Herpes Simplex Keratitis: Managing the Masquerader

This review can help you better identify, diagnose and treat this condition.

By Shannon Leon, OD

|

Release Date: November 15, 2020

Expiration Date: November 15, 2023

Estimated time to complete activity: 2 hours

Jointly provided by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM) and Review Education Group.

Educational Objectives: After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to:

- Provide a timely diagnosis and initiate the right therapy for patients with herpes simplex keratitis.

- Review the examination and testing steps for herpes simplex keratitis.

- Recognize what signs and symptoms can reveal herpes simplex keratitis as the cause.

- Treat herpes simplex keratitis properly.

- Discuss the long-term prognosis and how clinicians can monitor for recurrence.

Target Audience: This activity is intended for optometrists engaged in the care of patients with herpes simplex keratitis.

Accreditation Statement: In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by the Postgraduate Institute for Medicine and Review Education Group. Postgraduate Institute for Medicine is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education, and the American Nurses Credentialing Center, to provide continuing education for the healthcare team. Postgraduate Institute for Medicine is accredited by COPE to provide continuing education to optometrists.

Faculty/Editorial Board: Shannon Leon, OD, the South Texas Eye Institute.

Credit Statement: This course is COPE approved for 2 hours of CE credit. Course ID is 70083-SD. Check with your local state licensing board to see if this counts toward your CE requirement for relicensure.

Disclosure Statements:

Dr. Leon has nothing to disclose.

Managers and Editorial Staff: The PIM planners and managers have nothing to disclose. The Review Education Group planners, managers and editorial staff have nothing to disclose.

Herpes simplex viral keratitis (HSVK) is a condition that can frustrate both clinicians and patients alike. It has often been recognized as a ‘clinical masquerader’ due to its occasionally mystifying and varying presentation. These variations can result in delayed diagnosis, which impacts the patient’s time and comfort as well as their overall visual outcomes. Eye care professionals must be able to recognize and treat HSVK efficiently to not only shorten the course of the disease but also reduce permanent corneal scarring and poor visual prognosis.

