|

Given the possibility of profoundly negative outcomes when dealing with microbial keratitis (MK), careful consideration is critical when deciding what initial treatment is appropriate. Prescribing a standard medication across all ulcer appearances and histories is a sure-fire way to eventually end up with a terrible outcome. For this reason, mining the case for clues of the most likely etiology and treating appropriately is a mandatory part of corneal ulcer care.

While sensitivity testing can help tailor the treatment for the specific organism, all antimicrobial treatment begins empirically since getting results back from a culture can take anywhere between one and seven days (unless you perform in-house gram stain interpretation). As such, the onus is always on the clinician to select the most appropriate initial treatment.

The Paradigm Shift

Over the last 20 years, we’ve been fortunate to practice in an era of relatively effective antimicrobial monotherapy. Fluoroquinolones are an effective treatment tool for most common etiologies of bacterial corneal infection—and while original coverage favored gram-negative pathogens, newer generations have expanded to cover gram-positive pathogens as well. This allows care delivery to move away from the cornea clinic standard of care (dual broad-spectrum fortified agents) to a single agent that is undoubtedly easier to acquire and prescribe. As a result, monotherapy now predominates the management of corneal ulcers across the United States.

What’s more, this shift has not led to any poor outcome trends, and in most cases, fluoroquinolone monotherapy has been effective. Research shows that single new-generation fluoroquinolones may be just as effective as dual broad-spectrum antibiotics, and one recent meta-analysis in particular shows no difference in treatment success, time to heal or risk of severe complication between the two.1 The study also found no difference among the various fluoroquinolone agents, suggesting that ofloxacin may be as effective as moxifloxacin, and both may be as effective as dual fortified agents.

A caveat exists in applying this data universally, however, in the form of antibiotic resistance by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE). Based on data from both the Ocular TRUST 2 and ARMOR studies, we know that occurrences of MRSA and MRSE isolates are on the rise in the United States and that in vitro fluoroquinolones aren’t terribly effective against them.2,3 The studies reviewed by the aforementioned meta-analysis suffer from a few similarities that makes them difficult to directly apply to clinic with today’s resistance trends.

First, the studies in this review are drawn from across the globe, but distribution of micro-organisms varies widely from region to region—as would be the case for MRSA and MRSE incidence. Therefore, studies from Thailand or India may not necessarily apply to a United States cohort, and expecting the results to tell us something about a problem as specific as antibiotic resistance in the United States is flawed thinking.

Second, nearly all of the US studies reviewed in the meta-analysis predate the ARMOR study, the Ocular TRUST 2 or both. Those two studies should serve as the ground floor for gram-positive resistance trends, which are most likely expanding.

Because of these issues, I believe that while monotherapy is still appropriate as frontline therapy for many bacterial corneal ulcers, it may be inappropriate in other cases such as co-infection, non-bacterial and resistant organisms despite support from research.

