|

Managing Contact Lens-associated Red Eye

Treatment of these patients requires a stepwise approach.

By Jennifer Harthan, OD

Release Date: December 15, 2021

Expiration Date: December 15, 2024

Estimated Time to Complete Activity: 2 hours

Jointly provided by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM) and Review Education Group.

Educational Objectives: After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to:

- Identify the signs and symptoms of contact lens-associated red eye.

- Educate patients on contact lens-associated red eye.

- Understand the available therapeutics for this condition.

- Effectively treat contact lens-associated red eye.

- Minimize the risk of recurrence.

Target Audience: This activity is intended for optometrists engaged in managing patients with contact lens-associated red eye.

Accreditation Statement: In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by the Postgraduate Institute for Medicine and Review Education Group. Postgraduate Institute for Medicine is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education, and the American Nurses Credentialing Center, to provide continuing education for the healthcare team. Postgraduate Institute for Medicine is accredited by COPE to provide continuing education to optometrists.

Faculty/Editorial Board: Jennifer Harthan, OD

Credit Statement: This course is COPE approved for 2 hours of CE credit. Activity #122796 and course ID 75266-GO. Check with your local state licensing board to see if this counts toward your CE requirement for relicensure.

Disclosure Statements:

Author: Dr. Harthan has received fees from Allergan, Essilor, Euclid, the International Keratoconus Academy, Kala, Metro Optics and SynergEyes and conducted research with Bausch + Lomb, Kala and Ocular Therapeutix.

Managers and Editorial Staff: The PIM planners and managers have nothing to disclose. The Review Education Group planners, managers and editorial staff have nothing to disclose.

Many ODs have seen patients present with contact lens-associated red eye (CLARE), an inflammatory response to overnight lens wear that involves the cornea and conjunctiva.1 While often easy to treat, it requires ongoing patient education to avoid recurrence.

Our job is to not only identify the signs and symptoms of CLARE but to also ask the right questions, including onset and severity of symptoms, history of extended wear with contact lenses, upper respiratory tract infection, noncompliance with contact lens wear and care and reduction in vision. This can help guide diagnosis and rule out differentials in the contact lens wearer, such as contact lens-induced peripheral ulcer, infiltrative keratitis and microbial keratitis. With the proper diagnosis, an appropriate treatment strategy can then be initiated.

Patients with CLARE often ask, “When can I wear my contact lenses again?” For most, treatment is relatively straightforward and begins with discontinuation of contact lens wear, artificial tears to help mitigate symptoms and lengthy patient education. Other patients may need topical antibiotics, topical corticosteroids or topical or oral NSAIDs. If the patient can resume lens wear, practitioners must feel comfortable proceeding with contact lens prescription recommendations that minimize the risk of recurrence and take into account lens fit, material, modality and/or replacement schedule.

This article discusses how to identify CLARE, relevant history to consider and differentials that must be ruled out. ODs must also understand the available therapeutics that can help alleviate symptoms while the cornea heals, including artificial tears, topical and oral NSAIDs and, if necessary, topical antibiotics. Once the patient is ready to resume lens wear, clinicians must know how to minimize risk of recurrence.

