We all have patients who are contact lens dependent, whether it’s for drug delivery, modulation of ocular discomfort, improvement of visual acuity or all three. They may suffer from a variety of anterior segment disorders, including severe dry eye, keratoconus, irregular astigmatism, corneal dystrophy, stem cell failure, trichiasis or superior limbal keratoconjunctivitis, among others (figure 1). These patients may also have coexisting ocular surface disease (OSD) that threatens their ability to wear contact lenses. They are depending on us to “fix the problem.”

These conditions may be intermittent and seasonal or perennial and permanent, and it is essential that we provide these patients with effective solutions swiftly and successfully. Let’s take a closer look at how to troubleshoot cases where OSD patients are contact lens dependent and discontinuing lens wear is not a viable option.

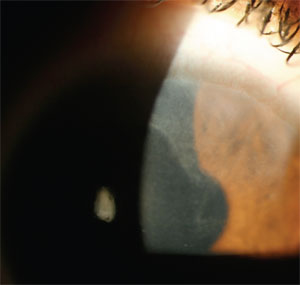

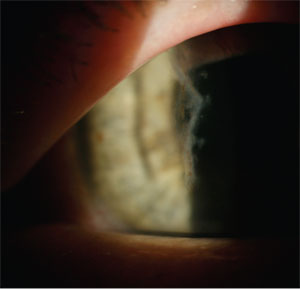

1. In this patient, stem cell

failure extends from the superior limbus into the patient’s line of

sight. Anterior stromal scarring and irregular astigmatism are

disruptive for best-corrected acuity and require a contact lens to

improve vision. While mild cases of stem cell failure might benefit

from soft lens wear, more advanced cases may require treatment before

fitting can be attempted.

Selecting Potential Candidates

In the world of surgery, the best way to avoid a problem is to not create one. This mantra also applies for clinicians faced with a patient who must wear contact lenses for vision while also manifesting a pathologic anterior segment condition. A careful preemptive analysis can make the difference in determining who is a better fitting risk for contact lenses.

The most critical tasks that the eye care practitioner must perform are a thorough anterior segment evaluation and a detailed discussion with the patient (or, possibly, a family member) about any findings in relation to the case history. A well-informed and motivated patient can benefit from this process immeasurably.

From the doctor’s perspective, it must be determined if the patient possesses sufficient ocular health to support wearing a contact lens and if wearing a lens provides a measureable amount of visual and/or physical improvement. From the patient’s standpoint, they just want to have appreciable benefit from wearing a contact lens. For instance, if the patient has 20/20 uncorrected vision in the “good” eye and 20/40 in the “damaged” eye, yet isn’t visually or physically symptomatic, then he or she might not be an ideal candidate for lens wear. However, if the reduced vision is bothersome, and the patient suffers from ocular discomfort, then there is value in moving forward. If this same patient has severe rheumatoid arthritis, and poor finger dexterity hampers his or her ability to perform insertion and removal, lens wear may require the assistance of a friend or family member. As we know, every case is unique and must be evaluated on its own merits.

Your slit lamp examination will identify factors that can make or break a fit and ultimately the patient’s wearing experience. The importance of uncovering these potential pitfalls early on is essential in all cases, but it takes on even greater importance in your contact lens-dependent population. For example, profound posterior blepharitis, dry eye concerns or allergic conjunctivitis need to be resolved prior to fitting to improve the odds of success. Artificial tears, topical allergy medications, Restasis (cyclosporine 0.05%, Allergan), hot compresses and punctal plugs are all part of your treatment armamentarium to improve the status of the ocular surface. Additionally, addressing adnexa issues, such as nocturnal lagophthalmos, eyelid laxity or malposition is essential and may require corrective measures such as nighttime lubricants or sleep masks, or potentially more aggressive oculoplastic intervention. These will be further discussed later in this article.

Education is Key

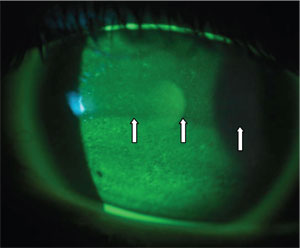

2. This patient exhibits inferior

punctate dessication and evidence of lagopthalmus. Note the demarcation

line in the flourescein pattern evidenced by the white lines with the

patient’s partial blink pattern.

Many patients have biased expectations predicated on what their friends and family have experienced, but they need to understand that their particular situations are not merely cosmetic but medically necessary. They will need to be prepared for the possibilities of an extended time commitment and increased expense, as well as an adaptation period due to initial discomfort or lens awareness. There is much to be gained by a trial lens fitting for those patients who are feeling tentative; this extra step will help them decide if they are willing and able to proceed. Like refractive surgery candidates, “underpromising and overdelivering” an outcome with the complex contact lens patient will generally lead to a happy patient. Documentation of all exams and discussions with the patient is invaluable as you move ahead.

