Dry eye disease (DED), or keratoconjunctivitis sicca, is one of the most common complaints that eye care practitioners face in their practice.1 In fact, dry eye is the second most common reason patients come in to seek eye care and is typically characterized by symptoms of irritation, including blurred and fluctuating vision, tear film instability, increased tear osmolarity and ocular surface epithelial disease.2-5 Although a frequently seen problem, it is often a challenging clinical issue to identify and diagnose, because it presents differently in each patient.

Dry eye severely impacts your quality of life by decreasing functional vision—which includes the ability to perform daily activities, such as reading, using a computer and driving.6 Signs of dry eye can be evaluated with several diagnostic tests; conjunctival staining with lissamine green or rose bengal, for example, can provide a diagnosis within seconds. Positive staining on these tests indicates that the ocular surface should be improved before embarking on surgery. Other methods to diagnose dry eye include fluorescein corneal staining, Schirmer testing, tear meniscus and debris, and corneal sensation.7

Causes of Inflammation

There is increasing evidence that dry eye is an inflammatory disease; it is related to the inflammation of ocular surface, based on the patient’s immune response and induced by many cytokines.8-11 Cytokines are known to stimulate the nerve endings that mediate pain and itching, and have been identified in the tear film of dry eye disease patients. The presence of these inflammatory mediators on the eye likely accounts for at least some of the burning and itching experienced by the patients. Disease or dysfunction of the tear secretory glands leads to changes in tear composition—such as hyperosmolarity—that stimulate the production of inflammatory mediators on the ocular surface.12 Inflammation may, in turn, cause dysfunction or disappearance of cells responsible for tear secretion or retention.13 Inflammation can also be initiated by chronic irritative stress (e.g., contact lenses) and systemic inflammatory/autoimmune disease (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis). Regardless of the initiating cause, a vicious cycle of inflammation may develop on the ocular surface in dry eye, which will ultimately lead to ocular surface disease.

Hyperosmolarity of the tear fluid has been recognized for decades as a common feature of all types of dry eye, and is referred to as the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of dry eye.14 It is also recognized as a pro-inflammatory stimulus.15,16 Treating inflammation holds promise to address the patients’ symptoms, to calm the ocular surface and restore ocular surface health.

How Steroids Can Help

Artificial tears have long been used as first-line therapy in the treatment of DED. While mild or episodic symptoms are easily controlled with an ocular lubricant, long-term application of artificial tears is not effective for patients with severe symptoms.

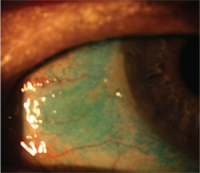

Lissamine green staining of conjunctiva in dry eye disease.

Inflammation seems to be a key pathogenic factor for dry eye. As a result, some patients may continue to complain of eye irritation despite adequate aqueous enhancement therapies without any anti-inflammatory drugs.

Clinical evidence indicates that anti-inflammatory therapies that inhibit inflammatory mediators reduce the signs and symptoms of DED. Corticosteroids are potent anti-inflammatory agents that are routinely used to control inflammation in many organs. Topical corticosteroids are approved by the FDA and prescribed for corticosteroid-responsive inflammatory conditions of the conjunctiva, cornea and anterior globe—including DED.17 In fact, several randomized trials have demonstrated that short-term topical corticosteroid use—as long as four weeks—improves signs and symptoms of DED.17

Additionally, corticosteroids have been reported to decrease ocular irritation symptoms and corneal fluorescein staining and improve filamentary keratitis.18,19 In a retrospective clinical series by Peter Marsh, M.D., and Stephen Pflugfelder, M.D., topical administration of a 1% solution of non-preserved methylprednisolone—given three to four times daily for two weeks to patients with Sjögren’s syndrome KCS—provided moderate to complete relief of symptoms in all patients.19 This therapy was even effective for patients with severe KCS who demonstrated no improvement with maximum aqueous enhancement therapies.19 In a prospective, randomized clinical trial by Maite Sainz de la Maza, M.D., Ph.D., and colleagues, topical treatment of dry eye patients with non-preserved methylprednisolone and punctual plugs significantly decreased the severity of ocular irritation symptoms and corneal fluorescein staining, compared to the group that received punctual occlusion alone.20