|

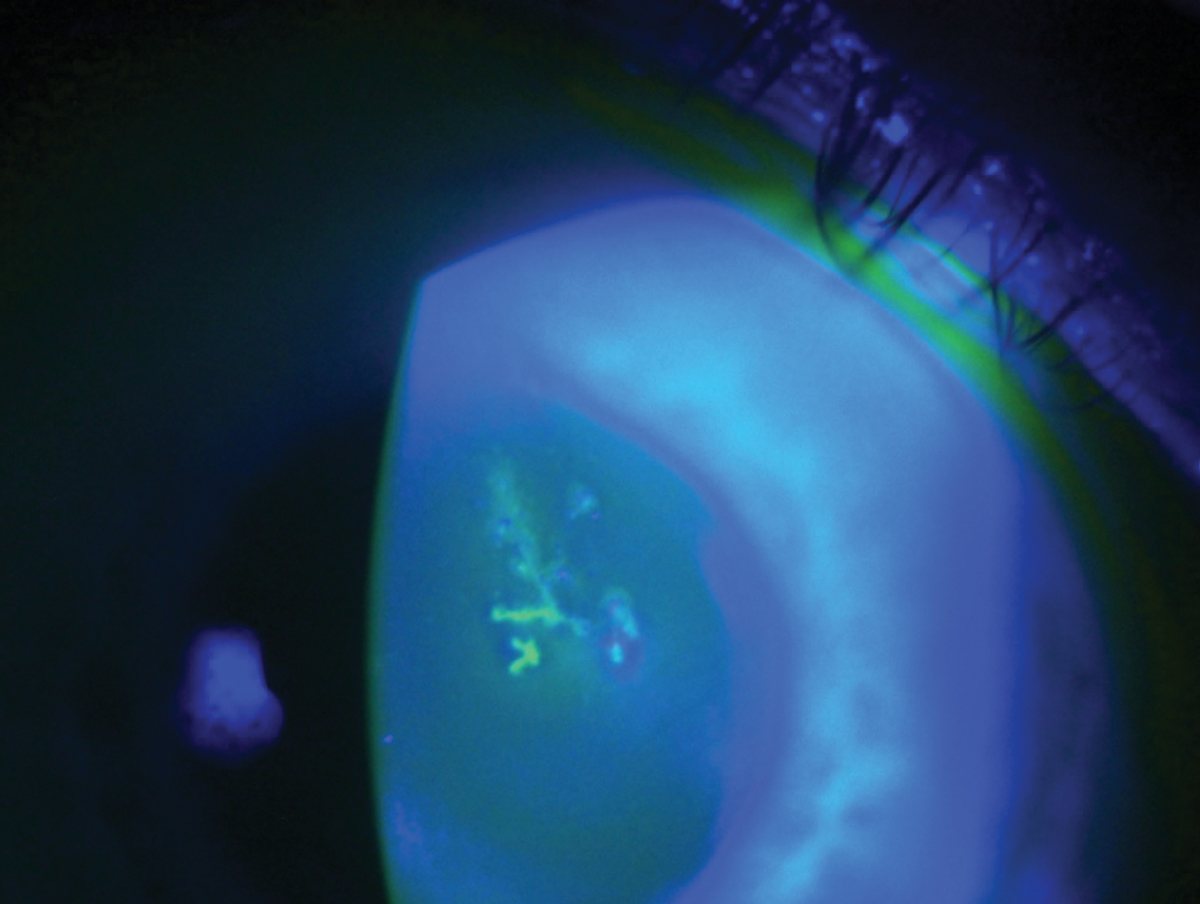

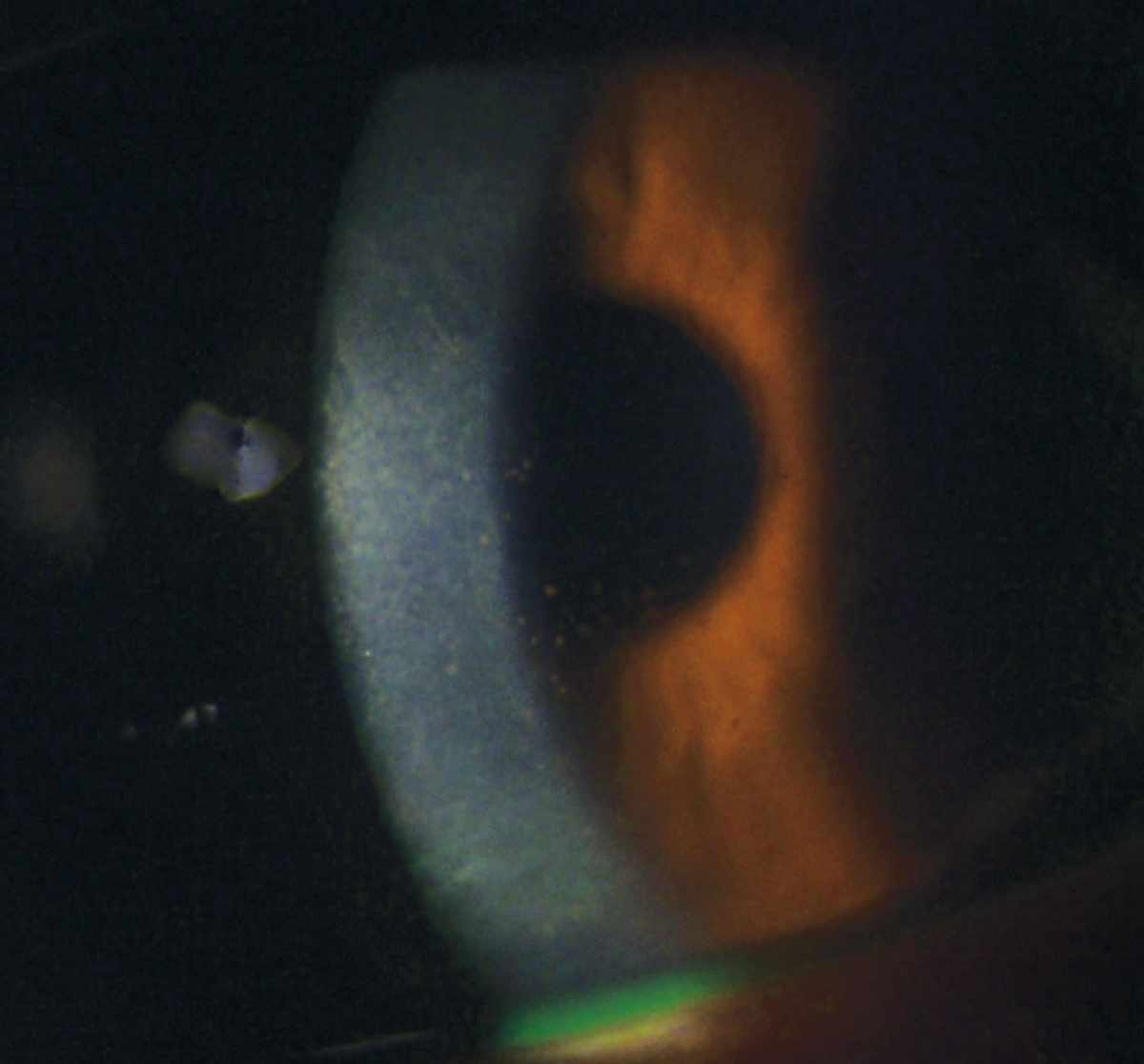

| HSV epithelial keratitis is characterized by a dendrite lesion with terminal bulbs. Photo by Lisa Marten, MD. Click to enlarge. |

HSV Pathology

The herpes simplex virus is a double-stranded DNA virus that spreads via direct contact with the mucous membranes of the host.1,2 It is part of the Herpesviridae family, which includes three main players: herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) and herpes varicella zoster virus (HZV).1 Additional members include the Epstein Barr virus and cytomegalovirus. The challenge of managing HSV ocular infections has risen to prominence not only because of its often-devastating corneal effects but also because of the significant seroprevalence of these viruses within the population. As a result, HSV infections of the eye are the leading cause of infectious corneal blindness in developed countries.2

HSV-1, specifically, is heavily associated with ocular infections and can be difficult to manage due to its reoccurring nature. After initial infection, HSV can move to corneal epithelial cells where it will often continue to replicate and spread from cell to cell.3 This replication results in what we often recognize as the hallmark dendritic corneal lesion.3 The virus then progresses to either cause an immune-mediated inflammatory response, which clinicians call stromal keratitis, or the virus will travel in a retrograde manner along the trigeminal ganglion via the corneal nerves to wait for future reactivation.1,3

