|

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can affect the anterior cornea in a wide variety of patterns. Dendritic disease sets up the cornea for the many manifestations of inflammatory herpes stromal keratitis (HSK). However, once dendritic disease has occurred, the posterior cornea may just as easily become involved. The posterior cornea is a big target and its involvement presents so differently from its anterior cornea counterpart that if you only consider HSV keratitis as dendritic keratitis, you may miss the diagnosis of HSV endotheliitis. Here is a closer look at HSV endotheliitis, a clinical entity that may seem completely distinct from dendritic HSV or HSK but often follows similar rules.

HSV Endotheliitis Defined

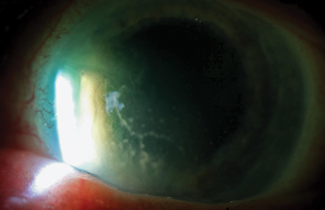

Since herpetic endotheliitis may be foreign to some ODs in the trenches, here is its definition: herpetic endotheliitis is an attack on the corneal endothelium precipitated by a corneal herpes infection. As with HSK, a previous episode of dendritic keratitis is speculated to be a necessary precursor, but sometimes there is no history available in clinic. While HSK is presumed to be a non-infectious inflammation of the stroma secondary to previous epithelial infection, herpetic endotheliitis is a bit more nebulous. Though research shows it responds well to topical corticosteroid, live virus has been isolated in histologic studies from the endothelium in involved eyes.1 A 1999 classification system includes a few variations of HSV endotheliitis, but the one linking presentation is unusual distribution of keratic precipitates (KP) behind zones of edema.2 Depending on the presentation, however, KP may or may not be visible.

|

| This resolving corneal edema has keratic precipitates directly behind it. |

Case Example

Consider the following example. A 50-year-old contact lens wearer presents with concerns of a sore left eye and blurry vision that developed three days earlier and has been getting worse even after discontinuing lens wear two days earlier. Vision is reduced to 20/400 with no improvement with pinhole. You can see from across the room that the patient’s eye is red. Given the history and general appearance, you would be justified in thinking of this as a possible microbial case. However, when you look closer, you see 2+ injection, diffuse epithelial and stromal edema, intraocular pressure (IOP) of 20mm Hg and absence of ulceration despite the initial concerns of a microbial source. Because there is no infiltrate or ulcer, the only remote possibility for microbial keratitis would be Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK). In its early stages, AK does not have ulceration, but it would be uncommon for AK to generate this level of edema, and we’d also expect a well-defined zone of epitheliopathy, so it almost certainly isn’t AK either.

Here, the diagnostic key is the corneal edema. The general differential for an eye without surgical or traumatic history displaying sudden onset corneal edema is brief: viral keratitis, contact lens induced hypoxia, a sudden dramatic spike in IOP (either from Posner Schlossman or acute angle-closure glaucoma) and corneal hydrops.

Of this group, we can rule out IOP, because, although epithelial edema is frequently paired with elevated IOP, much higher pressures than 20mm Hg are generally needed to cause edema. It should be noted that most cases of corneal edema primarily show stromal edema at first, and only into chronicity does prominent epithelial edema develop. Severe IOP spikes, viral endotheliitis and allograft rejection are exceptions that often show epithelial edema acutely.

Another possibility in this case would be hypoxic stress from contact lens use; but here, the patient’s symptoms have continued to worsen despite contact lens discontinuation two days earlier. In most cases, contact lens-related edema shows improvement relatively quickly after lens discontinuation.

Finally, corneal hydrops only occurs in advanced keratoectasia with distortion of the corneal curve that should be plain on slit lamp exam.

That brings us to a likely diagnosis of HSV, which is always one of the primary differentials for an eye with sudden corneal edema. Though nomenclature varies somewhat across the globe, this specific form of HSV is often referred to as disciform endotheliitis. Though the term disciform suggests a localized circular pattern of edema, it may be generalized across the entire cornea, with the central cornea having the greatest involvement. Mid-sized granulomatous KP, while almost always present, are typically obscured by corneal edema early in the process and only unveiled as the edema clears. These are most heavily distributed behind the zones of greatest edema, usually in a circular distribution. Also typical of these cases is an anterior chamber reaction that becomes visible with clearing of edema and the possibility of moderately elevated IOP from trabeculitis.

In this case example, because the patient already discontinued contact lens wear to no effect, the next step is the standard treatment for all non-dendritic HSV keratitis: an antiviral (in this case, oral is preferable given the penetration concerns) and a topical corticosteroid. The patient’s eye will respond quickly to this, though total clearing of edema may take several weeks. In severe or recurrent cases, this treatment may actually lead to corneal endothelial decompensation and require an endothelial transplant.

|

| Here is an example of severe linear endotheliitis. This branching lesion is a single contiguous KP on the endothelium. |

Diffuse and Linear Endotheliitis

Though disciform endotheliitis tends to be the most common form of herpetic endotheliitis, diffuse and linear endotheliitis are other possibilities.1,2 These forms will also have corneal edema, but the initial edema is less profound. In general, any eye with an unusual pattern of KP unilaterally should have HSV on the differential.

Here, “unusual” bears some defining. In most cases of endotheliitis or iritis, KP, particularly if they are granulomatous, are distributed along with convection currents in a pattern known as Arlt’s triangle. Herpetic KP typically fall outside of this triangle. In diffuse endotheliitis, the distribution of KP is widely spread across the corneal endothelium. These tend to be small to moderate granulomatous lesions but may aggregate in severe disease into a retro-corneal plaque.

Alternately, herpetic KP may be distributed as a solid line, sometimes with branching extensions. This is known as linear endotheliitis. It is the most severe form of HSV endothelial disease and also the most difficult form to treat.

Coexisting iritis and trabeculitis are possible with all types of HSV endothelial disease. The differential diagnosis in diffuse endotheliitis is Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis (FHI), anterior extension of toxoplasmosis choroiditis, herpes zoster endotheliitis and some forms of corneal graft rejection. In FHI, KP is prominently stellate, heterochromia is often present and patients are typically asymptomatic of mild iritis. Unlike herpetic endotheliitis, FHI patients do not develop corneal edema. The differential for linear endotheliitis is almost always viral (HSV vs. cytomegalovirus), with an exception for Khodadoust’s line, which can be seen in endothelial graft rejection.

So far, in this column series on HSV, I’ve stated, “any unilateral keratitis without a compelling history is HSV unless proven otherwise,” which seems at first perhaps too sweeping. As we’ve moved along, however, to HSK and now endotheliitis, you can see that the original statement isn’t complete hyperbole. I believe you will never be criticized for treating any unilateral keratitis without a history or clinical picture of microbial disease as HSV. Of course if it doesn’t respond, revisit your diagnosis, but it’s always a reasonable starting point.

1. Holland EJ, Brilakis HS, Schwartz GS. Herpes simplex keratitis. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, eds. Cornea. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2004:1043-74.

2. Holland EJ, Schwartz GS. Classification of herpes simplex virus keratitis. Cornea. 1999;18:144-55.