A Deeper Look at DEWS II Making the Diagnosis with TFOS DEWS II |

A notable addition to TFOS DEWS II is a report on iatrogenic dry eye. Not a subject covered in the original DEWS report, it was time to acknowledge “the number of cases of dry eye that are caused by medical examination or treatment such as topical medications, systemic drugs, ophthalmic surgical procedures and even cosmetic procedures,” says James S. Wolffsohn, PhD, a member of the DEWS II iatrogenic subcommittee and harmonizer for the report.

The goals of the subcommittee included the development of a classification system to help identify iatrogenic causes of dry eye as well as prophylaxis and management recommendations. To get there, they first had to define iatrogenic dry eye, which led to a consensus of “dry eye induced unintentionally by medical treatment from a physician or a health-related professional,” Subcommittee Chair José Alvaro Gomes, MD, said during the 2017 ARVO session in which the report was introduced.

The subsequent classification system covered the following categories: ophthalmic surgery, pharmaceuticals, contact lenses (CLs), non-surgical ophthalmic procedures and non-ophthalmic conditions.1

This article discusses the new findings in iatrogenic dry eye and how you can use them to better serve your patients.

|

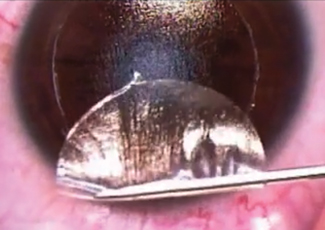

| During LASIK flap creation, corneal nerves are severed, which can induce dry eye. Photo: Derek N. Cunningham, OD, and Walter O. Whitley, OD, MBA |

Procedures

Findings in surgery-induced dry eye are among the most revealing of the report. The subcommittee looked closely at the literature on refractive, cataract, lid, conjunctival, glaucoma, vitreoretinal and strabismus surgeries, as well as keratoprosthesis, intrastromal corneal ring segment implantation.

Refractive Surgery. The research on dry eye symptoms after laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) reveals a wide range of incidence statistics based on factors such as the severity cut-off and whether the patient had pre-existing dry eye disease (DED).2-11 Some studies suggest that photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) induces fewer dry eye symptoms than LASIK because it only damages corneal nerve endings, resulting in faster regeneration.12,13 The subcommittee is quick to point out, however, that it is unclear “whether there is retrograde degeneration of nerves following terminal injury in the cornea.”1

Prior to surgery, the most common cause of dry eye is obstructive meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD).14-16 After the procedure, dry eye causes include the effects of neurotrophic influences on the lacrimal functional unit.17

To best manage dry eye in refractive surgery patients, the subcommittee recommends treating pre-existing DED, ocular rosacea or blepharitis before surgery. Restasis (cyclosporin A, Allergan) is an effective treatment in some cases, but adjuvant options include nonpreserved artificial tears and ointments, dietary alpha omega fatty acids, maintaining more than 40% to 50% humidity, punctal plugs and even autologous serum drops.18 In general, clinicians should continue the selected course of treatment for six to eight months after surgery.19

Cataract Surgery. Although the majority of these patients are older (between 43 to 84 years of age according to one study) and more likely to have pre-existing DED, the surgery itself may temporarily induce or exacerbate dry eye on its own.20-25 Of note, diabetes patients show an increased vulnerability to dry eye after undergoing cataract surgery.26,27 Potential contributors to cataract surgery-induced dry eye include topical anesthetics and desiccation, nerve transection, elevation of inflammatory factors, goblet cell loss and MGD.28

As with refractive surgery, management of these cases begins with identifying and treating ocular rosacea, blepharitis and ocular surface disease prior to surgery.29-31 Here, however, clinicians should avoid lid hygiene treatments shortly before or after surgery to avoid any infectious complications.1 “Care should be taken to avoid lid hygiene immediately prior to, or shortly after, the surgery, as the eyelids harbor pathogens that could be introduced to the ocular surface, increasing the risk of infections such as endophthalmitis when the cornea is compromised through an incision to implant an intraocular lens,” says Dr. Wolffsohn.

The subcommittee recommends using medical therapy or artificial tears that include hyaluronate or carboxymethylcellulose to improve dry eye signs and symptoms after cataract surgery.32-36

|

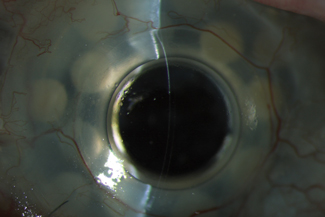

| Studies have shown that reorganization of the nerves after keratoprosthesis implant is a possible cause of DED. Photo: James Aquavella, MD |

Lid Surgery. A close interaction of the eyelid, tear film and ocular surface could be a possible cause of dry eye in lid surgery patients.37 These surgeries often cause DED onset or exacerbate preoperative disease, which, according to the report, is common but overlooked.37-41 Management options include artificial tears and lubrication throughout the night (specifically, unpreserved products), topical steroids and Restasis.40,41 In persistent cases, surgical intervention such as tape tarsorrhaphy and lower lid repositioning may be necessary. Here, the subcommittee recommends addressing ocular surface issues prior to surgery.

Other Surgeries. In keratoprosthesis implantation, post-procedure nerve reorganization surfaced as a possible culprit for dry eye. “It has been shown, for example, that following penetrating keratoplasty, central corneal sensitivity decreased and then returned to near normal levels after 12 months, but no sub-basal nerves were detected,” says Dr. Wolffsohn. “Hence regeneration may not follow the initial structure, which has a negative effect on ocular surface simulation of the tear film components.”

