycloplegic agent is warranted for at least the first 24 hours. Topical and oral NSAIDs are also effective adjunct treatment options to quell the discomfort. If cells and flare persist, consider addition of a topical steroid to the regimen.

After complete healing, patients can resume lens wear using a fresh lens right out of the vial or blister pack. Consider changing lens fit, material, modality and/or replacement schedule prior to resuming lens wear to reduce potential for reoccurrence. For example, if the habitual lens was a tight fit, try selecting different base curve or diameter to improve movement and centration. If the patient has a history of lens abuse or overwear, switch them to a daily disposable lens design instead. Also, consider refitting patients into GP lenses—patients with a history of soft lens complications often adapt well to GP lenses and appreciate the benefits they provide.

It is important to note that recurrence of inflammatory complications can happen in 50% to 70% of wearers who resume hydrogel extended wear after resolution of their initial episode of CLARE.15 Additionally, patients who have had a CLARE episode retain higher levels of limbal injection, bulbar injection and conjunctival staining afterwards compared with controls.9 Careful slit lamp examinations and shorter intervals between contact lens appointments following a CLARE episode may be the best practice to follow based on your clinical judgment.

Above all, patient education plays an important role in preventing corneal infiltrative events such as CLARE. Stressing the importance of appropriate lens replacement, wear and care schedules to all of your contact lens patients can promote better patient adherence to our recommendations.

Patients should be advised to stop wearing their lenses while ill and when lens wear is uncomfortable or painful, particularly while their eyes are closed. For patients who have had a CLARE episode, emphasizing the risk of recurrence as well as a review of symptoms to look out for may also be helpful. Be sure to also provide an easy way for patients to contact your office in case of an emergent issue so that they end up in the best hands possible should another complication occur.

Dr. Sicks is an assistant professor at Illinois College of Optometry in Chicago. She is involved in the contact lens didactic curriculum and also serves as a clinical attending physician in the Illinois Eye Institute’s Cornea Center for Clinical Excellence.

1. Dumbleton K, Jones L. Extended and Continuous Wear. in Clinical Manual of Contact Lenses. E. Bennett and V. Henry, Eds. Williams and Wilkins. 2008:410-443.

2. Stapleton F, Keay L, Jalbert I and Cole N. The epidemiology of contact lens related infiltrates. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84(4):257-272.

3. Sweeney DF, Jalbert I, Covey M, et al. Clinical characterization of corneal infiltrative events observed with soft contact lens wear. Cornea. 2003;22(5):435-442.

4. Sankaridurg PM, Holden BA, Jalbert I. Adverse events and infections: which ones and how many? In e. Sweeney D, Silicone Hydrogels: Continuous Wear Contact Lenses (pp. 217-274). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

5. Sankaridurg PR, Willcox MD, et al. Haemophilus influenzae adherent to contact lenses associated with production of acute ocular inflammation. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34(10):2426-2431.

6. Nichols JJ. Annual Report: Contact Lenses 2013. Contact Lens Spectrum;29(January 2014):22-28.

7. Zantos SG, Holden BA. Ocular Changes Associated with Continuous Wear of Contact Lenses. The Australian Journal of Optometry. 1978;61(12):418-26.

8. Nilsson, S. Seven-day extended wear and 30-day continuous wear of high oxygen transmissibility soft silicone hydrogel contact lenses: a randomized 1-year study of 504 patients. CLAO J. 2001;27(3):125-36.

9. Stapleton F, Keay L, Jalbert I, Cole N. Altered Conjunctival Response After Contact Lens–Related Corneal Inflammation. Cornea. 2003;22(5):443-7.

10. Sankaridurg PM, Vuppala N, Sreedharan A, et al. Gram negative bacteria and contact lens induced acute red eye. Indian J Ophthalmol, 1996;44(1):29-32.

11. Crook, T. Corneal infiltrates with red eye related to duration of extended wear. J Am Optom Assoc. 1985;56(9):698-700.

12. Holden BA, La Hood D, Grant T, et al. Gram-negative bacteria can induce contact lens related acute red eye (CLARE) responses. CLAO J. 1996;22(1):47-52.

13. Binder PS. The physiologic effects of extended wear soft contact lenses. Ophthalmology. 1980;87(8):745-9.

14. Robboy MW, Comstock TL, Kalsow CM. Contact Lens-Associated Corneal Infiltrates. CLAO J 2003;29(3):146-54.

15. Sweeney DF, Grant T, Chong MS, et al. Recurrence of acute inflammatory conditions with hydrogel extended wear. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sc 34:S1008.