|

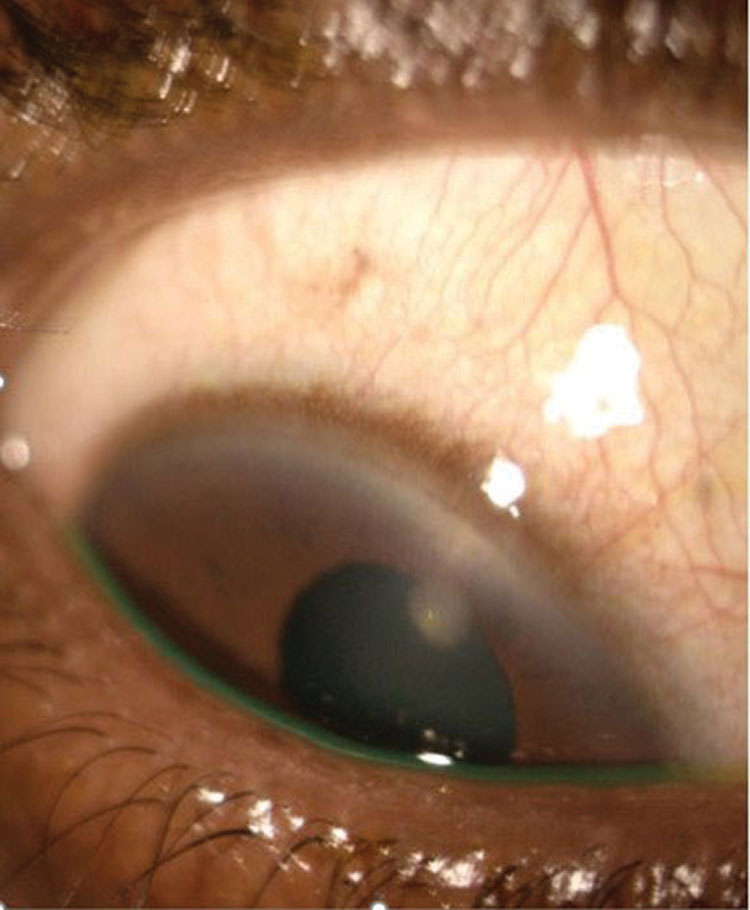

| This patient slept in their contact lenses and woke up with acute redness and pain. They were subsequently diagnosed with CLARE. Note the prominent redness OS. Click image to enlarge. |

The Basics

To better understand CLARE’s etiology, it is important to remember and review the anatomy and functions of the cornea and conjunctiva. The corneal epithelium acts as a protective barrier while the stroma provides strength and transparency, assists in immunity and is the main refracting portion. The endothelium removes fluid from the stroma to maintain clarity, and the basement membranes anchor the epithelium (Bowman’s) and the endothelium (Descemet’s).2,3

The avascular cornea does not have any blood vessels to supply nutrients or protect against infection. It is densely innervated by the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (CN V) via the ciliary nerves.3 The limbus—the zone between the transparent cornea and opaque cornea—houses the stem cells and limbal blood supply to aid in the metabolic demands of epithelial cell renewal and aqueous drainage.3

The conjunctiva—a thin tissue of epithelial and goblet cells—assists with protection and lubrication. It is highly vascularized; the blood supply of the bulbar conjunctiva is primarily via the anterior ciliary arteries, and that of the palpebral conjunctiva is mostly from the branches of the ophthalmic artery.3

Corneal Complications

Look out for these concerns in CLARE patients:

Hypoxia. This occurs when there is a lack of oxygen. Epithelial cells respire anaerobically, lactic acid builds up and the cornea swells. Stromal tissue weakens from chronic edema and stimulates blood vessel growth, causing cells to migrate. Clinical signs include conjunctival redness, limbal redness, epithelial microcysts, endothelial blebs, corneal neovascularization, corneal edema and corneal infiltrates.4

Neovascularization. This is the formation of new blood vessels and extension of vascular capillaries within and into the avascular cornea. This growth is mediated by vascular endothelial growth factor. Initially, the limbal blood vessels dilate, so it’s important to differentiate this occurrence from true neovascularization.

Endothelial cells proliferate and migrate toward the area of insult parallel to the stromal lamellae. Sprouts become tubes with lumen and can mature into small arterioles and venules. If the initiating cause of neovascularization is controlled, the blood vessels may regress and form ghost vessels if chronic.5,6 In contact lens–induced cases, superficial neovascularization is commonly seen.6

Edema. This primarily occurs due to lactate buildup during hypoxia. Fluid builds up in the stroma and over time the endothelial pumps cannot maintain function. Clinically, to differentiate folds from striae, it is important to look at the appearance of “lines” in the posterior stroma. Endothelial folds may appear as long, straight, dark lines in the posterior stroma, whereas striae appear as fine, white, vertical lines in the posterior stroma that do not branch. This occurs with increased hydration in the posterior stroma, which results in collagen fibril separation.7

Infiltrates. These are gray or white aggregates of inflammatory cells. Epithelial cells identify the corneal insult and release cytokines to mount an immune response, and neutrophils and lymphocytes are released from the limbal vessels. The collection of inflammatory cells within the cornea forms an infiltrate and appears whitish-gray in color.8

|

| A patient who presented with an irritated, painful eye after sleeping in her contact lenses was diagnosed with unilateral CLARE. Click image to enlarge. |

What is CLARE?