Treat the Underlying Issues

For the purposes of this article, let us look at individual pieces of the anterior segment puzzle that would affect lens fittings and briefly discuss some concerns. It is the treatment of basic ocular surface findings that can increase one’s success when fitting.

• Allergic conjunctivitis. Many anterior segment diseases have an underpinning of ocular allergy. You can offer a prescription topical anti-allergy medication, such as Elestat (epinastine, Allergan), Patanol, Pataday (olopatadine, Alcon), Bepreve (bepotastine, ISTA) or Alrex (loteprednol, Bausch + Lomb), or a non-prescriptive alternative such as Zaditor (ketotifen, Novartis) or Alaway (ketotifen, Bausch + Lomb), based on your clinical judgment about what is best for the patient. Controlling this condition is especially important in keratoconus, where eye rubbing is a contributing factor to the disease.1 Another cause for papillary changes is floppy eyelid syndrome, which is often associated with obstructive sleep apnea.2 During sleep, there can be spontaneous eversion of the upper lids which, as it rubs against the pillow or sheet, causing a velvety papillary reaction and mucous production. A hard, clear eye shield at night and a sleep study are mandatory for these cases. Unresolved obstructive sleep apnea can be fatal.3

• Dry eyes. It is well understood and accepted that dryness is the number one cause of contact lens dropout, but failure is not an option for patients with no practical visual alternatives. We must ensure that the tear film is stable and viable, and our options are many. We can achieve improvement in tear film viability through utilization of artificial tears, nighttime ointments, low-dose topical steroids, Lacrisert (hydroxypropyl cellulose ophthalmic insert, Aton), Restasis, punctal plugs, permanent punctal cauterization, hot compresses, lid wipes, nutritional supplements, sleep masks or goggles and daytime barrier protection, such as 7Eye (formerly Panoptx) or Wiley X eye wear. Some patients with systemic related dry eye, such as Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, hyperthyroidism, Graves’ ophthalmopathy, graft vs. host disease (GVHD), or stem cell failure might require extended wear soft contact lenses or large-diameter rigid gas-permeable lenses. For soft lenses, we initially recommend silicone hydrogel lenses—such as Focus Night and Day (CIBA Vision), Purevision (Bausch + Lomb), Acuvue Oasys (Vistakon), or Biofinity (Coopervision)—to be worn up to a week at a time, in either prescription or plano with the patient’s spectacles worn over the lenses. Not every patient is going to be a candidate for extended wear, so be judicious in your recommendations. As is always the case with extended lens use, educate patients to contact your office immediately if they develop pain, redness or loss of vision.

Patients who report dryness or irritation that is worse in the morning upon awakening may have nocturnal lagophthalmos. Though often not witnessed directly, this is more common than previously thought, occurring in about 10% to 20% of patients.4 Practitioners should monitor blink frequency and quality during the exam, both in and out of the slit lamp; if patients have an incomplete and/or rare blink, it is likely they do not fully close their eyelids at night (figure 2). Treatment for this condition includes nighttime lubricants, such as Celluvisc (Allergan) or ointments, lid taping, sleep masks or goggles and possibly oculoplastic intervention. Nocturnal lagophthalmos is also associated with recurrent corneal erosion, and these patients can benefit from sodium chloride drops or ointment.5 Oculoplastic surgery may also be necessary for other eyelid conditions, such as ectropion, entropion and lid laxity to achieve an optimum contact lens fit.

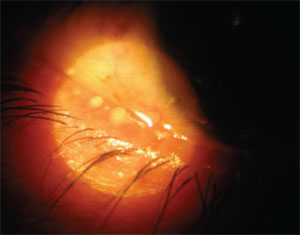

3. Posterior blepharitis as evidenced by thickened secretion upon expression of the meibomian glands.

• Blepharitis or meibomian gland dysfunction. Blepharitis is classified into anterior (anterior lids, lashes and adnexa) and posterior (meibomian glands) forms. If the posterior blepharitis disease is chronic, it is termed meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD). MGD has a prevalence of between 39% and 50%.6,7 Estimates of patients who present to eye care practitioners with blepharitis are as high as 47% (figure 3).8

