|

Though familiar corneal pathogens, such as Staphylococcus epidermidis and aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, cause the majority of ulcers clinicians see, a small percentage are caused by protozoan and fungal etiologies. Of these atypical microbial keratitis sources, fungal origins are encountered most frequently and have a worse prognosis than many other corneal infection sources. A number of fungal species that cause corneal infection only cause one disease—keratitis—and haven’t been documented to cause infection anywhere else in the body.1 This illustrates how the cornea is perfect for incubating fungal infections; it’s a warm, damp environment isolated from the immune response—a fungal infection trifecta. This column will review this group of pathogens and the challenges they present.

A Gloomy Forecast

The incidence of fungal keratitis varies based on geographic location. In the northern temperate and southwestern desert parts of North America, the incidence is relatively low, accounting for 6% to 10% of all ulcers encountered, whereas in tropical parts of the continent, the incidence approximately doubles.2-5

The prognosis of fungal keratitis is startling; 43% of emergent keratoplasties performed out of Bascom Palmer are fungal keratitis surgeries, though the incidence is about 20% in Southern Florida—meaning that fungal keratitis is more than twice as likely as bacterial keratitis to lead to emergent transplant.5,6

Many reasons for this negative prognosis exist, including limited, poorly penetrating ophthalmic preparations of antifungal medication. Perhaps more important is the missed opportunity for early recognition of fungal keratitis due to a lack of knowledge about the infection’s risk factors.

Look at the Big Picture

Fungal keratitis is widely associated with organic trauma—the most frequent risk factor for fungal disease across the globe.1 Unfortunately, the index of suspicion drops when the historic risk of trauma is absent. Organic trauma, however, is not the only cause, and clinicians should consider other risk factors when weighing the likelihood of a fungal ulcer. One study found that while 25% of fungal ulcers were associated with trauma, 37% were associated with contact lens use and 29% with opportunistic infections in patients with ocular surface disease (OSD).7 Though the study notes the percentage of cases associated with contact lens use dropped after an offending cleaner was pulled from the market, lens use is still associated with approximately as many cases of fungal keratitis as trauma.7,8

More perplexing is the association with OSD. While clinicians are often more concerned about members of the normal ocular flora and less about atypical etiologies, they should also remember that fungal elements can be components of the normal flora and cause opportunistic corneal infection in patients with OSD.7,8 In fact, yeast sources of fungal keratitis predominate in cases related to OSD, exposure and ophthalmic surgery.7,8

|

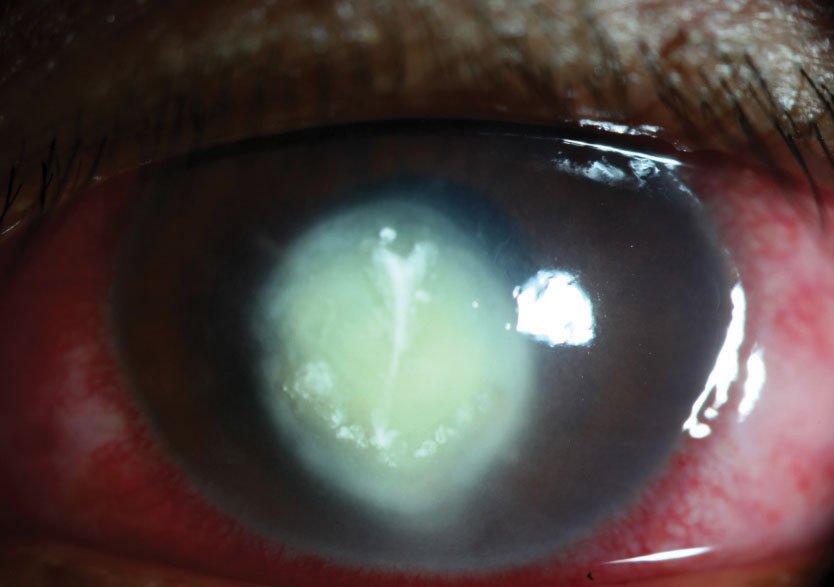

| Despite the absence of classic clinical findings, this severe corneal ulcer is fungal in nature. |

Keep Your Eyes Open

Clinicians may also assume fungal ulcers can be differentiated by their clinical appearance. Fungal ulcers are known to have a number of supposed “classic findings,” such as feathery margins, satellite infiltrates, pigmented infiltrates and endothelial plaques, that doctors can lean on to achieve a timely diagnosis. Unfortunately, nearly 60% of fungal ulcers do not have any classic clinical features related to fungal keratitis. When a lack of findings characteristic of fungal keratitis is paired with mundane risk factors, such as contact lens use and OSD, it is no wonder fungal keratitis is frequently misdiagnosed and wrongly managed as bacterial keratitis. One study suggests that nearly 90% of the fungal ulcers reviewed were originally being treated for bacterial keratitis.9 Given this finding, it is important to understand how to develop appropriate clinical suspicion regarding fungal keratitis.