For conjunctival surgery, the subcommittee found a relationship between pterygium growths and DED, although it is still not entirely clear if the growths actually cause the disease.42 Some other surgeries that showed links to dry eye without concrete causation include glaucoma surgery, vitreoretinal surgery, strabismus surgery and intrastromal corneal ring surgery.1

Drug-induced Dry Eye

This can be related to either topical or systemic medications:1

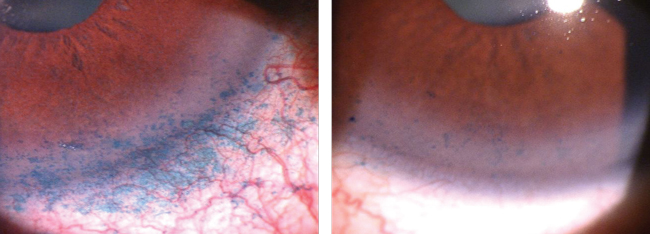

Topicals. The subcommittee found that the concentration of preservatives in glaucoma medications, specifically benzalkonium chloride (BAK), has the potential to cause inflammation and proptosis. “Due to financial prudence, health services tend to initially prescribe preserved glaucoma medications, as they are generally less expensive,” says Dr. Wolffsohn. “Preservatives damage the ocular surface and can exacerbate dry eye.”

Additionally, investigators say a number of other topical drugs can “cause or aggravate” DED, but because they are commonly tested in preserved formulations, the respective roles of the drug, preservatives and excipients isn’t exactly clear).1

|

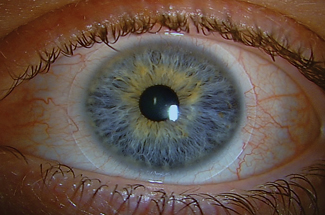

| A hypersensitivity or toxic reaction to the preservative in a contact lens solution can cause dry eye symptoms and is typically characterized by conjunctival injection and superficial punctate keratitis. Photo: Heidi Wagner, OD, MPH |

To manage cases where topical drugs are the suspected dry eye culprit, ODs should discontinue the drug, if possible.1 This becomes tricky if several drugs are being used at once or if discontinuation of the drug would endanger the patient’s eye health. Eye drops can alleviate dry eye symptoms, and in severe cases, laser trabeculoplasty or surgery may be necessary. Alternatively, ODs could use low toxicity preservatives such as brimonidine to minimize the drug’s toxicity.43

Systemics. Of the top 100 best-selling systemic drugs in the United States in 2009, 22 can possibly cause dry eye symptoms.44 The DEWS II iatrogenic subcommittee compiled a lengthy list of systemic drugs with either a “known or suspected link to dry eye symptoms.” These range from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to multivitamins, and their associations with dry eye symptoms vary.1

To identify a problematic systemic drug in these cases, practitioners can often withdraw and then reintroduce the drug in question.1 For cases in which discontinuation is not possible, options include adjusting the dosage to a point where the drug is still effective but with reduced dry eye symptoms, switching to a medication of a different mechanism or, in mild cases, adding lubricants or similar topical treatments.

CL-induced Dry Eye

Factors involved in dry eye stemming from CL wear include biophysical changes to the tear film such as a thinner lipid layer and increased tear evaporation, and ocular responses such as alterations to Langerhans cells, conjunctival goblet cell density and lid wiper epitheliopathy. Of course, existing DED can be exacerbated by lens wear, and lenses can induce a dry eye state.1

The report also found evidence that CLs affect meibomian gland expressibility, the number of plugged and expressible orifices and gland-related dropout. “In vivo confocal microscopy of the meibomian glands shows significantly decreased basal epithelial cell density, lower acinar unity diameters, higher glandular orifices diameters and greater secretion reflectivity with contact lens wear,” says Dr. Wolffsohn. “There is no evidence that these changes are reversible, so clinicians should make sure that contact lenses have minimal impact on the ocular surface to hopefully minimize changes to the meibomian glands.”

When a patient has CL-induced dry eye, management options include switching to daily disposable lenses, introducing lenses with internal wetting agents, using topical wetting agents, hydroxypropyl cellulose ophthalmic inserts, hydrogen peroxide disinfection, omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid supplementation, punctual plugs, azithromycin, reduced lens wear time and, if needed, discontinuation of lens wear.1

|

| Lissamine green staining of the conjunctiva and cornea identifies BAK toxicity from chronic prostaglandin use. This patient was switched to a preservative-free prostaglandin analog. His signs and symptoms of dry eye improved over the next three months. Photo: James Aquavella, MD |

Nonsurgical Ophthalmic Procedures

Botox (botulinum toxin, Allergan), a neurotoxin used to treat various conditions such as blepharospasm, migraine and cervical dystonia, has emerged as a possible cause of DED.1,45 Patients with dry eye symptoms after Botox treatment may experience relief with artificial tears; if symptoms persist after 12 months, surgical intervention such as lateral musculoplasty may be required.

Other nonsurgical ophthalmic procedures that show a lesser degree of dry eye prevalence include corneal collagen crosslinking, positive pressure noninvasive ventilation, radiation treatment, eye makeup, tattooing and piercing.1

The past 10 years of research shows that the inclusion of iatrogenic dry eye in DEWS II was necessary, and the results will help practitioners better handle ambiguous DED. The report “drills down into the specifics of each treatment or condition of a patient,” says Dr. Wolffsohn, “so it really provides clinicians with a useful guide to some of the key areas they need to concentrate on in patient history and symptoms.”

1. Gomes JAP, Azar DT, Baudouin C, et al. TFOS DEWS II iatrogenic report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):511-38. |