Dry eye disease (DED) is a chronic, multifactorial condition that is one of the most commonly identified diagnoses in eye care. Some studies have found the symptomatic patient population in the United States to be approximately 20 million.1 A recent population-based study found DED among the most identified eye diseases (fifth in females, ninth in males) providing additional epidemiological evidence for DED as a commonly occurring condition driving patients to seek medical care.2

A literature review of contact lens wear and dry eye disease could discourage a clinical practitioner from considering contact lenses for treating ocular surface disease. However, contact lenses are recognized not only for their refractive and aesthetic benefits to patients, but also as medical devices used in the management of ocular disease. DED patients may benefit from using scleral contact lenses.

|

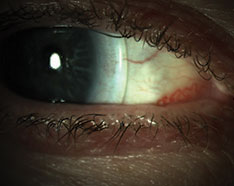

| Fig. 1. Significant superficial punctate keratitis (SPK) prior to scleral lens fit. |

Lens-associated Dryness

The diverse and overlapping etiologies of DED contribute to the condition’s multifactorial nature and complexity of diagnosis and treatment. Sex, changes in hormones, meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), medications (systemic and ophthalmic), ophthalmic surgery, comorbid conditions and poor mechanics (blink mechanism) are among the most common suspects. Additionally, several studies have found contact lens wear to be a significant risk factor for DED. While its prevalence in the general population reportedly ranges from 0.39% to 33.7%, contact lens wearers have been found to experience dry eye symptoms much more frequently.

Approximately 50% of contact lens wearers report dry eye symptoms at least some of the time.2 The same study noted contact lens wearers were 12 times more likely than emmetropes to report dry eye symptoms and five times more likely than spectacle wearers.2 Numerous studies have identified contact lens wear as a potential risk factor for dry eye patients as a trigger to initiate symptoms or to exacerbate existing disease.

Potential origins of contact lens–associated dryness include increased tear film evaporation, increased osmolarity, dewetting of the contact lens related to poor biocompatibility or a combination of these.2 DED in contact lens wearers may contribute to alterations to tear film stability, resulting in desiccating stress to the ocular surface that can manifest in changes in osmolarity and loss of homeostasis.

Sclerals' Benefits

As a practitioner at a tertiary dry eye center, I often make referrals to colleagues for services not performed at the center. The primary referral I make within optometry is to contact lens specialists. I have found increasing opportunity and success in treating recalcitrant dry eye disease with scleral lenses. While most lenses are prescribed for corneal irregularity (74%), a smaller but still valuable group (16%) is prescribed scleral lenses for ocular surface disease.5

The Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) Dry Eye Workshop II (DEWS II) has identified both symptomatic patients for ocular surface disease as well as those with neuropathic pain, or keratoneuralgia, as potential candidates for scleral lens fits.6 Neuropathic pain, or “pain without stain,” is often difficult to treat due to the discordance between signs and symptoms.

Scleral lenses are thought to minimize symptoms by interrupting the pain cycle in some patients. In patients exhibiting signs of ocular surface disease like pigment epithelial defects (PEDs) and filamentary keratitis scleral lenses can provide improvement in both clinical signs and patient comfort.6,7 While soft contact lenses are inexpensive, readily available and prescribed more widely by practitioners, scleral lenses offer a unique environment for non-healing PEDs by creating an oxygenated precorneal fluid reservoir, which allows for continual hydration of the cornea, provides protection from the external environment with little contact to the cornea and provides optimal visual correction.5

Scleral lenses are often a viable option for patients with recalcitrant dry eye when other traditional therapies (artificial tears, autologous serum drops, ophthalmic steroids, cyclosporine, lifitegrast, punctal plugs) fail to provide clinically significant improvement. Lenses may be used alone or as part of a combination therapy with traditional treatments.5

|

| Fig. 2. After the scleral lens fit, the patient reported improvement in dry eye symptoms. |

Case #1

A 69-year old, female was referred to the dry eye center for evaluation and treatment by her ophthalmologist. Her complaints of irritation and fluctuating vision began two or three years ago and were constant. She suspected her ocular discomfort was driven by a poorly fitting rigid gas permeable (GP) contact lens. Her current pair were two years old, and she had worn them comfortably until the last several months. The patient had a history of GP wear for approximately 50 years. In addition to her dry eye complaints, she was also diagnosed with keratoconus (OD<OS) several years prior and reported stability.

The referring doctor prescribed cyclosporine A, 0.05%, ophthalmic emulsion twice daily and use of artificial tears as needed. However, the patient found the drops to burn too much to remain compliant and discontinued after one week of use. Currently, she was exclusively using artificial tears without success.

Her corrected entrance visual acuity was 20/25 OD and 20/30 OS, and her OSDI score was 27. MMP-9 testing was negative. Phenol red thread testing was 23/20 (OD/OS). Meibography revealed moderate gland atrophy in both of the lower lids. Remarkable findings in the physical examination included mild blepharitis (UL/LL), superficial punctate keratitis (SPK, OD<OS) and mild congestion of meibomian gland secretion (Figure 1). The patient’s lid margins had mild telangiectasias and scalloping of the inferior led margin. Her tear break-up time was three seconds in each eye.

The patient was placed on an oral omega supplement. She was encouraged to resume cyclosporine A, 0.05% ophthalmic solution and continue artificial tear use. However, the patient reported she did not prefer to use ophthalmic medications for the management of her dry eye disease. In light of her preference and the pre-existing condition of keratoconus, we referred her for a scleral contact lens fit. Lenses were ordered for the patient, and she returned to the dry eye center in the interim for follow-up at one month. She reported compliance with artificial tears and nutrition supplement. Symptoms and signs persisted similar to initial examination. At follow-up, we provided the patient with an in-office lid hygiene treatment with an okra-based polysaccharide lid hygiene treatment and instructed her to begin the at-home product twice daily.

