|

A 90-year-old Caucasian male presented complaining of chronic irritation and soreness in his right eye (OD). His ocular history was significant for pseudoexfoliative glaucoma OD>OS, status post-SLT, followed by a trabeculectomy with mitomycin OD in 2016. In 2018, he underwent a vitrectomy, intraocular lens exchange and Ahmed glaucoma valve OD, followed by a central retinal vein occlusion for which he received monthly intravitreal injections OD. His entering uncorrected acuity was 20/800 OD, 20/60 OS. He was taking Lumigan.

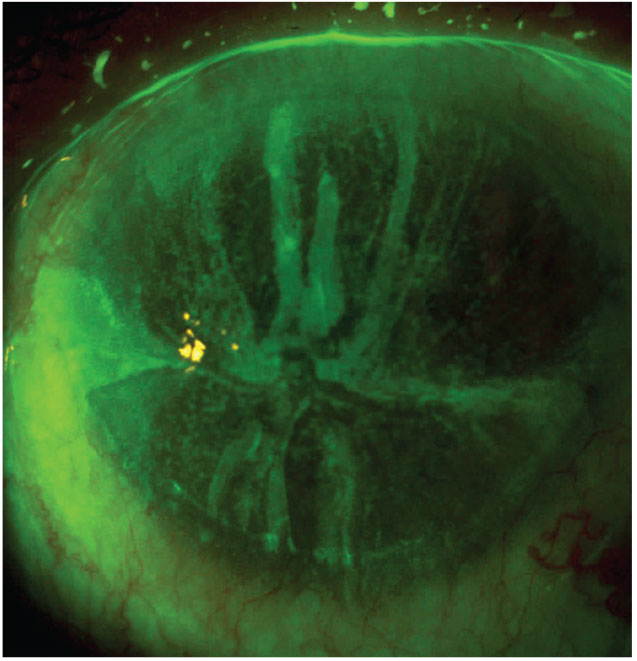

On slit lamp exam he had meibomian gland dysfunction, a superior temporal trabeculectomy and suture. The cornea had whorl staining, superior filaments and inferior superficial punctate keratitis (Figure 1). The filaments were debrided and Prokera Slim was inserted OD. The patient reported relief in his symptoms for one to two months until he returned with irritation. At this time, he was given the options of another amniotic membrane, bandage contact lens, scleral shells or initiation of a low-grade steroid. After speaking with his glaucoma specialist, loteprednol etabonate 0.5% QID was started; however, the patient received no relief. Due to his age and dexterity, he was not comfortable using a scleral shell and opted to have a monthly bandage contact lens inserted.

Diagnosis

The patient underwent trabeculectomy with mitomycin C for glaucoma, which uses a technique that is fornix-based conjunctival incision and leaves the of damaging cells at the limbus.1,2 5-Fluorouracil and mitomycin C (MMC) are often used, which are cytotoxic drugs applied to the sclera during surgery.

Limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) has been reported after the use of topical MMC, and it’s been proposed that dry eye disease after trabeculectomy supplemented with MMC is due to LSCD.1,3 Therefore, this patient has an iatrogenic cause of LSCD.

|

Fig. 1. This patient has fluorescein staining with an evident whorl pattern. Click image to enlarge. |

LSCD

The Limbal Stem Cell Working Group formed by the Cornea Society defines LSCD as “an ocular surface disease caused by a decrease in the population and/or function of corneal epithelial stem/progenitor cells; this decrease leads to the inability to sustain the normal homeostasis of the corneal epithelium.”4

Limbal stem cells are essential in maintaining the normal homeostasis of the corneal epithelium, resulting in a transparent cornea and opaque sclera. The limbus and limbal stem cells act as a barrier against invasion of unwanted conjunctival epithelial cells onto the cornea. The process of differentiation of the limbal stem cells occurs by transit-amplifying cells. These have a controlled ability for self-renewal and undergo a limited number of cell divisions. Around 25% to 33% of the limbus must be intact in order to guarantee normal ocular resurfacing. When there is a deficiency, a pathological condition results in the dysfunction or inadequate quantity of limbal stem cells, resulting in migration of conjunctival cells onto the ocular surface.5

LSCD results from either a primary (genetic) or secondary insults. The etiology can be classified into six categories: idiopathic, traumatic, iatrogenic, autoimmune, eye disease and congenital/ hereditary.5,6