CLARE is thought to occur in conditions under hypoxic stress and in the presence of gram-negative bacteria that colonize contact lens surfaces, stimulating an inflammatory event of the cornea and conjunctiva, secondary to the release of bacterial endotoxins.8-11

There are several risk factors for CLARE, including extended contact lens wear, tight-fitting lenses, high water lenses, replacement noncompliance, improper contact lens solution use, poor contact lens hygiene and a history of upper respiratory tract infection.9,10,12

Patients with CLARE have an acute onset and wake up with symptoms of irritation to moderate pain, epiphora and photophobia. They often have prominent circumlimbal redness and may present with multiple, small focal or diffuse infiltrates that rarely stain with sodium fluorescein. There may also be associated corneal edema and haze.8-10

Patient Case History

As with other “red eye” conditions, a detailed case history is crucial when making an accurate and timely diagnosis. Asking focused questions can also eliminate many conditions from your list of differentials.

CLARE is associated with sleeping in contact lenses, so detailed questions about a patient’s wear schedule and hygiene habits are important.9,13 This condition has also been linked to extended wear, tight-fitting, low oxygen, high water hydrogel contact lenses, as well as extended wear, high oxygen, silicone hydrogel lenses.8,10,12

Sometimes, asking a patient if they sleep in their contact lenses will automatically elicit a “no” response. The patient may be embarrassed or fearful of not being able to wear lenses in the future. Additional questions such as, “Do you nap in your contact lenses?” or “How many hours per day do you sleep in your lenses?” or “How many days per week do you sleep in your lenses?” may provide a more truthful response.

For new patients, knowing what type of lenses they wear may benefit future management options. Some patients don’t know what lenses they are wearing, so asking about their replacement schedule, solution(s) used and any difficulty with lens removal can provide helpful information.

Additional questions to ask patients, particularly in the case of recurrent episodes, include previous treatment(s) they have received and whether they have a pair of spectacles. Knowing the answers to these questions may help address noncompliance. It is also important to ask patients presenting with symptoms of CLARE about any recent upper respiratory illness, as Haemophilus influenza has been associated with infiltrative events and CLARE.9,12,14

|

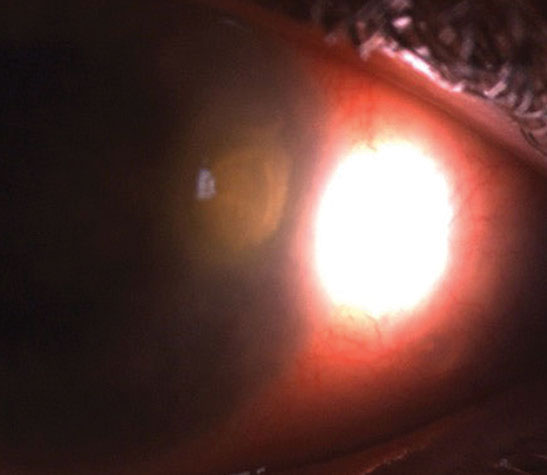

| This patient was diagnosed with a CLPU with minimal corneal staining overlying the infiltrate. Click image to enlarge. |

Signs and Symptoms

Patients with CLARE often present with a sudden onset of mild to moderate pain, photophobia, epiphora, contact lens intolerance and overall discomfort. They may have unilateral or bilateral involvement. Slit lamp exam will reveal mild to moderate conjunctival and limbal hyperemia, along with corneal epithelial and subepithelial infiltrates in the periphery to midperiphery.

Infiltrates with CLARE will have little to no sodium fluorescein staining, as there is minimal associated epithelial disruption.9,13,15 Vision is typically not affected. However, the number of infiltrates varies, and in severe or recurrent cases of CLARE, vision may be affected due to subsequent corneal scarring.9,12 In severe cases of CLARE, corneal edema and/or uveitis may also be present.9,12

Differentials

To initiate appropriate therapy and prevent complications, it’s imperative to differentiate CLARE from conditions such as microbial keratitis, infiltrative keratitis and contact lens peripheral ulcers (CLPUs).