MGD is typically treated with hot compresses of the lid margins with lid massage and sterile lid wipes. Topical antibiotic drops and ointments, antibiotic-steroid combination drops and oral antibiotics have all been utilized with varying degrees of success.6 Oral doxycycline—though classified as an antibiotic—has important anti-inflammatory properties that perform well with MGD. Some patients suffer from gastrointestinal upset and photosensitivity, and this drug should be avoided in children or women who are pregnant or nursing. Some of these side effects can be offset by using lower doses, such as 20mg doxycycline, which is available as Alodox (Ocusoft) or Periostat (CollaGenex Pharmaceuticals), and 40mg forms such as Oracea (CollaGenex Pharmaceuticals). There are important drug-drug interactions to be aware of with doxycycline. It may enhance the activity of warfarin (Coumadin), causing excessive thinning of the blood, thus necessitating a reduction in the dose of warfarin. Furthermore, phenytoin (Dilantin), carbamazepine (Tegretol), and barbiturates (such as phenobarbital) may enhance the metabolism of doxycycline thus making it less effective.9 Other practitioners advocate the use of minocycline to mitigate these adverse events; however, minocycline treatment has been associated with skin pigmentation changes following dermal treatment and treatment of the thyroid gland.10,11 Doxycycline eye drops can be compounded at specialty pharmacies and have been shown to be beneficial in the treatment of OSD.12

Still other options that can be utilized include Restasis and AzaSite (azithromycin 1%, Inspire Pharmaceuticals).13-15 The use of both of these products implies an “off-label” indication, so the practitioner must have a candid discussion with the patient that is well documented in the chart. Dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids have been shown to be beneficial in the treatment of surface disease due to their anti-inflammatory properties.16,17

Addressing issues relating to allergy, dry eye, ocular surface disease and lid position improves the ocular environment for contact lens use. Assuming the patient’s corneal environment has been optimized, it’s now time to consider lens options.

Soft Lens Candidates

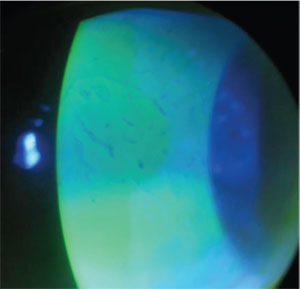

4. Epithelial basement membrane

degeneration at the apex of keratoconus in a patient who had difficulty

wearing primary RGPs for more than three hours and experienced chronic

erosions. He was subsequently refit with soft lens/ GP piggy back,

resulting in longer wearing times and decreased erosions and pain.

Patients with recurrent corneal erosion (RCE) and corneal bullae may benefit from using soft lenses short term. RCE encompasses painful erosions resulting from anterior and stromal corneal dystrophies, such as epithelial basement membrane, lattice, granular and corneal fleck, as well as secondary to trauma (figure 4). This condition can be ameliorated with the temporary use of a bandage soft contact lens along with antibiosis and cycloplegia, as indicated. Corneal bullae can also be managed with bandage contact lenses.

Patients with the following conditions may do well with soft lenses on a long-term basis:

• Dry eye is a major complication associated with graft versus host disease (GVHD), affecting 50% of patients with allogeneic bone marrow transplants.18-20 Bandage contact lenses used daily or on an extended wear basis can provide symptomatic relief of the severe keratitis.

• Superior limbal keratotoconjunctivitis (SLK) is characterized by inflammation of the upper palpebral and superior bulbar conjunctiva, keratinization of the superior limbus and corneal and conjunctival filaments. It may be associated with other diseases, such as keratoconjunctivitis sicca, hyperthyroidism and hyperparathyroidism. The typical patient with superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (SLK) is a woman between 20 and 60 years of age. In such patients, a bandage contact lens may protect the superior limbus from the mechanical friction associated with blinking and reduce the tactile corneal reflex.21

• Many patients suffering from such conditions as Sjögren’s, systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis are unable to wear contact lenses; ironically, for others, lens wear is the only way they can achieve visual comfort, decreased keratitis and improved visual acuity, though vigilant monitoring for complications is required.22,23

• Patients with aniridia, dense corneal scarring from trauma, band keratopathy or surgery often use a prosthetic contact lens for improved cosmesis and to decrease photophobia (figure 5).

GP Lens Candidates

5. This patient has a dense

corneal scar near the visual axis. Resulting irregular astigmatism,

choroidal rupture and obvious ocular disfigurement necessitated the

wearing of a soft cosmetic lens.

Patients with corneal disorders, such as keratoconus, pellucid marginal degeneration, keratoglobus, corneal dystrophies and degenerations, as well as post-refractive surgery, post-penetrating keratoplasty and post-trauma patients, all depend upon gas-permeable lens wear for optimal vision and to reduce the impact of irregular astigmatism (This includes newer scleral and hybrid lens designs). GVHD and Stevens-Johnson syndrome are particularly amenable to treatment with scleral lenses. Benefits of wearing scleral lenses for these disease processes have been described in the literature, including improvement of visual acuity and in corneal signs and symptoms.24-26

Much More Than a Substitute

Contact lenses are much more than a mere alternative to spectacles; they serve an essential purpose for patients with various ocular and systemic conditions. While the treatment of ocular allergy or dry eye might seem tedious, it is powerful to realize the impact that modulating these processes can have on the success of a contact lens fitting. These conditions share the common thread of inflammation, which can be exacerbated by lens wear, so it makes good clinical sense to minimize the amount of surface inflammation a patient presents with in order to maximize their lens wearing experience. Many patients in our practices depend on their lenses for optimal visual improvement, ocular comfort or improved cosmesis for a diseased or disfigured eye. It starts with good clinical observations and a careful and well-thought game plan. Your patients will see the difference!