A Detailed History

Unfortunately, HSVK can have many clinical presentations and, therefore, should always be on your list of differentials when diagnosing and treating anterior segment disease. When diagnosing a corneal condition, the best place to start is with a thorough history. The majority of HSVK is secondary to viral recurrence, which is often associated with stress, ultraviolet light exposure, corneal trauma or immunosuppression.1Therefore, one of the most important questions you can ask your patient is whether they have had a similar episode in the past. Still, many episodes of HSV are asymptomatic, and the lack of a clear previous history doesn’t rule out the condition.

|

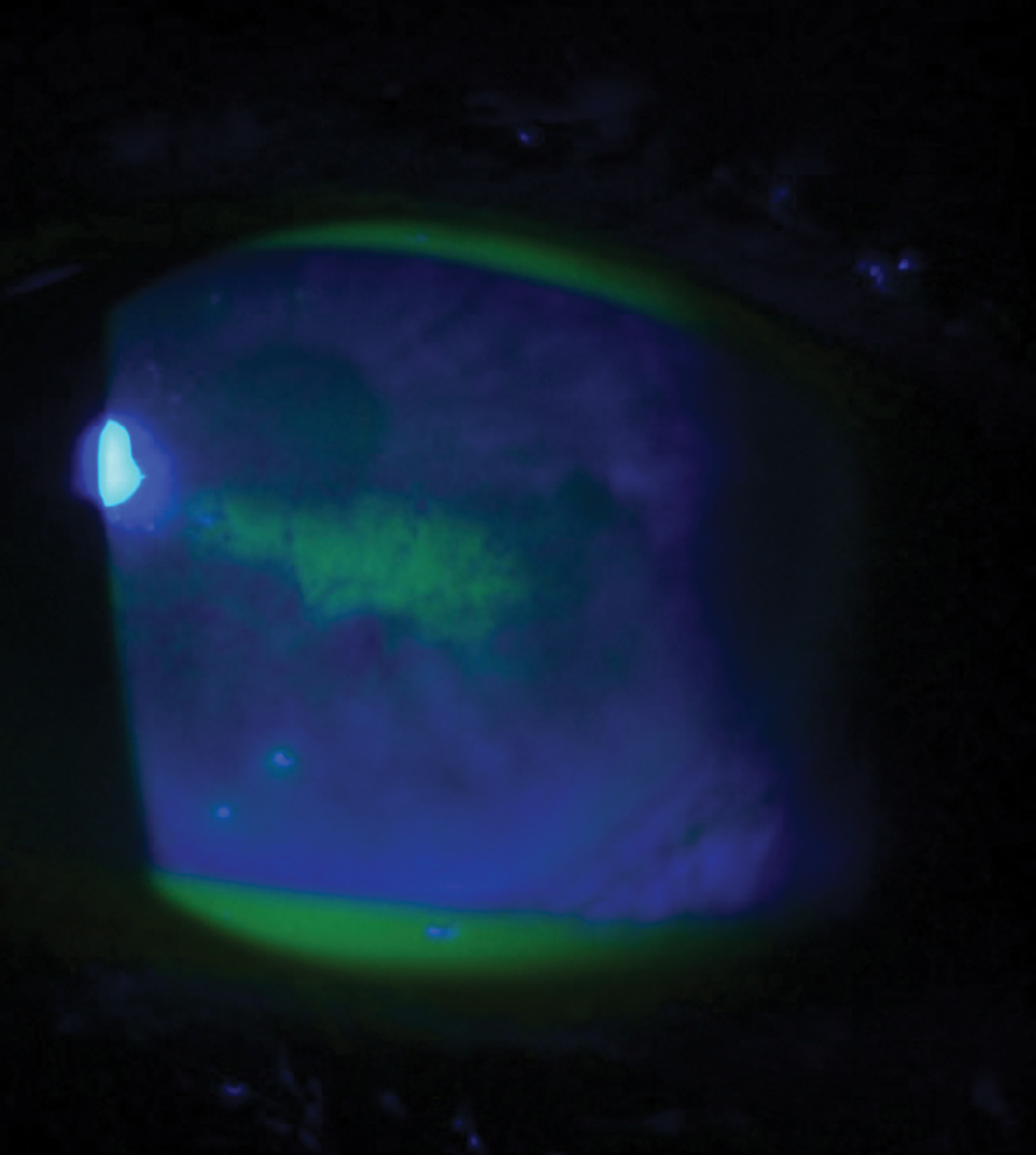

| Geographic ulcers can be more difficult to distinguish from other differentials. They are categorized by coalesced staining and dendriform characteristics along their edge margin. Photo by Lisa Marten, MD. Click image to enlarge. |

It is vital to document recent ocular surgeries, current and previous contact lens wear, a history of corneal abrasions or recurrent corneal erosions and any changes in recent systemic health. Furthermore, always note any recent episodes of fever, new or recurrent cold or nasal sores and any recent use of systemic and/or topical corticosteroids. Steroids in particular, without the use of an antiviral, can result in HSVK recurrence due to lowered immune system activity that allows for an increase in viral replication.

