An effective solution to presbyopia is the brass ring that eye care practitioners and manufacturers have been reaching for our entire careers. While many patients are content to wear spectacles or contact lenses, increasingly our patients seek a more natural and persistent correction, one that feels akin to the vision they remember from their younger years. By 2020, the global number of presbyopes is expected to rise to 1.4 billion.1 Because these patients have a variety of other eye issues such as cataracts, macular degeneration, glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy, our practices will be busier than ever.

Our patients are working much later in life than generations past and using digital devices at high rates, so the visual demands of the older population are greater than ever before. Even in retired patients, near vision demands have never been greater. On top of this, today’s presbyopes want to maintain a youthful appearance, leading to a race among manufacturers to provide more permanent options to correct near vision than conventional glasses or contact lenses.

Many feel traditional surgical options are too invasive, do not consistently produce high quality vision and could potentially cause optical and visual distortions as well as other complications.2 Monovision has been the most common surgical correction for presbyopia to date, performed using laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) or photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) as part of a correction for refractive error. These have their drawbacks, however.

In my practice, I have found the most common complaint associated with monovision is slight distance blur. Moreover, most patients cannot tolerate too much of a difference between their two eyes, limiting the amount of near correction practitioners can provide. Presbyopic LASIK, and multifocal LASIK techniques more specifically, have yielded poor results and most surgeons no longer use them.

The shortcomings of current techniques have made many doctors skeptical of any new technique for presbyopia correction. Despite this, several newly approved options show potential to earn back their trust. Although practitioners have been hesitant to mention new techniques to their patients, this mindset could be problematic. If a patient learns about a new technology from a friend or “Doctor Google,” they may assume you don’t know about the technology and seek out their friend’s practitioner for information. For this reason, it is always advisable to educate patients about new technologies and explain the benefits and risks if they are interested.

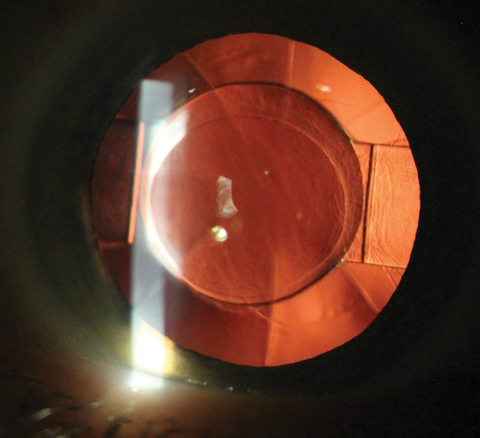

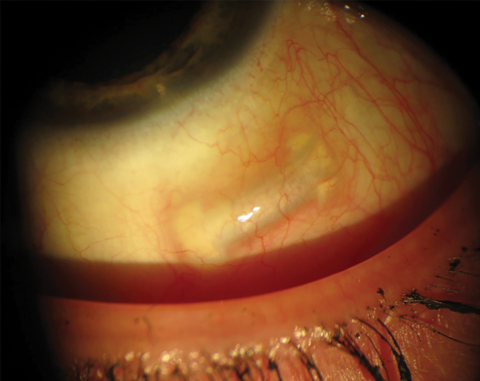

|

| Fig. 1. The Crystalens AO accommodating IOL avoids the glare and halos of multifocals. Photo: Justin Schweitzer, OD |

Intraocular Lenses

For two decades, cataract patients have had the option to choose an intraocular lens (IOL) implant that not only remedies their aphakia but also improves near vision. The category has yet to achieve mainstream success, however, mostly due to concerns about glare, halos and inadequate near vision correction. But properly educated patients with realistic expectations can come away with greater visual independence that translates into satisfaction with the experience.