There are also a variety of steroids available in eye care. The two traditional groups of agents are the ketone steroids (prednisolone, dexamethasone, fluorometholone, medrysone and rimexolone) and the ester steroid (loteprednol). A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled study of loteprednol etabonate showed that a subset of patients with the most severe inflammatory signs at entry—treated topically with loteprednol—showed a significantly greater decrease in central corneal fluorescein staining scores when compared to its vehicle (31% vs. 0%, respectively).18 There was also a 25% decrease in inferior bulbar conjunctival hyperemia in the loteprenol-treated group compared to a 33% increase in the vehicle-treated group.18 There was no change in intraocular pressure in the steroid treated group. The study showed that patients with at least moderate clinical inflammation were more likely to show significant benefits with loteprednol.18

In another open-label randomized study, KCS patients who received fluorometholone plus artificial tear substitutes experienced lower symptom severity scores, as well as less fluorescein and rose bengal staining, than patients who received either artificial tear substitute alone or artificial tear substitute plus flurbiprofen.21 In one study, steroids rapidly ameliorated the subjective symptoms among the patients with moderate or severe dry eye, while no obvious effects were observed when using artificial tears only.22 Steroids significantly decreased the patient’s complaints within one week. Meanwhile, all detected indices, such as cornea fluorescein staining, tear film break-up time and tear secretion tests, were clearly improved one month after corticosteroid treatment.22

All of these studies suggest that rapid anti-inflammatory activity with corticosteroids is very effective for patients with moderate or severe dry eye. This, in turn, provides evidence that non-specific immune inflammation is involved in the development of dry eye. Although topical corticosteroids are effective, they are generally recommended only for short-term use because prolonged use may result in adverse events including ocular infection, glaucoma and cataracts.

However, corticosteroids may differ in their propensity to cause these complications. For example, some evidence suggests that loteprednol—which is rapidly metabolized to inactive metabolites—may have a better safety profile than other corticosteroids.18 In a summation of randomized studies, treatment with loteprednol etabonate (0.5% concentration) for less than 28 days resulted in a 2% incidence of elevated intraocular pressure, compared with a 7% incidence with prednisolone acetate (1% concentration) and 0.5% incidence with placebo.18

Prescribing the Right Steroid

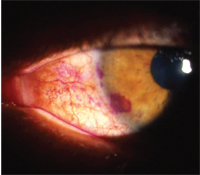

Rose bengal staining in dry eye.

According to Gary Foulks, M.D., of Louisville, Ky., three features determine steroid selection: tolerance, potency and side effects.23 Dry eye patients are much more sensitive to preservatives, so patients may need a drop from a compounding pharmacy without a preservative. Although this limits the drop’s shelf life, is inconvenient and can be expensive, it is valuable for some patients.

Steroids can also have different potencies. For example, dexamethasone is very potent steroid, but doesn’t penetrate ocular tissues well and has a strong side effect profile. In contrast, prednisolone is almost as potent and penetrates ocular tissues well. Other steroids—like loteprednol etabonate and fluorometholone—are less potent and have better safety profiles. The most worrisome steroid side effects are intraocular pressure (IOP) spikes and cataract formation. Compared to dexamethasone and prednisolone, loteprednol and fluorometholone have lower rates of these complications.

Because of the risks of bacterial or fungal infection following prolonged steroid exposure, steroids are typically used only for one to two weeks in dry eye patients. This limited steroid use is contraindicated in patients who demonstrate an increase in intraocular pressure in response to these drugs. Cataract formation is also a well-recognized adverse effect of topical steroids.