Symptoms of HSVK can vary from person to person and may depend on the degree and type of corneal involvement. Patients will often present with pain, foreign-body sensation, light sensitivity, watering, redness and blurred vision.2,4 In addition, HSVK is most commonly recognized as unilateral and should therefore be considered as a differential in any unilateral red eye or keratitis, regardless of pain. Bilateral HSVK is rare and is more likely to occur in children and patients who have experienced recent immunosuppression.5

Recognize and Prioritize

At the beginning of the clinical exam, always evaluate the patient’s ocular adnexa while they are sitting in the exam chair even before they are behind a slit lamp biomicroscope. Evaluation of the ocular adnexa can reveal signs related to other conditions that present with similar symptoms as HSVK. For example, HZV will often produce vesicles of the forehead, scalp and face that respect the vertical midline.4

Corneal sensitivity testing and a thorough slit lamp exam, which includes evaluation of the cornea and corneal staining, are key components in the diagnosis and management of HSVK. Corneal staining is a technique that uses fluorescein, lissamine green or rose Bengal stain to improve visualization of epithelial defects and virus-laden cells on the cornea. The hallmark sign of HSVK is a dendritic lesion with terminal bulbs. The main body of the lesion will stain with fluorescein while the terminal bulbs will stain with rose Bengal or lissamine green.4,6 This can be helpful especially in distinguishing HSVK from conditions such as HZV that produce pseudodendrites that result in negative staining and no terminal bulbs.

|

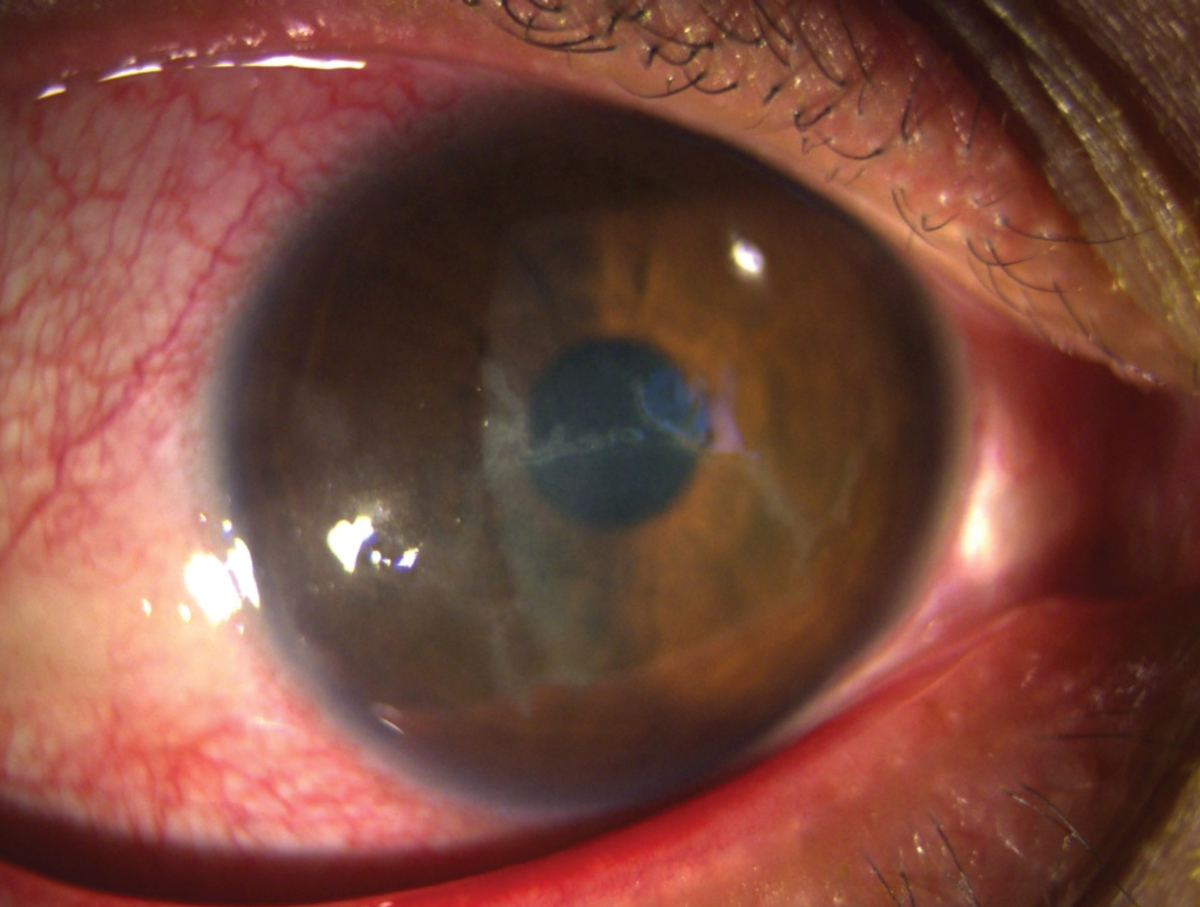

| Dendrites that stem from HSV epithelial keratitis can come in all shapes and sizes, ranging from small to those that encompass a large surface area of the cornea. Photo by Lisa Marten, MD. Click image to enlarge. |