This option has also become a beneficial alternative for older presbyopes and higher hyperopes. While many feel IOL implantation in the absence of cataracts is too invasive, more surgeons are talking to patients 55 years and older about clear lens extraction, in which the crystalline lens is removed before there are sufficient changes for the patient to qualify for covered cataract surgery.3

In our practice, we typically offer clear lens extraction as well as LASIK or PRK to these patients. Here, it is important to review the pros and cons of each option with patients and make sure they understand that if they have LASIK at this age, the lens will change over time. IOLs also open patients up to options for multifocal, extended depth of focus or accommodating lenses, providing some amount of near vision. Three types of IOLs are used today:

Multifocal IOLs create several focal points with concentric zones of varying optical power.4 Since the aperture of each zone differs, image quality depends on pupil size and reactivity to light and accommodation. Multifocal IOLs, which now can include a toric option, are growing in popularity and new, lower-add multifocal lenses help reduce the size of potential halos. These IOLs are often better tolerated than older generations with 4D-add lenses and thus far have shown success in our practice.

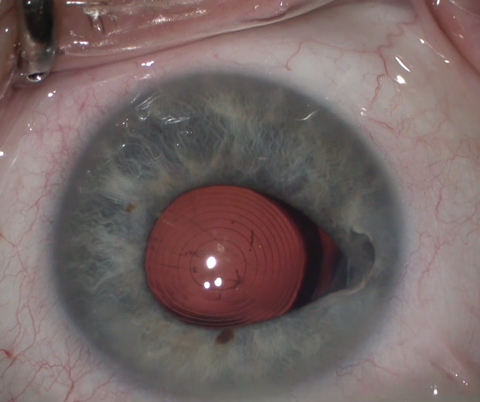

Extended depth of focus IOLs, a new category, seek to overcome the shortcomings of multifocal IOLs by using diffractive optics to elongate the focal length and correct for chromatic aberration (the light dispersion that occurs between colors of different wavelengths). The aim is to improve near and intermediate vision while reducing the likelihood of glare and halos.

Accommodating IOLs attempt to mimic the reshaping of the crystalline lens. This eliminates the risk of glare and halos that may accompany multifocal or diffractive optics, but creates its own shortcomings such as inadequate near vision and the general difficulty of replicating a dynamic physical process.

|

| Fig. 2. The Symfony IOL uses refractive echelettes that appear similar to the concentric rings of a multifocal but diffract rather than split the light entering the eye. Photo: Derek Cunningham, OD, and Walter Whitley, OD |

One commonly used example of an accommodating IOL is the Crystalens AO (Bausch + Lomb) (Figure 1). In theory, the lens moves back and forth to add near power. However, many feel that the lens actually flexes slightly to create a near effect. In our practice, we have found that we can typically achieve about 1D to 1.5D of near power when using this option.

Accommodating designs fall into two categories:

• Single-optic IOLs alter image focal points through anterior movement of the IOL and changes in the lens architecture.4

• Dual-optic IOLs use two lenses to enhance the range of accommodation: an anterior high plus lens coupled with a posterior minus lens. As the distance between the two lenses changes, optical power is altered.4

New and Emerging IOL Options

The Tecnis Symfony IOL (Abbott Medical Optics) has gained wide acceptance in the United States over the past year. It uses an extended range of focus to achieve good distance and intermediate vision, as well as some near (Figure 2). Another option, the Restor 2.5D (Alcon) multifocal lens with active focus, provides similar vision to the Tecnis Symfony IOL. Additionally, both companies have higher-powered IOLs for better near vision with slightly less intermediate vision, although these have also shown a higher rate of associated patient symptoms such as glare and halos. These lenses now are also available in a wide range of astigmatic powers.

Other options for these patients are bioptic procedures, in which the surgeon combines an IOL with LASIK to correct for residual astigmatism. However, one issue with bioptics is that many cataract surgeons do not have access to a laser, forcing them to charge patients a significant amount beyond the standard cataract procedure cost.

The Light Adjustable Lens (RxSight) is the latest entry into the premium IOL market. While its current form does not address presbyopia, its technology could be used to help presbyopes in the future.