An Alternative Treatment

As an alternative to steroids—or as an adjunctive therapy—topical cyclosporine can also be used to control inflammation in dry eye disease. While cyclosporine does not demonstrate the rapid anti-inflammatory effect of steroids, it carries fewer risks and is safe for long-term use.

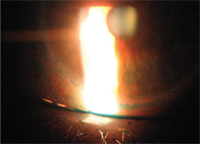

Decreased tear meniscus in dry eye.

Because of their complementary efficacy and safety profiles, many practitioners often begin dry eye treatment by prescribing both topical steroids and cyclosporine. Following the recommendation of the Asclepius Panel, the use of combination therapy is instituted with the topical corticosteroid, Lotemax (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension 0.5%, Bausch + Lomb) and Restasis (cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05%, Allergan).24 The Asclepius Panel recommends practitioners begin early treatment with an anti-inflammatory agent (such as Lotemax) four times a day to improve symptoms and to prevent disease progression. After two weeks, the frequency of the corticosteroid is reduced to twice daily and supplemented with Restasis twice a day. Treatment with loteprednol was stopped after day 60, while cyclosporine treatment is continued.

Thereafter, patients should continue this therapy and increase Lotemax dosage during acute flare-ups.25 Lotemax provides more immediate control of the inflammatory process and may increase patient adherence to the regimen by alleviating the burning that can be associated with cyclosporine. In this way, the patient gains an immediate anti-inflammatory effect from the steroid and long-term control of inflammation from the cyclosporine. Combined immunomodulation using cyclosporine and loteprednol, which act on different steps in the inflammation cascade, should work faster and more effectively than use of the drugs separately as monotherapy.

The Future of Dry Eye

Dry eye is related to inflammation of the ocular surface, and immune-mediated inflammation plays an important pathogenic role. Corticosteroids are effective anti-inflammatory drugs that can rapidly and effectively relieve the symptoms and signs of moderate or severe dry eye. When analyzed collectively, the aforementioned studies indicate that topical corticosteroids are an important tool in the management of dry eye. While no steroid-related complications were observed in the short-term clinical trials, there is potential for toxicity with long-term use including an increase of intraocular pressure and cataracts. Such risks may limit the use of more potent steroids for chronic therapy of dry eye. The risk-benefit ratio may be better with soft steroids that have less intraocular activity and a lower likelihood of raising intraocular pressure, such as fluorometholone and loteprednol etabonate.

Dr. Bowling is in private group practice in Tuscaloosa, Ala. He is also a diplomate in the Primary Care Section of the American Academy of Optometry.

Dr. Russell is in group practice with the Marietta Eye Clinic in Georgia. He is a diplomate in the Section on Cornea, Contact Lenses and Refractive Technologies of the American Academy of Optometry.

1. Schaumberg DA, Sullivan DA, Buring JE, Dana MR. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome among US women. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003 Aug;136:318-26.

2. Pflugfelder SC, Tseng SC, Sanabria O, et al. Evaluation of subjective assessments and objective diagnostic tests for diagnosing tear-film disorders known to cause ocular irritation. Cornea. 1998 Jan;17(1):38-56.

3. Musch DC, Sugar A, Meyer RF. Demographic and predisposing factors in corneal ulceration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983 Oct;101(10):1545-8.

4. De Paiva CS, Lindsey JL, Pflugfelder SC. Assessing the severity of keratitis sicca with videokeratoscopic indices. Ophthalmology. 2003 Jun;110(6):1102-9.

5. Goto E, Yagi Y, Matsumoto Y, Tsubota K. Impaired functional visual acuity of dry eye patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002 Feb;133(2):181-6.

6. Miljanoviæ B, Dana R, Sullivan DA, Schaumber DA. Impact of dry eye syndrome on vision-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007 Mar;143(3): 409-15.