Occasionally, the corneal lesions will be coalesced in appearance, making them slightly more difficult to diagnose. These more amoeba-appearing lesions are called geographic ulcers. However, even with their less distinguished appearance, these ulcers still usually have dendriform characteristics along their edge margin which can be visualized through corneal staining.6

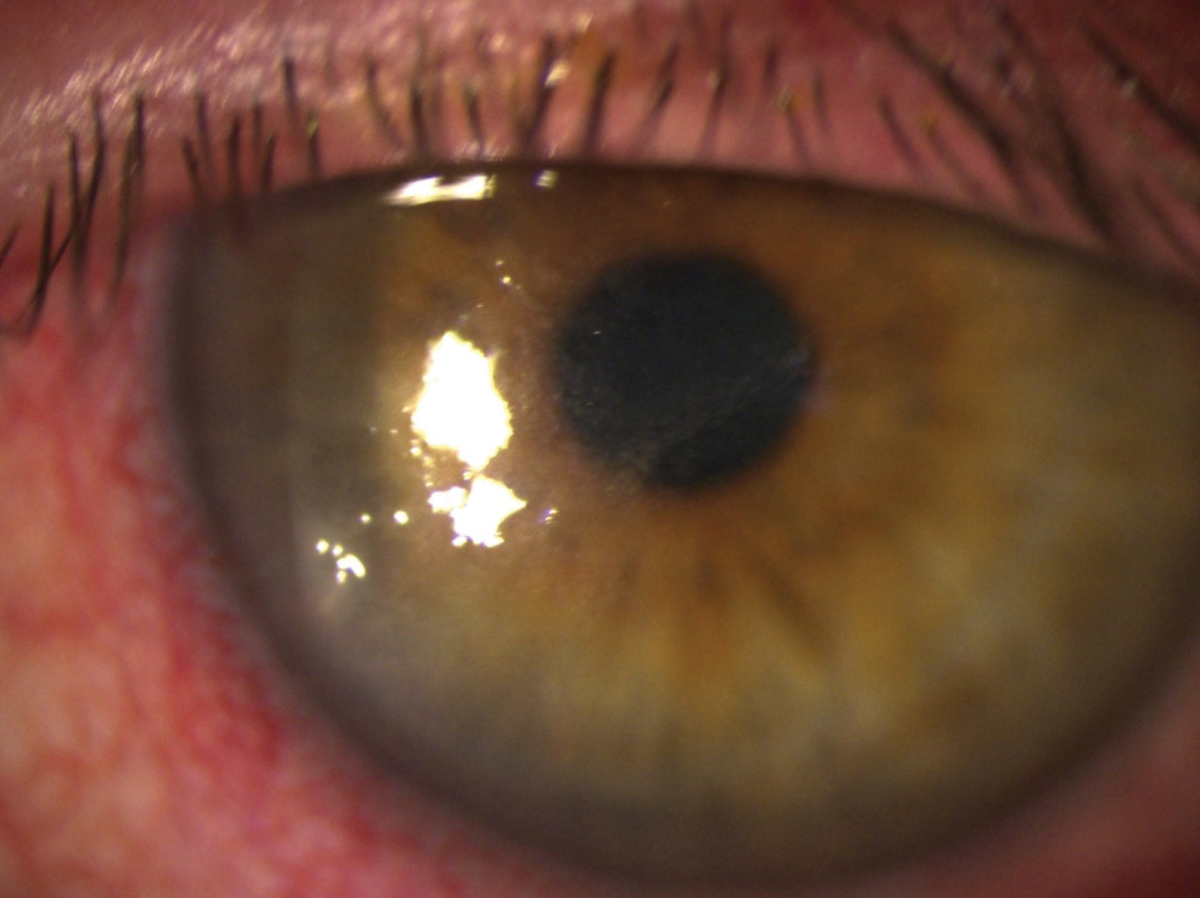

Although HSVK most commonly presents as an epithelial disease, recurrent infections can become both stromal and endothelial in nature.4 Distinguishing between the types of presentations is important as this can help determine which type and dosing of treatment should be administered. Unlike epithelial HSVK, stromal disease commonly presents with an eccentric lesion, stromal edema and anterior chamber reaction.4 This can result in stromal keratitis with or without epithelial ulceration, which can be determined through dye staining at the slit lamp biomicroscope. Alternatively, endothelial disease presents with endothelial inflammation, elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), keratic precipitates and disc-shaped corneal edema (i.e., disciform keratitis).5

Once corneal staining has been completed, it is important to check corneal sensitivity. Decreased corneal sensitivity can be a sequelae of HSVK, which results from damage to the corneal nerves and is especially common in patients with recurrent disease.4 This attribute of HSVK can be easily evaluated both behind the slit-lamp and in the exam chair by using a cotton whisp to evaluate blink reflex. Reduced blink reflex is a sign that corneal sensitivity is decreased and can help to rule out other differentials often marked by increased corneal sensitivity such as corneal abrasions, recurrent corneal erosions and microbial keratitis.

Clinical examination through slit lamp biomicroscopy combined with a thorough history is usually sufficient in diagnosing HSV keratitis.2 This typically makes laboratory testing and diagnostic testing unnecessary. However, diagnostic testing is available when the presentation is atypical and the clinical examination does not reveal easily diagnosed HSV ulcers and lesions.