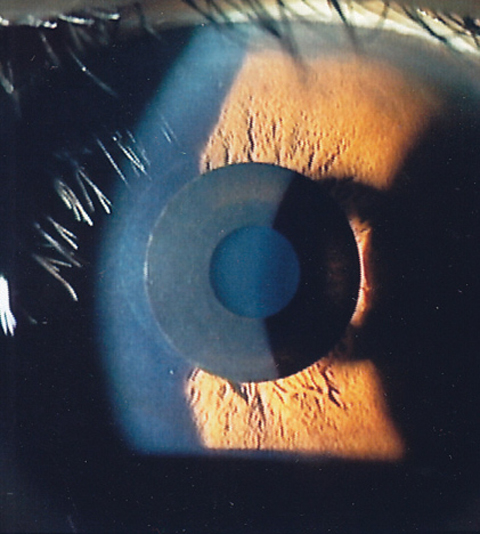

|

| Fig. 3. The Kamra Near Vision Inlay is designed to increase depth of field and improve near vision. Photo: Minoru Tomita, MD |

This lens is implanted in a fairly simple surgical procedure that does not need to employ intraoperative aberrometry, as with some premium IOL implants. With a special laser, the practitioner can adjust the power of the IOL after surgery, leading to more accurate postoperative refractive outcomes. Its initial approval covers astigmatism up to 0.75D. Because ultraviolet (UV) light is used to adjust the lens power until the final power is permanently set, patients must avoid any exposure to UV light in the immediate postoperative period or the lens will not be adjustable.

In the future, this lens could open up post-surgery optic adjustments for many types of patients, including coverage of greater astigmatism and multifocal designs. For example, if a patient were unhappy with their multifocal effect, practitioners would be able to adjust the optics to a more acceptable design after surgery.

Corneal Inlays

First approved in the US in 2015, corneal inlays have several advantages over other refractive procedures.5 They are an additive technology that can be removed in the event of patient dissatisfaction, complication or onset of other conditions. The procedure does not remove tissue, so patients can still potentially undergo future surgical solutions. In fact, the procedure is considered less invasive than lens surgery. And depending on the inlay, near correction often remains effective as presbyopia advances.

Three styles of corneal inlays exist, all designed for monocular implantation in the non-dominant eye: corneal reshaping inlays, refractive inlays and small-aperture inlays. Currently, two corneal inlays have been FDA approved, but one of those companies recently went out of business, leaving only one on the market. Additionally, a third corneal inlay option is in Phase III trials and a fourth is in development.

Kamra Near Vision Inlay (AcuFocus). This small-aperture (5µm) inlay is placed in a pocket in the stroma to increase depth of field and improve near vision while only minimally impacting distance vision (Figure 3).6 The opaque ring is 3.8mm wide with a 1.6mm aperture, and the inlay—which houses 8,400 laser holes to improve oxygen and nutrient transfer through the cornea—is placed in the non-dominant eye. Near light rays coming through the pinhole are focused clearly on the retina. As a result of this process, distance vision is often slightly decreased, typically by two to three lines. If a patient is unhappy with their results, the surgeon can remove the inlay and vision should return to close to what it was before the procedure.

The Kamra is indicated for presbyopic patients between the ages of 45 and 60 with cycloplegic refractive spherical equivalents of +0.50D to -0.75D and ≤0.75D of refractive cylinder. These patients do not need glasses or contact lenses for clear distance vision, but for near correction they require +1.00D to +2.50D of reading add. The ideal patient has slight myopia but good distance vision.

