|

Corneal hydrops, an uncommon complication seen in patients with corneal ectatic disorders, is characterized by the leakage of aqueous through a tear in Descemet’s membrane, which leads to a rolling of the edge and subsequent gaping of the posterior surface of the cornea. This allows the aqueous fluid to intrude into the cornea, producing an acute edematous response, relative changes in corneal architecture and clinical symptomatology. Patients typically present with a rapid decrease in visual acuity, photophobia and pain. There is also notable localized edema and, in some instances, visible ectasia in the areas most compromised.

Corneal hydrops is estimated to occur in 2% to 3% of patients with keratoconus, with the majority presenting between ages 20 and 40. While some literature supports an increased rate of occurrence in males, there is no notable prevalence by race. In most cases, the location of the hydrops is inferior to the apex of the cone. When questioned, patients frequently admit to significant eye rubbing. In some instances, severe coughing and/or heavy lifting have also been associated with onset of disease. Down’s syndrome may be a risk as well.

Most cases heal naturally over a period of several months when treated using conservative methods, which include topical cycloplegic agents, corticosteroids to reduce inflammation and IOP-lowering drugs. Some patients, however, may require surgery if corneal edema persists or resultant corneal scarring affects visual clarity.

| |

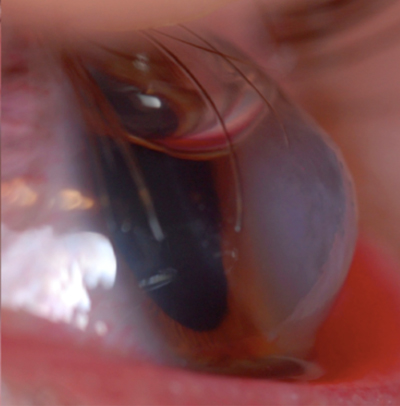

| Fig. 1. Placement of intracameral C3F8 (non-expansile concentration) in a different patient than the one described here. Note: the patient was instructed to lie flat with their eyes looking up towards the ceiling, so that the gas could occlude the break in the posterior cornea. Photo: Edward Boshnick, OD | |

| |

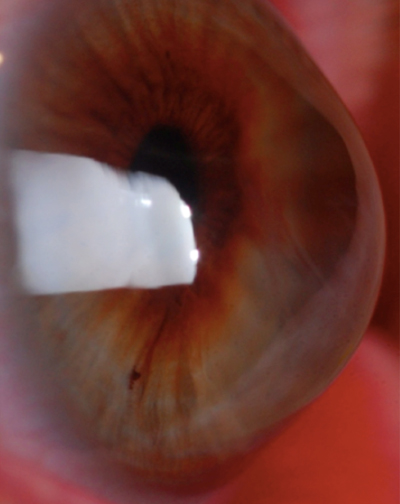

| Fig. 2. Hydrops resolved. Photo: Edward Boshnick, OD |

Conservative medical intervention is usually sufficient to stave off the more concerning consequences of perforation, but overall has little impact on visual outcome or duration of disease. Thus, doctors are turning to other, more advanced methods of disease management. Recently, there has been renewed interest in the use of intracameral SF6 and C3F8 gases, which have been shown to lead to faster improvement compared to more conservative treatments.1,2 Intrastromal venting incisions, used to delimit the large vacuoles that occur in some patients, have also demonstrated some success but are still relatively experimental. Overall, more research is needed on the efficacy of these and other emerging treatments.

Case Study

A recent case of corneal hydrops that presented to my office is emblematic of the conventional characteristics of the disease, and serves as a good example of conservative vs. more aggressive surgical treatment.

TW, a 42-year-old black female, was initially seen for a complaint of progressive change in visual function relative to longstanding keratoconus, and a recent history of possible progression noted by her current clinician. The consultation identified significant apical scarring in her right eye, and notably less scarring in the left. The best-corrected visual acuity with spectacles was 20/300 OD, which did not improve on pinhole, and approximately 20/80 OS with minimal pinhole improvement. Her previous history was positive for contact lens wear, although discomfort as well as poor acuity had decreased the patient’s wearing activity to a minimal level over the last six to 12 months.