Culturing is considered the standard in laboratory diagnosis of HSVK.5 Unfortunately, this is usually only useful when the disease is epithelial in nature since the virus typically cannot be cultured in cases of stromal or endothelial disease.5 Culturing generally results in outcomes that have high specificity but low sensitivity and long turn-around times.5 In addition, a virology laboratory is usually necessary to process the viral cultures, which can result in decreased availability to clinicians and increased diagnostic times.5

The other two most common diagnostic tests for identifying HSVK are direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). DFA allows for detection of HSV antigens while PCR detects viral DNA.5 Although both methods are highly sensitive and specific, they are limited by their need for trained technicians, expensive equipment and low availability.5

|

| Dendritic lesions that occur centrally can be visually detrimental. Even with treatment these ulcers may cause permanent vision loss due to scarring. Photo by Lisa Marten, MD. Click image to enlarge. |

Understanding The Differentials

One of the most difficult aspects of diagnosing, treating and managing patients with HSVK is the wide variety of presentations that can manifest. The list of differentials for HSV keratitis can vary based on whether the course of the disease is epithelial, stromal or endothelial in nature.

Epithelial differentials include conditions that cause dendritic and/or geographic-like lesions such as HZV keratitis, Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK), bacterial keratitis, recurrent corneal erosions, exposure keratopathy and tyrosinemia keratitis. AK in particular can cause a dendritic epithelial pattern that can be mistaken for HSVK.7 However, a clinician can garner distinguishing features by evaluating corneal staining (AK has no terminal bulbs) and patient history (AK is commonly contact-lens associated).7 Alternatively, conditions such as HZV keratitis and tyrosinemia keratitis produce pseudodendritic lesions that can be better defined by their staining pattern and corneal appearance.

For stromal and endothelial keratitis, the differential diagnosis list includes conditions that can cause interstitial keratitis as well as keratouveitis. This includes diseases such as syphilis, Cogan’s syndrome, Epstein-Barr virus, microbial keratitis, neurotrophic keratopathy, Posner-Schlossman syndrome and cytomegalovirus endothelial keratitis, among others.5

Many times, these conditions may be harder to separate, especially in cases where there is no epithelial ulceration. In some cases, laterality can help distinguish differentials, as is the case with Cogan’s syndrome and syphilis. In situations where the condition does not respond to treatment, additional laboratory testing may be necessary to rule out differentials.

Due to its prevalence and potentially devastating corneal outcomes, clinicians must consider HSVK as a possible diagnosis in any case of epithelial, stromal or endothelial keratitis.

Table 1. Recommended Dosing for HSV Epithelial Keratitis3,5,8 | ||

| Name | Administration Route | Recommended Dosage |

| Viroptic | Topical | 1gtt nine times a day for seven days then decreased to five times a day for seven days once ulcer is healed |

| Zirgan | Topical | 1gtt five times a day until ulcer is healed and then TID for seven additional days |

| Zovirax | Oral | 400mg five times a day for seven to 10 days |

| Valtrex | Oral | 500mg TID PO for seven to 10 days |

| Famvir | Oral | 250mg TID PO for seven to 10 days |

Treatment Approaches

Understanding the differences and ways in which HSVK can affect the ocular surface is important when approaching the treatment of each patient. Guidelines exist for the care and management of patients with HSVK; however, the types of medications and their dosages depend on the specific disease process. This means that clinical treatment will vary based on whether the HSVK is epithelial, stromal or endothelial.

Treatment of HSVK is divided into three main components: topical antiviral, oral antiviral and topical corticosteroids. There are currently three topical antivirals approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of HSV keratitis. The two most common are Viroptic (trifluridine 1%, Pfizer) and Zirgan (ganciclovir 0.15%, Bausch + Lomb). The third, Avaclyr (acyclovir ophthalmic ointment 3%, Fera) was approved by the FDA in April 2019, but commercial launch appears to still be pending based on the company’s website.

In addition to the topical variations, oral antivirals are widely and commonly used off label to treat HSV keratitis.5 The three most common agents are Zovirax (acyclovir, GlaxoSmithKline), Valtrex (valacyclovir, GlaxoSmithKline) and Famvir (famciclovir, Novartis). Choosing between topical or oral antivirals as well as whether or not an adjunct topical corticosteroid is necessary depends on which portion of the ocular surface is affected and the type of patient you are treating.

Herpes simplex epithelial keratitis. The most common form of HSVK disease, HSV epithelial keratitis is characterized by the hallmark dendritic lesion or geographic ulcer without stromal or endothelial involvement. Research suggests combining both oral antiviral and topical therapy is not necessary in the treatment of epithelial HSVK. The Herpetic Eye Disease Study (HEDS) I noted no benefit from adjunct therapy in the average HSVK patient, so maintaining one course of treatment is ideal from both a time and cost perspective.8

Oral antivirals are the treatment of choice when managing HSV epithelial keratitis. They are typically more affordable for patients and have a more adaptable dosing schedule. The three most common oral antiviral agents, acyclovir, valacyclovir and famciclovir, are all dosed at different intervals. Acyclovir is dosed 400mg five times daily for seven to 10 days, valacyclovir is dosed 500mg three times daily for seven to 10 days and famciclovir is dosed 250mg three times daily for seven to 10 days. Valacyclovir, specifically, is a great option since it is generally well tolerated and has a reduced dosing schedule. There is also some evidence that it may have superior ocular penetration (Table 1).8

Topical antiviral usage and dosage vary based on availability, timing during the course of the condition and affordability. Topical antivirals are often reserved for patients who cannot use oral antivirals due to systemic health or other limitations.

