When fitting contact lenses, the status of the ocular surface is our primary focus. The cornea, conjunctiva and sclera support the lens and are the major contributors to the fit. But, by focusing solely on these structures, we often fail to acknowledge the equally important role the eyelids play. The interaction between the eyelids and a contact lens can significantly contribute to contact lens success. This article reviews complications that may arise from surgical alterations to the lids, including lid closure and lesion removal, and investigates how anatomical variations, such as lid tension, can influence the lens fit.

|

| Fig. 1. Note the narrowing of palpebral fissure vertically and horizontally in this partial temporary tarsorrhaphy. Photo: Pratik Patel, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Eyes Wide Shut

One of the most difficult eyelid issues to overcome when fitting contact lenses is a partial tarsorrhaphy, or surgical closure of the eyelids, which is primarily indicated to prevent exposure of the ocular surface. The etiology of the exposure may include non-resolving Bell’s palsy, acoustic neuroma causing seventh cranial nerve paresis, exophthalmos or neurotrophic disease.1

The surgical technique depends on how long the lids should be closed. For temporary tarsorrhaphies, the lids can be partially or completely closed. Non-absorbable sutures create “drawstrings” that can be tightened or loosened to control the size of the interpalpebral fissure.

Fully opening the lids is crucial for examining the entire ocular surface at follow-up and ensuring proper healing. As ocular surface healing takes place, the degree of lid closure can be optimized for visual quality, patient comfort and ocular health. The ability to control fissure size makes this technique more popular than permanent closure.

In the case of permanent closure, usually only the lateral-most portion of the lids is approximated. During surgery, the surgeon separates the anterior lamella (skin side of the lids) from the posterior lamella (conjunctival side) with a #11 or #15 blade. Next, they remove the epithelium from the lid margin. Separating the anterior and posterior portions of the lid and removing the lid margin tissue allow the upper and lower portions of the anterior and posterior lamella to heal. The posterior lamella of the upper and lower lid is then connected using absorbable sutures, and the anterior lamella of the upper and lower lid is connected using non-absorbable sutures. Patients are still able to see, but the interpalpebral fissure is narrower vertically and horizontally to protect a portion of the ocular surface from exposure (Figure 1).1

Drawbacks of tarsorrhaphy include poor functionality and aesthetics. In addition, the procedure may not provide adequate corneal coverage or allow segmental deterioration over time. Examination of the cornea is usually difficult, and the patient’s vision and visual field are restricted.2

Despite partial surgical closure of the lids, some patients may still need protection from ocular surface exposure. In these cases, a bandage soft contact lens is often indicated. While a scleral lens may be an effective treatment option, the large diameter of the lens makes placement on the eye difficult. In most cases, it is easiest to start with standard-sized bandage soft lenses, which range from 13.8mm to 14.0mm in diameter. Standard lenses may prove to be too large but are often readily available in most clinical settings.

Trial and error informs the provider on what adjustments are necessary or if a custom lens is required. Diameters of custom soft lenses usually range anywhere from 11.0mm to 22.0mm to fit the various needs of patients. Regardless of base curve and diameter, the lens may need to be partially folded to “tuck” one edge under the upper lid and then position the inferior edge under the lower lid. Patients who are unable to place the lens themselves should return every three to four weeks for lens replacement.