The remainder of her examination elements (i.e., intraocular pressure, lenticular assessment and posterior pole) were relatively normal. The patient was advised that several options were available: she could forgo intervention at this time, be fit with a complex hybrid-type or scleral contact lens with the hope of achieving better results than her current standard hard lens, or undergo a corneal transplant.

The patient elected to consider the options and was scheduled for another appointment in three months, with plans to return sooner if a decision was made. Approximately six weeks after her initial evaluation, the patient contacted the on-call service on a weekend and indicated that she had developed a notable decrease in vision, along with severe pain and photophobia.

I saw her on the same day, and it was evident she had a significant corneal hydrops and a visible Descemet’s membrane tear. This was accompanied by notable apical ectasia in the zone of the hydrops. The presentation of the cornea was 3+/4 edema, focally located over the zone of the hydrops, which consisted of epithelial microcystic edema and intrastromal cysts and vacuoles. The diameter of the area was approximately 4.5mm to 5.0mm. Visual acuity was hand motion at two feet with no pinhole improvement.

I discussed treatment options with the patient, who elected to proceed with conservative therapy, which included a topical antibiotic (ciprofloxacin) QID to prevent infection, one drop of a cycloplegic (atropine) BID, the use of a hypertonic saline ointment (Muro 128) QID and an ocular antihypertensive agent to lower pressure and decrease the posterior forces on the cornea contributing to architectural change. The patient was also placed on topical Durezol QID, and a bandage lens was inserted—primarily for comfort, but also to prevent perforation.

The patient was observed over several weeks and, as is typical with hydrops, the intrastromal edema that was present at the initial episode began to resolve, as did the photophobia. At the initial three-day follow-up, the pain had lessened significantly with the atropine and Durezol, and the inflammatory response present in the cornea showed a mild decrease. Additionally, the pressure had been reduced from 16mm Hg to 10mm Hg. The patient’s bandage lens was removed in order to view the corneal surface; upon removal, a decrease in the microcystic edema was observed and the stromal vacuoles and clefts appeared stable. I ordered current medication levels be maintained, but decreased the atropine to QD.

At the two-week follow-up, I reduced the steroids to BID and stopped the atropine. I continued the antibiotics but reduced the dose to BID. The bandage lens was also removed at two weeks and the cornea was competent with a negative Seidel. The patient called two days after the bandage lens was discontinued and indicated that she had developed a foreign body sensation, so I reinstituted lens wear. I maintained her on the antihypertensive agents for approximately four weeks. Additionally, she used the hypertonic saline ointment four times daily throughout the treatment period.

By the fourth week, the patient’s vision had returned to 20/200 best-corrected in the affected eye. Additionally, the microcystic edema had reduced dramatically, and the stromal edema had begun to demonstrate a coalescence of the vacuoles, which were notably present at the initial clinical assessment.

It should be noted in cases like this one that therapeutic options like hybrid or scleral lenses are less viable because of the scar formation, which is almost universal in patients of this type following a severe hydrops. I discussed the potential for a therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty as the option of choice, and TW is actively considering the possibility once the eye stabilizes. I anticipate that, given her current, relatively poor visual rehabilitative potential and the fact that the other eye also shows notable keratoconus, a penetrating keratoplasty would be a reasonable option to rehabilitate visual function and give her overall better visual potential in the years to come.

1. Panda A, Aggarwal A, Madhavi P, et al. Management of acute corneal hydrops secondary to keratoconus with intracameral injection of sulfur hexachloride (SF6). Cornea. 2007;26(9):1067-9.

2. Basu S, Vaddavalli PK, Ramappa M, et al. Intracameral perfluoropropane gas in the treatment of acute corneal hydrops. Am J Ophthalmol 2011:118(5):934-9.