After a series of lenses, an ideal scleral lens was selected for the patient. She noted good comfort and good vision, and the fitting doctor finalized the prescription. After the finalization, the patient returned to the dry eye center for evaluation after one month of lens wear (Figure 2). Her OSDI decreased from 23 to 2. The patient’s cornea was clear of SPK OD/OS, and her visual acuity was 20/20 (OD/OS).

|

| Fig. 3. Upper and lower lid telangectasias with anterior blepharitis. |

Case #2

A 59-year old Caucasian male presented with the chief complaint of constant dryness and blur in his right eye. The patient’s medical history also included hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis and Type 2 diabetes, all of which he was diagnosed with in 2008. His ocular history included a successful refractive surgery decades prior and current use of spectacles for reading only.

In 2016, the patient was diagnosed with a bacterial ulcer. The bacterial ulcer rapidly worsened under in spite of aggressive treatment by a trained cornea specialist. Cultures revealed the offending bacteria was methicillin-resistant Staphyloccus aureus (MRSA).

The patient was treated with a series of fortified antibiotics as well as amniotic membrane. Within six months a penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) was performed. However, several months post-PKP, the patient suffered a corneal perforation. The perforation was treated and the patient had been stable for several months but continued to suffer from dryness. His current treatment regimen included cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion, 0.05% BID and loteprednol ophthalmic gel BID.

Upon initial exam in the dry eye clinic, visual acuity was 20/600 OD with 20/125 pinhole acuity and 20/20 OS. He presented with bilateral lid scalloping accompanied by telangiectatic vessels and lash debris (Figure 3). Anterior segment evaluation further revealed superficial punctate keratitis on both corneas (OD>OS). The right eye presented with filaments adhered to the cornea and geographic corneal scarring.

We considered treating the filamentary keratitis with amniotic membrane. However, the patient noted a poor experience previously and refused insertion. Instead, we prescribed N-acetylcysteine (NAC) drops to break up the corneal filaments, as well as hypocholorous acid lid hygiene spray and preservative-free hyaluronic acid artificial tears.

|

| Fig. 4. This patient reported good comfort and significant improvement in vision after receiving sclerals. |

The patient returned for follow up two weeks later. At the visit, the filamentary keratitis had resolved. However, as expected, significant SPK remained. We decreased NAC ophthalmic drops to BID; loteprednol, cyclosporine and artificial tears were maintained as directed. We also added an okra-based polysaccharide lid hygiene gel to the patient’s regimen. He was scheduled for scleral lens fit with the expectation to discontinue NAC drops with a successful fit as well as improve the patient’s comfort and decrease his dryness complaint.

We referred the patient to a colleague for scleral lens fitting. He was initially fit in ZenLens with an oblate design. The lens had a 17.0mm diameter and parameters of +8.00-1.00X050. The patient reported no lens discomfort or dryness while wearing. The patient was allowed to wear the lens up to three hours per day until a second lens arrived with revisions (ZenLens Toric PC +7.50/9.7/17.0 with an additional 50 microns of clearance 360 degrees). The second lens provided good central clearance and improved limbal clearance with no blanching. The patient continued to report good comfort and significant improvement in vision with his acuity measured at 20/60+2 and 20/20 OS (Figure 4).

Scleral lens fitting and dry eye management present an opportunity for bidirectional referrals within optometry. Each physician in the equation can benefit from inter-professional referrals. In addition, patients will receive the most comprehensive care for their ocular surface disease.

Dr. Hauser is the director of clinical affairs for Keplr Vision. She specializes in implementation of medical services to the group’s 100+ network of practices across the United States. In addition, Dr. Hauser practices clinical care at The Eye Specialty Group in Memphis, Tenn., where she focuses on ocular surface disease and surgical management. She is the founder of DryEyeCoach.com, the leading peer-to-peer education hub for ocular surface disease, and Signal Ophthalmic Consulting (SOC), which designs premier care plans for optometry and ophthalmology practices with an emphasis on dry eye care and cataract/refractive surgery. Dr. Hauser is a founding member of the Intrepid Eye Society, Theia Award winner and named among the Most Influential Women in Optical. Dr. Hauser is also a proud mother of three children and avid health enthusiast.

| 1. Gayton JL. Etiology, prevalence and treatment of dry eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;3:405-12. 2. Nichols JJ, Sinnott LT. Tear film, contact lens and patient-related factors associated with contact lens-related dry eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(4):1319-28. 3. Chen S, Han T, Huang W. Study of therapeutic bandage type contact lens in the treatment of 27 cases of severe tear and evaporative dry eye. Mod Hosp. 2018;18(5);750-2. 4. Lee YK, Lin YC, Tsai SH, et al. Therapeutic outcomes of combined topical autologous serum eye drops with silicone–hydrogel soft contact lenses in the treatment of corneal persistent epithelial defects: a preliminary study. 2016; 39(6):425-30. 5. Nau CB, Harthan J, Shorter E, et al. Demographic characteristics and prescribing patterns of scleral lens fitters: the SCOPE Study. Eye Contact Lens. 2018; 44(9) Suppl 1:S265-72. 6. Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):276283. 7. Jones L, Downie LE, Korb D, et al. TFOS DEWS II management and therapy report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):575–628. |