|

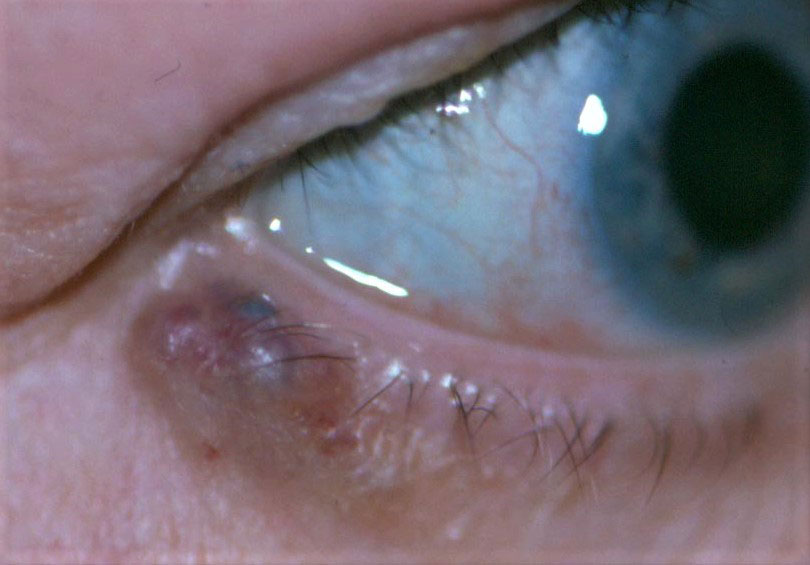

| Fig. 2. A pigmented basal cell carcinoma margin lesion is noticeable on this eyelid. Click image to enlarge. |

A Bumpy Road

As eyecare providers, we are no strangers to lid lesions. Patients with lesions often present with concerns about their aesthetics and to determine if they pose any health risk. Fortunately, approximately 80% of lesions are benign and do not require excision.3 However, even if a lesion is benign and possesses no threat of malignancy, its location may eventually damage the ocular surface and potentially complicate contact lens wear.

A lesion or tumor can form in any of the four layers of the eyelid (skin and subcutaneous tissue, striated muscle, tarsus or conjunctiva), but nearly all lesions are cutaneous in origin and can be categorized as epithelial or melanocytic.

Lesions primarily affect the outermost layer of the lid, meaning they interact with the ocular surface if located along the upper or lower lid margins. The irregular mass disrupts normal function, and the lid no longer acts as a “squeegee” to move tears on the ocular surface. Poor distribution of the tear film and damage to the corneal epithelium can occur and may eventually lead to surface scarring and reduced vision.

While contact lens wear can help protect the ocular surface, it may cause other problems. If the lesion is made up of keratinized epithelial cells (not smooth palpebral tissue), it may snag on the lens. Although it seems contradictory, sometimes this can be beneficial (e.g., an upper lid lesion may help keep a gas permeable lens attached). More often, the lesion causes the lens to move erratically and pop out. As the patient blinks, the margins of the lesion slide under the lens edge and the lens falls out (Figure 2). We have seen this happen with every single modality of lens, including sclerals. The simplest solution, from a lens fitting standpoint, is to increase the lens diameter to prevent the lid margin from crossing over the upper or lower edge of the lens.

However, it is often more effective to address the problem at its source—the lesion. If the lesion is removed, the regularity of the lid margin can be restored.

Whether a lesion is benign or malignant is crucial to determining how it is removed. For lid margin lesions, a shave excision is often preferred to prevent lid margin notching that can occur with other excision techniques.4,5

To perform a shave excision, an anesthetic is injected under the lesion. The skin is then stabilized or stretched using the non-dominant hand, and, using the dominant hand, the lesion is separated from the underlying tissue with a #11 blade, curette or fine wire electrosurgical loop. This is done horizontally with the eyelid margin serving as a guide. The technique maintains the integrity of the underlying tissue and prevents excessive scarring. After removal, the tissue should be sent to pathology to confirm whether it is benign or malignant. The patient should use antibiotic ointment following the procedure to prevent infection.

For known malignant lesions, excision that allows for an additional 3.0mm to 4.0mm margin ensures that all of the malignant tissue is removed. Part or all of the lid margin may need to be removed in some cases. Bandage contact lenses—either soft or scleral—can be applied after the procedure to protect the ocular surface. While smaller custom bandage lenses are needed to accommodate the narrower lid fissure created by a tarsorrhaphy, larger lenses (>16.0mm) are required in the case of a lid lesion to protect the more peripheral conjunctival tissue. When a significant amount of the eyelid is removed, tissue grafts can help restore lid integrity over time. Until then, regular monitoring of ocular surface health is essential.