Dr. Chaglasian is an associate at The Mack Eye Center, a cornea referral practice, in Hoffman Estates, Ill. Prior to that, she was an Associate Professor at the Illinois College of Optometry. Dr. Russell is in group practice with the Marrietta Eye Clinic in Georgia. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry and a diplomate in the Cornea and Contact Lens Section.

1. Yeniad B, Alparslan N, Akarcay K. Eye rubbing as an apparent cause of keratoconus. Cornea. 2009 May;28(4):477-9.

2. Waller EA, Bendel RE, Kaplan J. Sleep disorders and the eye. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008 Nov;83(11):1251-61.

3. Ezra DG, Beaconsfield M, Collin R. Floppy eyelid syndrome: Stretching the limits. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010 Jan-Feb;55(1):35-46.

4. Latkany RL, Lock B, Speaker M. Nocturnal lagophthalmos: an overview and classification. Ocul Surf. 2006 Jan;4(1):44-53.

5. Sturrock GD Nocturnal lagophthalmos and recurrent erosion. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976 February; 60(2): 97–103.

6. Jackson WB. Blepharitis: current strategies for diagnosis and management. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008 Apr;43(2):170-9.

7. Joffre C, Souchier M, Gregoire S, et al. Differences in meibomian fatty acid composition in patients with meibomian gland dysfunction and aqueous-deficient dry eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008 Jan;92(1):116-9.

8. Lemp MA, Nichols KK. Blepharitis in the United States 2009: a survey-based perspective on prevalence and treatment. Ocul Surf. 2009 Apr;7(2 Suppl):S1-S14.

9. Medicinenet.com. Medications and drugs. Available at: www.medicinenet.com/doxycycline/article.htm. (Accessed January 2010).

10. Ozog DM, Gogstetter DS, Scott G, Gaspari AA. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation in patients with pemphigus and pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2000 Sep;136(9):1133-8.

11. Hanzlick R, Wilson R. Minocycline-related black thyroid. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 1988 Sept;9 (3):201-2.

12. De Paiva, CS, Corrales RM, Villarreal AL, et al. Apical corneal carrier disruption in experimental murine dry eye is abrogated by methylprednisolone and doxycycline. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2847-56.

13. Solomon, KD. New drop aimed at lid margin disease. Ophthalmology Management. 2008 Apr(4):72-4.

14. Foulks GN, Borchman D, Yappert CM. Modification of Meibomian Gland Lipids by Azithromycin. Poster. ARVO. 2009.

15. Perry HD, Doshi-Carnevale S, Donnenfeld ED, et al. Efficacy of commercially available topical cyclosporine A 0.05% in the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2006 Feb;25(2):171-5.

16. Macsai MS. The role of omega-3 dietary supplementation in blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction (an AOS thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2008;106:336-56.

17. Boerner CF. Dry eye successfully treated with oral flaxseed oil. Ocular Surg News. 2000 Oct;15:147–8.

18. Jabs DA, Hirst LW, Green WR, et al. The eye in bone marrow transplantation. II. Histopathol Arch Ophthalmol. 1983 Apr;101(4):585-90.

19. Jack MK, Jack GM, Sale GE, et al. Ocular manifestations of graft-v-host disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983 Jul;101(7):1080-4.

20. Russo PA, Bouchard CS, Galasso JM. Extended-wear silicone hydrogel soft contact lenses in the management of moderate to severe dry eye signs and symptoms secondary to graft-versus-host disease. Eye Contact Lens. 2007 May;33(3):144-7.

21. Watson S, Tullo AB, Carley F. Treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis with a unilateral bandage contact lens. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002 April;86(4):485-6.

22. Lemp MA, Bielory L. Contact lenses and associated anterior segment disorders: dry eye disease, blepharitis, and allergy. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2008;28:105-17.

23. Fox RI, Izuno G, Willems J, et al. Sjogren’s Syndrome: A guide for the patient. Available at: www.myalgia.com. (Accessed January 2010).

24. Schornack MM, Baratz KH, Patel SV, Maguire LJ.Jupiter scleral lenses in the management of chronic graft versus host disease. Eye Contact Lens. 2008 Nov;34(6):302-5.

25. Jacobs DS. Update on scleral lenses. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008 Jul;19(4):298-301.

26. Pullum KW, Whiting MA, Buckley RJ. Scleral contact lenses: the expanding role. Cornea. 2005 Apr;24(3):269-77.