|

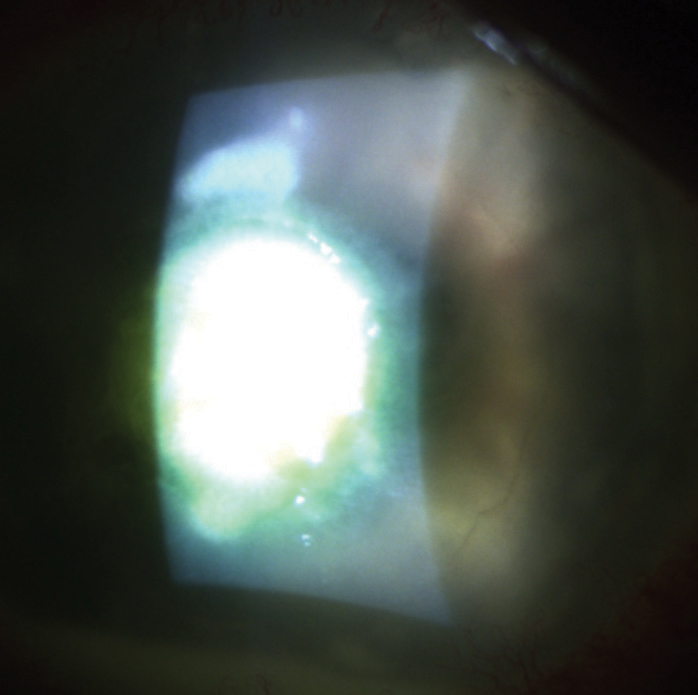

| Initial treatment for ulcers that are Staphylococcal in origin should be adjusted for the possibility of antibiotic resistance. Photo: Scott G. Hauswirth, OD, and Richard Mangan, OD |

Making the Call

When deciding whether you want to proceed with initial fluoroquinolone monotherapy or pair it as a dual therapy, you should consider the most likely source of infection. Though it’s impossible to fully differentiate ulcers based on clinical appearance and their supportive history, it is still possible to get down to some general assumptions.

We know that resistance to fluoroquinolones among gram-negative pathogens is a relatively rare phenomenon and that these medications work exceptionally well as monotherapy among this group. For that reason, fluoroquinolone monotherapy would be reasonable for ulcers that support a conclusion of likely gram-negative involvement (i.e., those that look wet and mucousy and those with a contact lens history).

However, ulcers occurring as a result of ocular surface disease, in elderly patients, in those with rheumatoid arthritis or with a dry-looking infiltrate are more likely to be Staphylococcal in origin, so treatment should be adjusted for the possibility that an antibiotic resistant isolate may be causative. This doesn’t necessarily require a move to fortified agents, however.

According to Ocular TRUST 2, a handful of commercially available agents such as trimethoprim/polymyxin B, aminoglycosides and bacitracin may be useful against these ulcers when paired with a fluoroquinolone. This gives you good coverage across a broad spectrum, including potential resistant organisms.2 It should be noted, however, that bacitracin ointment may be useful to limit the need for multiple nighttime doses, but probably shouldn’t be used as paired therapy during the day because it may reduce penetration of other antimicrobial agents.

When deciding on the initial dosage, the severity of the ulcer you’re dealing with will play a role—but again, it’s possible to make some general recommendations. First, all antibiotics are concentration dependent, so the initial goal is to raise the local tissue concentration of the antibiotic to levels as high as possible. This requires a series of in-office loading doses every five to 15 minutes to rapidly achieve high stromal concentrations.

After this, instruct the patient to use the drop regularly, generally on an hourly basis during the day and every one to two hours at night. Again, the goal here is to maintain the elevated tissue concentration first achieved with the loading dose. If dual agents are required, we generally recommend they be used on alternating hours or half hours (if the ulcer is severe) during the day and then paired together during nighttime dosing.

Carefully considering all facets of the case to help select the most appropriate initial therapy will improve your comfort in managing these cases and, perhaps, the outcomes you achieve. However, initial therapy is still, at best, based on educated guesses about the etiology, so close follow-up is necessary to confirm your “best guess treatment” was appropriate.

Follow-up should be performed daily until signs of improvement are noted, at which point the antibiotic dosing and frequency of follow-up should each be reduced in a stepwise fashion with continued improvement. In the face of treatment failure (i.e., the ulcer worsening over two days or not improving over several days), the only categorically inappropriate step would be continuing with the current therapy. Signs of worsening should be taken as indicative of treatment failure and the practitioner should consider culturing/re-culturing, referral or empiric treatment change.

While much research explores initial treatment options for MK, monotherapy with fluoroquinolones is no less effective then dual therapy. The influence of resistance on this strategy has not been fully explored. So, for each corneal ulcer, regardless of the culturing strategy, practitioners should scrutinize the elements of the case—including clinical appearance, history and response to any previous treatments—that may suggest one infectious etiology over another and consider how likely that etiology is to be resistant to fluoroquinolones prior to initiating empiric therapy.

1. McDonald EM, Ram FS, Patel DV, McGhee CN. Topical antibiotics for the management of bacterial keratitis: an evidence-based review of high quality randomized control trials. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(11):1470-7. |