|

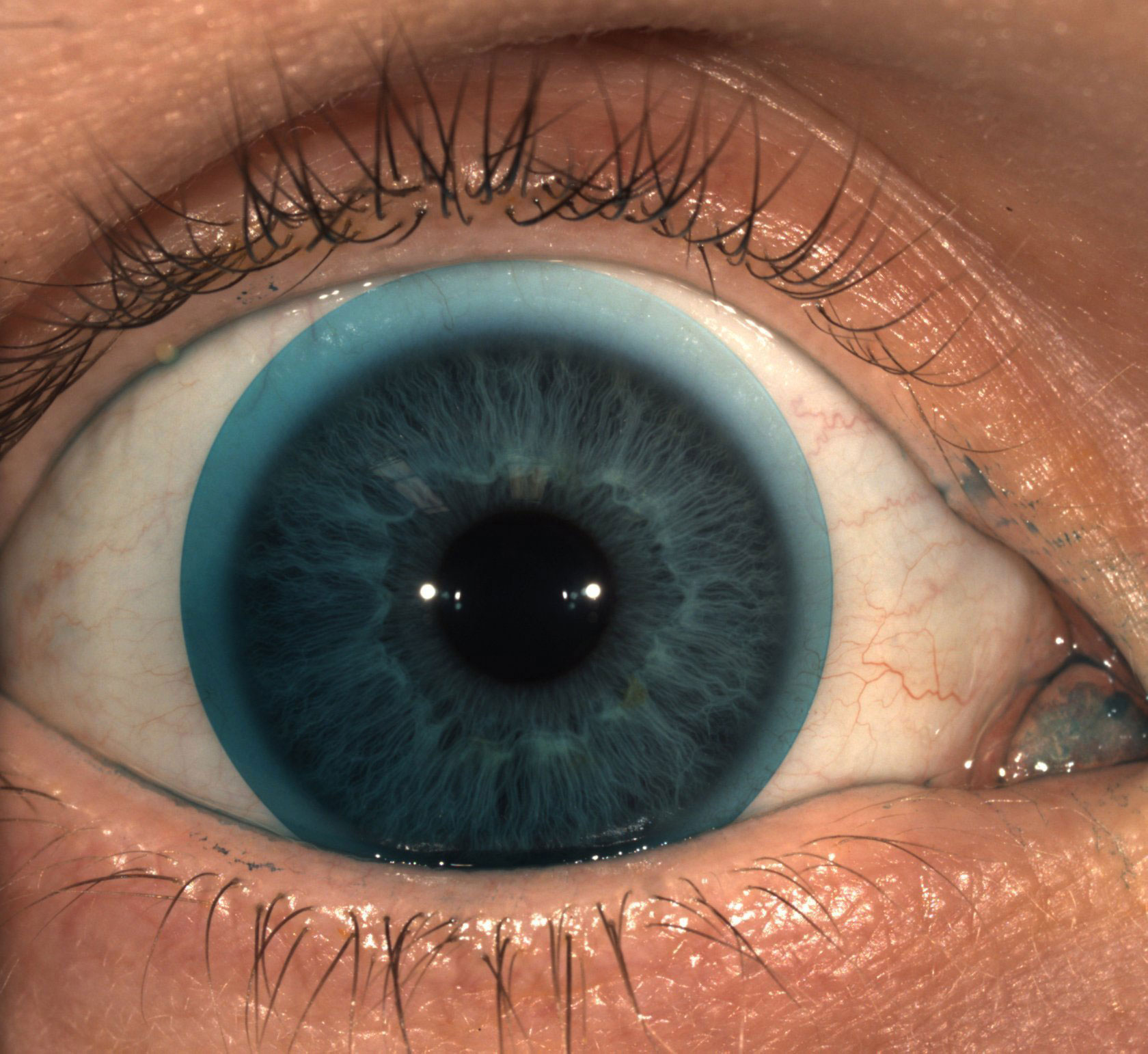

| Fig. 3. Note superior lens decentration when the upper lid is manually elevated and the lower lid is in normal position. Click image to enlarge. |

Down and Out

It is well known that soft contact lenses tend to decenter down and out. We often attribute lens decentration to the height differences of the sclera. Usually, the nasal sclera is higher than the temporal sclera. This difference may occur as a result of the medial rectus being inserted closer to the limbus than the lateral rectus. Similarly, the inferior sclera tends to be lower than the superior sclera. While scleral height most certainly plays a significant role in lens decentration, it could be that the lids—specifically the upper lid—contribute as well.