Is it Fungal or Bacterial?

An article on Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) notes that the initial step in diagnosing AK is to suspect it.10 This mindset holds true when dealing with fungal keratitis as well; a more varied set of risk factors and a vaguer clinical appearance than classic cases leads to delays in diagnosis and treatment for a condition that already has a greater risk of surgical treatment. Keeping a fungal etiology somewhere on your differential until you achieve treatment success or receive culture results is critical to prevent further delays in diagnosis.

While culturing is important in the diagnosis of fungal keratitis, it isn’t always timely; fungal cultures can take nearly a month to produce a definitively negative result, thus, it is important to consider the possibility that you may be dealing with a fungal pathology when treating a microbial keratitis, even without a positive culture. This doesn’t mean that clinicians should start each patient who has a corneal ulcer on an antifungal, but until a positive response to therapy is observed or a culture result is obtained, clinicians need to at least consider the possibility that they may be dealing with a fungal ulcer, especially if the ulcer worsens after initial treatment.

This further illustrates the importance of aggressively treating infections with modern, broad-spectrum or fortified agents as initial therapy. If an unspecified ulcer is treated with a dated antibiotic QID and doesn’t respond, no clinically relevant conclusion can be drawn from that treatment failure. However, if initial treatment with a modern, broad-spectrum agent fails, fungal keratitis suddenly becomes a more reasonable etiology to suspect. Your initial treatment should be valuable, even if it eventually fails.

Going the Distance

When starting therapy for a fungal ulcer, there is only one commercially available topical antifungal, Natacyn (natamycin 5%, Novartis), that exists—all others must be compounded. The medication has reasonable efficacy against filamentous fungal pathogens but doesn’t perform as well against yeasts. In these cases, clinicians can use fortified AmBisome 1.5mg/ml (amphotericin B, Gilead Sciences) or fortified Vfend (voriconazole 1%, Pfizer). All topical antifungals can be paired with oral agents, particularly in cases of deep keratitis where penetration of the topical agent is a concern, but tolerance can be an issue with systemic antifungals.

Fungal ulcers are generally typified by a lower grade of inflammation than their bacterial counterparts, the clinical manifestation of which is the ulcer’s ability to deepen despite the epithelium healing over the ulcer bed. In most microbial keratitis cases, stromal inflammation precludes epithelial healing, which is why most of these ulcers have epithelial defects equal in size to their infiltrates. Stromal inflammation in fungal keratitis, however, can be mild enough that the epithelium may heal despite the active underlying infection. This further lowers stromal concentrations of antifungals and subsequently reduces their effectiveness, making it necessary to debride fungal ulcers to make topical medications more successful.

Fungal sources are also characterized by an indolent course. While the slow metabolic rate typical of fungal organisms reduces the rate of proliferation and spread, it also causes a slow response to therapy; full recovery may take several months, with the final treatment in a disproportionately high number of cases being therapeutic keratoplasty.

Given the varied risk factors and clinical appearances of fungal keratitis, diagnosis can be very difficult. Therefore, it is critical that a clinician keeps fungal keratitis in the back of their mind until they receive culture results or a patient responds positively to treatment. Doctors who are uncomfortable caring for true or suspected cases of fungal keratitis should promptly refer these patients to a cornea service.

|

1. Alfonso EC, Rosa RH, Miller D. Fungal keratitis. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, eds. Cornea. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2004:1043-74. 2. Lichtinger A, Yeung SN, Kim P, et al. Shifting trends in bacterial keratitis in Toronto: an 11-year review. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(9):1785-90. 3. Ni N, Nam EM, Hammersmith KM, et al. Seasonal, geographic and antimicrobial resistance patterns in microbial keratitis: 4-year experience in eastern Pennsylvania. Cornea. 2015;34:296-302. 4. Sand D, She R, Shulman IA, et al. Microbial keratitis in Los Angeles: the Doheny Eye Institute and the Los Angeles County Hospital experience. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(5):918-24. 5. Liesegang TJ, Forster RK. Spectrum of microbial keratitis in south Florida. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;90(1):38-47. 6. Amescua G, Miller D, Alfonso EC. What is causing the corneal ulcer? Management strategies for unresponsive corneal ulceration. Eye (Lond). 2012;26(2):228-36. 7. Keay LJ, Gower EW, Iovieno A, et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of fungal keratitis in the United States, 2001-2007: a multicenter study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(5):920-6. 8. Williamson J, Gordon AM, Wood R, et al. Fungal flora of the conjunctival SAC in health and disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1968;52:127-37. 9. Yildiz EH, Abdalla YF, Elsahn AF, et al. Update on fungal keratitis from 1999-2008. Cornea. 2010;29(12):1406-11. 10. Hammersmith KM. Diagnosis and management of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17(4):327-31. |