Viroptic is typically dosed at one drop in the affected eye nine times daily for seven days and then decreased to five times daily for seven days if the ulcer is healed, whereas Zirgan is dosed at one drop into the affected eye five times daily until the ulcer is healed and then three times daily for an additional seven days.3,5,8

Both medications have their own advantages and disadvantages.3,5,8 Viroptic is generally more affordable, but is considered toxic to the ocular surface at prolonged exposure and therefore must be limited to just 21 days of use.5 Zirgan is better for children as well as patients who require prolonged treatment but is often considered a more expensive therapy.5

Choosing between an oral and topical antiviral will likely depend on the patient. Oral antivirals should be used cautiously in patients with known kidney or liver disease due to metabolism of the active drug. When choosing oral antivirals always alert patients to possible side effects, and whenever in doubt discuss with the patient’s primary care physician before prescribing.

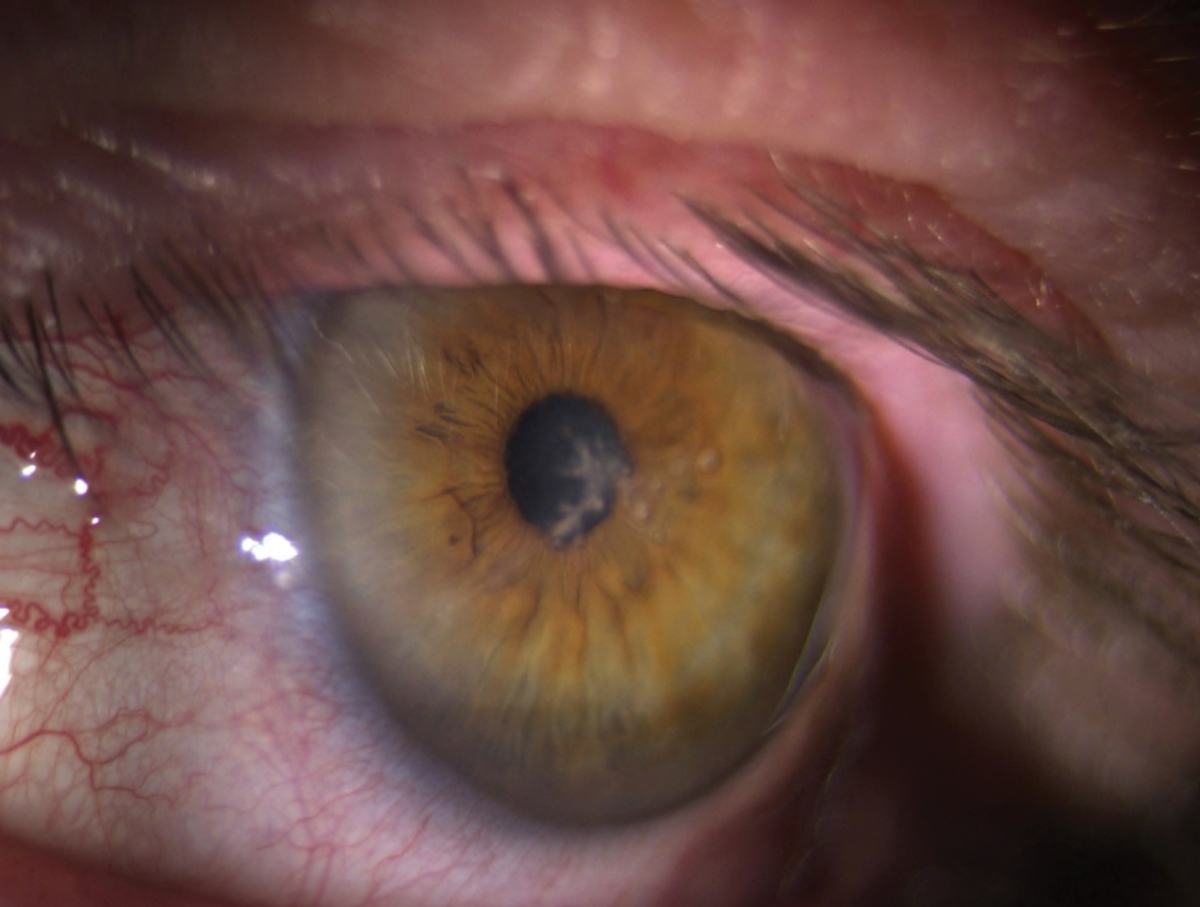

|

| HSV endothelial keratitis is unique because it can occur with or without prior HSVK clinical manifestation. Photo by Lisa Marten, MD. Click image to enlarge. |

HSV stromal keratitis (with and without ulceration). Unlike HSV epithelial keratitis, HSV stromal keratitis is considered an immune-mediated response resulting in inflammation of the ocular tissue. It is thought to be secondary to the viral particles from the initial epithelial infection that persist in latent or active states in the corneal stroma.3 When HSV stromal keratitis presents without ulceration, this means that necrosis of the stromal tissue has not yet occurred and ulceration of the stromal bed is not present.5,8,9

Rarely, instead of signaling an inflammatory response, the cells progress to necrosis of the tissue, which can then result in thinning of the corneal tissue and increased risk of corneal perforation.5,8,9 This is known as HSV stromal keratitis with ulceration. Fortunately, HSV stromal keratitis without ulceration is the more common presentation of the two forms.