Researchers have not reached a consensus on the role of superior lid tension in soft contact lens wear. There are a number of competing theories suggesting it plays very different roles in the fitting process. One theory proposes that the closer the upper lid is to the globe, the greater the resistance the lens encounters when trying to move superiorly.6 As a result, those with greater superior lid tension have more inferior lens decentration. The theory also suggests that, on average, younger patients have more inferior soft lens decentration. Recent evidence seems to support this, as the phenomenon that superior lid tension decreases with age is well documented.7 One study revealed that various soft lens designs tended to decenter more in the pre-presbyopic population.8 Another found that soft lenses tended to decenter superiorly when the upper eyelid was held up, which the researchers noted could be explained by the lower lid pushing the lens up, but it did not mention the decrease in resistance from the upper lid when it was held as a possible explanation.9 To our knowledge, no studies specifically compare upper lid tension and soft contact lens decentration (Figure 3).

Regardless of the exact mechanism causing soft lenses to decenter, the result is the same. The optical center of the contact lens settles inferiorly and temporally to our line of sight. For patients who wear soft spherical lenses or even most toric lenses, this mismatch between optical center and line of sight is inconsequential. The optic zone of the lens is large enough to provide a high quality image.

However, for those who wear multifocal contact lenses for myopia or presbyopia, decentration can have a big impact on visual quality. Many believe this is a primary factor in the relatively high failure rate of soft multifocal contact lenses. Fortunately, more custom soft lens manufacturers are offering decentered optic options for their lens designs. Most recommend ordering a lens in the power, base curve and diameter you desire, fitting the lens to measure the amount of lens decentration and then re-ordering the decentered optic lens. Keep in mind that, if lid tension does play a role, the amount of decentration will change over time as a patient’s lid laxity increases with age and will have to be managed accordingly.

The role the eyelids play in contact lens management is often ignored or overlooked. However, in certain circumstances, the lids can have a major impact not only when fitting gas permeable lenses but also when fitting soft or scleral lenses. Whether the lids are too narrow, wide, loose, tight or bumpy, having a few tricks up your sleeve that you can turn to will help improve your success rate. Additionally, don’t be afraid to make a referral for surgery if restoration of normal lid structure makes the fitting process easier. Generally, the less the lids and lens interact, the better.

Dr. Turpin is an optometrist at North Cascade Eye Associates in northwest Washington. He is building a specialty contact lens clinic within the larger practice. He is the founder of Practically Abstract, a website and newsletter dedicated to reviewing contact lens and dry eye research.

Dr. Skorin is a consultant in the Department of Surgery, Community Division of Ophthalmology at the Mayo Clinic Health System in Albert Lea, MN.

| 1. Rajak S, Rajak J, Selva D. Performing a tarsorrhaphy. Community Eye Health 2015;28(89):10-1. 2. Seiff SR, Choo PH, Carter SR. Facial nerve paralysis. In: Mauriello JA, eds. Unfavorable Results of Eyelid and Lacrimal Surgery: Prevention and Management. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann; 2000: 227-41. 3. Yu SS, Zhao Y, Zhao H, et al. A retrospective study of 2228 cases with eyelid tumors. Int J Ophthalmol. 2018;11(11):1835-41. 4. Sundar G, Manjandavida FP. Excision of eyelid tumors: principles and techniques. In: Chaugule SS, Honavar SG, Finger PT, eds. Surgical Ophthalmic Oncology: A Collaborative Open Access Reference. Vol Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019: 15-32. 5. Skorin L, Goemann L. Lumps and bumps be gone. Rev Optom. 2018;155(2):104-5. 6. Cui L, Li M, Shen M, et al. Characterization of soft contact lens fitting using ultra-long scan depth optical coherence tomography. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:5763172. 7. Yamaguchi M, Shiraishi A. Relationship between eyelid pressure and ocular surface disorders in patients with healthy and dry eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(14):DES56-63. 8. Fedtke C, Ehrmann K, Thomas V, et al. Association between multifocal soft contact lens decentration and visual performance. Clin Optom (Auckl). 2016;8:57-69. 9. El-Nimri NW, Walline JJ. Centration and decentration of contact lenses during peripheral gaze. Optom Vis Sci. 2017;94(11):1029-35. |