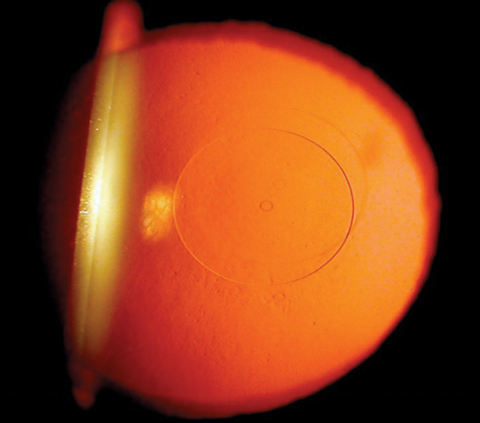

|

| Fig. 4. The Flexivue Microlens, which is currently in FDA trials, functions similar to a multifocal contact lens, using concentric rings of increasing add power. Photo: Clark Chang, OD |

Flexivue Microlens (Presbia). Currently in Phase III FDA trials, this hydrophilic acrylic refractive inlay has a 3mm diameter, 0.015mm/15µm edge thickness and a plano central zone with increasing rings of higher power (Figure 4). It functions similarly to a multifocal contact lens and comes in powers ranging from +1.5D to +3.5D in 0.25D increments. The lens is inserted under a flap or in a pocket in the non-dominant eye, and the surgeon can remove and replace it with a higher power inlay as the patient becomes more presbyopic.

Icolens (Neoptics). Still in the early stages of development, this hydrophilic copolymer inlay is 3mm in diameter and has an edge thickness of <15µm (depending on refraction). For presbyopia, it offers powers ranging from +1.5D to +3D in 0.5D steps. Since it has no power in the center and positive refractive power in the periphery, powers can be exchanged as presbyopia progresses.

Raindrop Near Vision Inlay (ReVision Optics). Although this corneal reshaping inlay was approved by the FDA in June 2016, ReVision Optics announced in January 2018 that it was closing its doors, taking the Raindrop off the market.8 This came as a result of poor sales and insufficient funding.

In general, the inlay market has yet to meet sales expectations, at least in part because surgeons have not embraced the technology. For this category to continue moving forward, more surgeons will need to start incorporating this technology into their practices and testing the benefits.

Scleral Inserts

A new concept entails inserting bands in the sclera to increase tension on the zonules in hopes of preserving the patient’s accommodative ability. As we age, the crystalline lens increases in size, limiting the amount of tension the ciliary muscle can create to change the eye’s focus.

|

| Fig. 5. The VisAbility represents a new concept in presbyopic surgery: scleral inserts. It is currently undergoing FDA trials. Photo: Refocus Group |

The VisAbility Micro-Insert (Refocus Group) places four PMMA inserts into the sclera just beyond the limbus; FDA trials are underway (Figure 5). By increasing the space between the lens and ciliary body, this procedure improves the ciliary muscle’s ability to refocus the natural lens. This procedure would be targeted for emmetropes and may end up being combined with another procedure to first correct a patient’s distance vision.

Succeed Now

The perfect solution to presbyopia still eludes us. But thanks to the wide array of technologies currently available, we can help satisfy many people today. Educating our patients and knowing how they use their eyes is paramount to success. Too often, we judge success as sharp 20/20 vision, but with refractive surgery many patients are better off if we aim for 20/happy. We need to change our thinking so we can find the best available solutions for our patients.

Patients with a long history of multifocal contact lens wear are generally good candidates for a clear lens extraction with one of the new IOLs available, and cataract patients are better served by today’s lenses as well. Patients who are close to emmetropia but can adjust to slight monovision could be good corneal inlay candidates. Those who cannot tolerate any blur might be good VisAbility implant patients.

Surgical correction of presbyopia in 2018 is more robust than ever, and motivated patients can achieve success. However, always be sure to under-promise and over-deliver.

Dr. Geffen is the director of Optometric and Refractive Services at the Gordon Schanzlin New Vision Institute of TLC Laser Eye Centers in San Diego, California. He is the current past president for the Optometric Cornea and Cataract Refractive Society.

1. Frick KD, Joy SM, Wilson DA, et al. The global burden of potential productivity loss from uncorrected presbyopia. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(8):1706-10. |