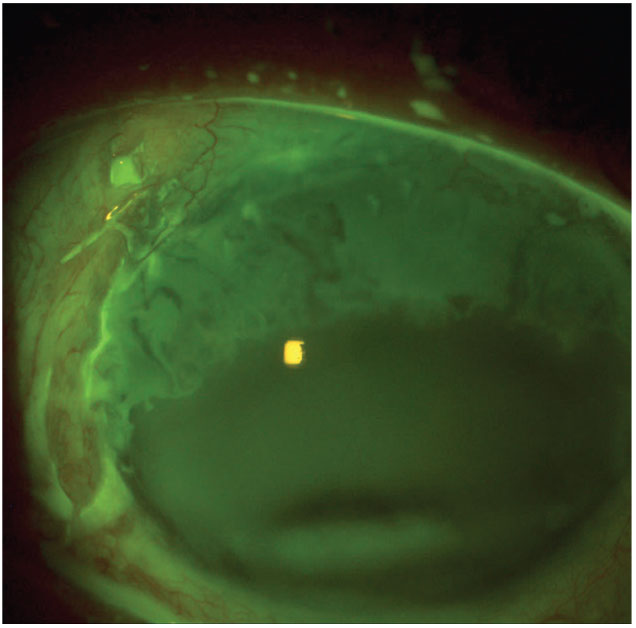

Patients may initially be asymptomatic. Those experiencing symptoms may describe ocular discomfort, irritation, conjunctival redness, dryness, photophobia, decreased vision, foreign body sensation and tearing.4 The common clinical findings of LSCD are recurrent ulceration, decreased vision, corneal neovascularization and wavelike irregularity of the ocular surface emanating from the limbus. The wavelike irregularity is usually seen emanating from the limbus and can be observed easiest when fluorescein is instilled (Figure 2).6 Diagnostic tests used for detection include impression cytology, in vivo confocal microscopy and AS-OCT of the cornea and limbus.1

Partial LSCD is characterized by a sectoral conjunctivalization of the corneal surface, the presence of residual limbal and consequent corneal epithelial cells. Total LSCD is described as conjunctivalization of the entire cornea due to complete loss of corneal epithelial stem/progenitor cells.4

The Cornea Society created this classification for staging LSCD:

Stage I: normal corneal epithelium within the central 5mm zone of the cornea.

(a) less than 50% of limbal involvement

(b) more than 50% but less than 100% limbal involvement

(c) 100% of limbal involvement

Stage II: central 5mm zone of the cornea is affected.

(a) less than 50% of limbal involvement

(b) more tan 50% but less than 100% limbal involvement

Stage III: the entire cornea is affected.4

Another way to classify LSCD is mild, moderate and severe. Mild findings include a dull/irregular cornea surface, corneal epithelial opacities, loss of limbal palisades of Vogt. Moderate findings include abnormal epithelium causing fluorescein staining and a vortex pattern that can be visualized. These patients might be more prone to erosions and have underlying mild anterior stromal haze. Superficial neovascularization and peripheral pannus may be present at this stage. If the central visual axis is involved, patients may report decreased vision. Severe findings include persistent corneal epithelial defects, corneal stromal scarring and corneal neovascularization.5

|

Fig. 2. This patient post-trabeculectomy is treated with mitomycin C. Click image to enlarge. |

Management

The approach to treating LSCD differs depending on the level of severity. For all cases, if possible the inciting cause should be discontinued, such as contact lenses or topical medications. For mild cases, a low-grade topical steroid may be helpful. If the LSCD is focal, consider debridement and allow for resurfacing from healthy intact limbal epithelium.5,6 A limbal or conjunctival autograft can be considered. Options for severe or extensive cases include an amniotic membrane, bandage contact lens, scleral contact lens or a limbal transplant.

Non-surgical treatments include:

- Autologous serum drops. Promotes migration and proliferation of a healthy epithelium, and improves lubrication of the epithelial surface.

- Therapeutic bandage contact lens. Prevents new epithelial defects and promotes healing.

- Therapeutic scleral lens. Promotes corneal healing while improving vision. Reduces pain and photophobia, and prevents new corneal epithelial defects.

- Lubrication. Prevents epithelial adhesion and shear stress.

Conservative surgical options include:

- Corneal scraping. Removes overgrown conjunctival enabling reepithelization of function corneal epithelial stem cells.

- Amniotic membrane transplantation. Promotes proliferation and migration of limbal epithelial stem cells.

Limbal epithelial stem cell transplantation includes conjunctival limbal autograft, conjunctival limbal allograft and keratolimbal allograft.7

LSCD is a condition that is in our clinics daily, which is why keeping it as part of your differential for patients who are asymptomatic to symptomatic is important. Currently, diagnostic materials and criteria are based on clinical examination and impression cytology. In the future, the characterization of cellular structure of the healthy cornea and limbus will come more into play with advancements using molecular markers.

1. Muthusamy K, Tuft SJ. Iatrogenic limbal stem cell deficiency following drainage surgery for glaucoma. Can J Ophthalmol. 2018;53(6):574-9. 2. S Hau, K Barton. Corneal complications of glaucoma surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20(2):131-6. 3. J Lam, TT Wong, L Tong. Ocular surface disease in posttrabeculectomy/mitomycin C patients. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:87-91. 4. Deng SX, Borderie V, Chan CC, et al. Global consensus on definition, classification, diagnosis and staging of limbal stem cell deficiency. Cornea. 2019;38(3):364-75. 5. Le Q, Xu J, Deng SX. The diagnosis of limbal stem cell deficiency. Ocul Surf. 2018;16(1):58-69. 6. Schwartz GS, Holland EJ. Classification and staging of ocular surface disease. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, edu, Cornea. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Mosby. 2011;1713-20. 7. Haagdorens M, Van Acker SI, Van Gerwen V, et al. Limbal stem cell deficiency: current treatment options and emerging therapies. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:9798374. |