Microbial keratitis. This rare but potentially serious and sight-threatening complication of contact lens wear typically results from bacterial pathogens but can also be caused by amoeba and fungi.9,16 Trauma and epithelial defects predispose the cornea to infection; depending on the pathogen, patients will present with increasing levels of pain, redness, inflammation and photophobia.8,9,16,17

Patients often have decreased vision, particularly if microbial keratitis is within the visual axis; however, the condition is not limited to a specific region. Unlike CLPUs, infiltrative keratitis and CLARE, patients with microbial keratitis will typically have a more significant epithelial defect that stains with sodium fluorescein and overlies a dense white stromal infiltrate. Corneal thinning, stromal edema, Descemet’s folds, an intense anterior chamber reaction and mucopurulent discharge are also associated signs. If untreated, corneal perforation may occur, depending on the causative pathogen.

Infiltrative keratitis. This is an inflammatory reaction that occurs over a period of days vs. CLARE’s acute onset. Symptoms include mild to moderate irritation, redness and occasional discharge. Anterior stromal infiltrates will be present in the midperipheral to peripheral cornea that may or may not stain with fluorescein. Infiltrative keratitis is associated with bioburden on the eyelids from Staphylococcus aureus, contact lenses, contact lens cases and extended contact lens wear.8 Management of infiltrative keratitis includes discontinuation of contact lens wear, lid hygiene, artificial tears, topical steroids or a topical steroid/antibiotic combination. Once the condition has completely resolved, the patient may be refit into a different contact lens modality with decreased wear.8

CLPUs. This is also an inflammatory response and has been called a “sterile ulcer.” Patients may be asymptomatic or have symptoms of moderate to severe irritation or pain. Slit lamp exam will show a small, circular, well-defined focal infiltrate usually <2mm in size in the peripheral cornea at the depth of the anterior stroma with Bowman’s remains intact. With a CLPU, there will be fluorescein staining if an epithelial defect overlys the infiltrate. There may also be an anterior chamber reaction associated with the infiltrate.17

CLPUs are linked with gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus) and extended contact lens wear.8 It is critical to differentiate a CLPU from an infectious etiology before initiating therapy. Treatment is targeted at eradicating the underlying pathogen, decreasing inflammation and healing the tissue.16,17 During treatment, lens wear should be discontinued. Eye care practitioners may prescribe a topical prophylactic or fortified antibiotic, topical steroid or steroid/antibiotic combination. These patients require close observation and daily follow-up. Once the condition has resolved, the patient’s contact lens modality should be changed, usually to one of less frequent wear and with increased oxygen transmissibility.8

|

| This large epithelial defect overlies a dense stromal infiltrate in microbial keratitis. The patient presented with significant pain, mucopurulent discharge and reduced vision. Click image to enlarge. |

Stepwise Management

Once it has been determined that a patient has CLARE, a stepwise plan can—and should—be initiated.

Discontinue contact lens wear. Management begins with this step to remove the trigger for inflammation. Patients must be educated to not wear their lenses until their signs and symptoms have completely resolved. This may take several weeks depending on the number and severity of the infiltrates. Some may resist, particularly if they do not have a backup pair of spectacles or have high refractive error. Educating the patient on the etiology, possibility of recurrence and importance of treatment compliance and follow-up is important, especially if resuming contact lens wear is the goal.

Supportive care. Many patients may not need further management beyond discontinuation of contact lenses and supportive care with artificial tears, as the inflammatory condition is typically self-limited.8,10

Therapeutics. The amount of corneal staining overlying the infiltrates and the level of patient discomfort can help determine if—and when—therapeutics are needed. Instillation of sodium fluorescein is beneficial to determine the size of the epithelial defect over each infiltrate. For patients who have increased corneal staining, a differential of microbial keratitis needs to be ruled out. If corneal staining is present, a broad-spectrum topical antibiotic should be deployed for 24 to 48 hours to minimize risk of infection. Some practitioners prefer a steroid/antibiotic combination to concurrently treat the inflammatory reaction.

Initially, patients are followed every 24 hours until corneal staining completely resolves, then a topical steroid or antibiotic/steroid combination can be prescribed to help decrease inflammation. These are often prescribed four times daily and tapered as the inflammatory reaction shows signs of improvement.8,10

More symptomatic patients can be prescribed a topical cycloplegic and/or a topical or oral NSAID to improve comfort. If an anterior chamber reaction is present along with the infiltrates, a topical steroid may be considered to decrease inflammation and improve comfort.