7. Donnenfield ED. Ocular Surface Management for the Cataract and Refractive Surgeon. Ocular Surgery News. 2009 Jun 25. Available at:

www.osnsupersite.com/view.aspx?rid=41659 (Accessed November 2010).

8. Stern ME, Beuerman RW, Fox RI, et al. The pathology of dry eye: the interaction between the ocular surface and lacrimal glands. Cornea. 1998 Nov; 17(6):584-89.

9. Zoukhri D. Effect of inflammation on lacrimal gland function. Exp Eye Res. 2006 May;82(5):885-98.

10. Gao J, Morgan G, Tieu D, et al. ICAM-1 expression predisposes ocular tissues to immune-based inflammation in dry eye patients and Sjögrens syndrome-like MRL/lpr mice. Exp Eye Res 2004 Apr;78(4):823-35.

11. Nagelhout TJ, Gamache DA, Roberts L, et al. Preservation of tear film integrity and inhibition of corneal injury by dexamethasone in a rabbit model of lacrimal gland inflammation-induced dry eye. J Ocu Pharmaco Ther. 2005 Apr;21(2):139-48.

12. Luo L, Li DQ, Doshi A, et al. Experimental dry eye stimulates production of inflammatory cytokines and MMP-9 and activates MAPK signaling pathways on the ocular surface. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004 Dec;45(12):4293-301.

13. Niederkorn JY, Stern ME, Pflugfelder SC, et al. Desiccating stress induces T cell-mediated Sjögren’s Syndrome-like lacrimal keratoconjunctivitis. J Immunol. 2006;176(7):3950-7.

14. Farris RL. Tear osmolarity-a new gold standard? Adv Exp Med Biol. 1994;350:495-503.

15. Noecker R. Effects of common ophthalmic preservatives on ocular health. Adv Ther. 2001 Sep-Oct;18(5):205-15.

16. Tripathi BJ, Tripathi RC, Kolli SP. Cytotoxicity of ophthalmic preservatives on human corneal epithelium. Lens Eye Toxic Res. 1992;9(3-4):361-75.

17. Management and therapy of dry eye disease. Ocul Surf. 2007;5(2):163-78. Available at:

www.tearfilm.org/dewsreport (Accessed November 18, 2010).

18. Pflugfelder SC, Maskin SL, Anderson B, et al. A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled, multicenter comparison of loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension, 0.5%, and placebo for treatment of keratoconjunctivitis sicca in patients with delayed tear clearance. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004 Sep;138(3):444-57.

19. Marsh P, Pflugfelder SC. Topical nonpreserved methylprednisolone therapy for keratoconjunctivitis sicca in Sjögren syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1999 Apr;106(4):811-6.

20. Sainz De La Maza M, Serra M, Simón Castellvi C, Kabbani O. Nonpreserved topical steroids and lacrimal punctal occlusion for severe keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2000 Nov;75(11):751-6.

21. Avunduk AM, Avunduk MC, Varnell ED, Kaufman HE. The comparison of efficacies of topical corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drops on dry eye patients: a clinical and immunocytochemical study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003 Oct;136(4):593-602.

22. Yang CQ, Sun W, Gu YS. A clinical study of the efficacy of topical steroids on dry eye. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2006 Aug;7(8):675-8.

23. Foulks GN. Steroids in the treatment of dry eye disease. Eyecare Educators. Available at:

www.eyecareeducators.com/site/steroids_in_the_treatment_of_dry_eye_disease.htm (Accessed November 18, 2010).

24. Donnenfeld E, Sheppard JD, Holland EJ, et al. Prospective, multi-center, randomized controlled study on the effect of loteprednol etabonate on initiating therapy with cyclosporin A. Presented at the AAO Annual Meeting. 2007; New Orleans.

25. Holland EJ, Donnenfeld ED, Lindstrom RL, et al. Expert Consensus in the Treatment of Dry Eye Inflammation. Ophthalmology Times. 2007Apr;32(Suppl):3-11.