Treatment of stromal keratitis is directed at controlling both the viral and inflammatory response. This is achieved via the combination of an oral antiviral and a topical corticosteroid.3 Combination therapy should be applied for at least 10 weeks, and the balance and taper regimen can be adjusted based on the corneal appearance.5 This ultimately means that the taper period of the steroid may be longer depending on how the patient responds to therapy.

For patients with stromal keratitis, oral antivirals are recommended over topical due to their safety profile (i.e., length of use) and superior corneal penetration.5 Throughout therapy, as long as a patient is on a topical corticosteroid they must also be on an antiviral agent.

HSV endothelial keratitis. This condition is a cell-mediated immune reaction to corneal endothelial tissue that results in persistent corneal edema and inflammation.5 Endothelial keratitis is unique compared with other forms of HSVK because it can occur independent of epithelial or stromal keratitis.5 In fact, in up to half of reported cases of HSV endothelial keratitis the patient has no prior history of HSV epithelial keratitis.

A combination of oral antiviral and topical corticosteroid are considered the mainstay of treatment for this condition.5 Unlike stromal keratitis, endothelial keratitis responds more rapidly to treatment, resulting in shortened therapy time and disease course.5 As with all forms of HSVK, management and taper is dependent on the patient’s response to medication and may vary among individuals.

|

| HSV stromal keratitis is considered an immune-mediated response resulting in inflammation of the ocular tissue. It is characterized by inflammation of the stromal bed. Photo by Lisa Marten, MD. Click image to enlarge. |

Prognosis and Prophylaxis

For patients who suffer from recurrent disease or are at increased risk of recurrence, prophylaxis can help decrease the incidence of stromal scarring, vascularization and minimize poor visual outcomes. The HEDS II study found that the prophylactic use of an oral antiviral could reduce reactivation by 45% compared with the placebo group.8 Therefore, prophylactic dosing of oral antiviral agents is indicated in patients with higher risk of reactivation.

The recommended dosing varies between antivirals but includes acyclovir 400mg twice daily for at least one year, valacyclovir 500mg once daily for at least one year or famciclovir 250mg twice daily for at least one year.5 Prophylactic dosing does not have to end after one year, especially if the patient has a prolonged increased risk of reactivation; but at least one year of dosing is recommended.

In many cases, clinician vigilance and early recognition of HSVK can help prevent many of the devastating corneal outcomes. However, sometimes due to the severity of the disease or other prognostic factors (i.e., lack of symptoms in smoldering disease, which can delay treatment), corneal scarring and poor visual prognosis cannot be avoided. In these cases, it is important to manage outcomes and educate patients on visual expectations. This may require eventual application of an amniotic membrane to improve corneal scarring, fitting of specialty lenses to reduce visual distortion or referral to a corneal specialist for further surgical intervention.

The Bottom Line

HSV keratitis undoubtedly can be difficult to recognize, treat and manage. With its propensity for high seroprevalence in the population along with its ability to masquerade as other corneal diseases, it is important for clinicians to recognize the signs and symptoms of this condition quickly. By having a thorough understanding of the disease process, its clinical presentation and the necessary treatment, we can further reduce poor visual prognoses and be better advocates for our patients. Ultimately, in any corneal or ocular surface condition that presents to your clinic, always be on the lookout for red flags and HSV hallmarks.

The author would like to thank Lisa Marten, MD, of South Texas Eye Institute, for the images.

Dr. Leon practices at the South Texas Eye Institute in San Antonio. She is a graduate of the Rosenberg School of Optometry where she completed both her optometry degree and her residency in Primary Care.

1. Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57(5):448-62. 2. Azher T, Yin XT, Tajfirouz D, et al. Herpes simplex keratitis: challenges in diagnosis and clinical management. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:185-91. 3. Lobo AM, Agelidis AM, Shukla D. Pathogenesis of herpes simplex keratitis: The host cell response and ocular surface sequelae to infection and inflammation. Ocul Surf. 2019;17(1):40-9. 4. Ahmad B, Patel BC. Herpes simplex keratitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. 5. White ML, Chodosh J. Herpes simplex virus keratitis: a treatment guideline–2014. American Academy of Ophthalmology Clinical Guidelines. www.aao.org/clinical-statement/herpes-simplex-virus-keratitis-treatment-guideline. Accessed October 6, 2020. 6. Weiner G. Demystifying the ocular herpes simplex virus. American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2013. www.aao.org/eyenet/article/demystifying-ocular-herpes-simplex-virus. Accessed October 6, 2020. 7. Acanthamoeba keratitis often mistaken for herpes simplex. Rev Optom. 2007;144(8). 8. Austin A, Lietman T, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Update on the management of infectious keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(11):1678-89. 9. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Herpes Simplex Keratitis - Europe. 2013. www.aao.org/topic-detail/herpes-simplex-keratitis--europe. Accessed October 6, 2020. |