Return to contact lens wear. Once the inflammatory reaction has completely resolved, it may be determined that a patient can resume lens wear. It’s critical to educate the patient that under no circumstance should they wear lenses on an extended wear basis, and if they do so, it will increase the risk of recurrence. There are several options to manage the contact lens patient as they return to wear, and it is important to remember that there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach that will work for every patient.

Refitting a patient from extended wear to daily wear is usually the first step and, if possible, a daily disposable should be the modality of choice. If this may not be possible, increasing the frequency of lens replacement, reducing wear time throughout the day, increasing oxygen transmissibility and changing the to a hydrogen peroxide-based system are all beneficial options.

It is also important to evaluate the lens fit and make sure that there is acceptable movement, particularly if the previous fit was too tight or unacceptable. For many patients, changing the lens fit, modality, material and/or replacement schedule will help prevent recurrence of CLARE. For others, it may not, as some patients continue to sleep in their contact lenses and have recurrent episodes. For noncompliant patients, complete cessation of lens wear may need to take place.8,17

CLARE is not a difficult condition to manage, but it can take time to educate patients on the importance of compliance with lens wear cessasion to minimize risk of recurrence. A detailed case history and careful examination to measure the size of the epithelial defect over the underlying infiltrate to rule out infiltrative keratitis, CLPUs and microbial keratitis are important in determining the appropriate management. With a clear understanding of the condition and the potential differentials, optometrists can effectively manage these patients.

Dr. Harthan is a graduate of the Illinois College of Optometry (ICO), where she completed a residency in cornea and contact lenses. She is a professor at ICO and chief of the Cornea Center for Clinical Excellence at the Illinois Eye Institute.

1. Stapleton F, Ramachandran L, Sweeney D, et al. Altered conjunctival response after contact-lens related corneal inflammation. Cornea. 2003;22(5)443-7. 2. Eghrari A, Riazuddin A, Gottsch J. Overview of the cornea: structure, function, and development. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2015;134:7-23. 3. Downie L, Bandlitz S, Bergmansonm J, et al. CLEAR—anatomy and physiology of the anterior eye. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2021;44(2):132-56. 4. Safvati A, Cole N, Hume E, et al. Mediators of neovascularization and the hypoxic cornea. Curr Eye Res. 2009;34(6)501-14. 5. Labelle P. The eye. Pathol Basis Vet Disease. 2017:1265-318. 6. Efron N. Corneal neovascularization. In: Contact Lens Practice (third edition). Elsevier; 2018. 7. Efron N. Contact lens wear is intrinsically inflammatory. Clin Exp Optom. 2017;100(1):3-19. 8. Robboy M, Comstock T, Kalsow C. Contact lens-associated corneal infiltrates. Eye Contact Lens. 2003;29(3):146-54. 9. Stapleton F, Keay L, Jalbert I, et al. The epidemiology of contact lens related infiltrates. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84(4):257-72. 10. Sicks LA. Bringing clarity to CLARE. RCCL. 2015;152(4):16-9. 11. Holden BA, La Hood D, Grant T, et al. Gram-negative bacteria can induce contact lens acute red eye (CLARE) responses. CLAO J. 1996;22(1):47-52. 12. Dumbleton K, Jones L. Extended and continuous wear. In: Clinical Manual of Contact Lenses. Bennett E, Henry V, eds. Williams and Wilkins; 2008:410-43. 13. Sweeney DF, Jalbert I, Covey M, et al. Clinical characterization of corneal infiltrative events observed with soft contact lens wear. Cornea. 2003;22(5):435-42. 14. Sankaridurg PR, Willcox MD, Sharma S, et al. Haemophilus influenzae adherent to contact lenses associated with production of acute ocular inflammation. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34(10):2426-31. 15. Shovlin JP. Clear cause of CLARE. Rev Optom. 2004;141(9):127. 16. Lakhundi S, Siddiqui R, Khan N. Pathogenesis of microbial keratitis. Microb Pathog. 2017;104:97-109. 17. Alipour F, Khaheshi S, Soleimanzadeh M, et al. Contact lens-related complications: a review. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2017;12(2):193-204. |