Corneal Ulcers: Sterile But Not Benign

Even if they aren’t infectious, these are no laughing matter. In fact, many ocular and systemic conditions might be at play.

By Elizabeth Escobedo, OD, and Nate Lighthizer, OD

Release Date: September 15, 2018

Expiration Date: August 16, 2021

Goal Statement: While practitioners often concern themselves with infectious etiologies of corneal ulcers, it is imperative they be just as familiar with the possible causes of sterile ulcers and know how to differentiate between the two presentations, as the treatments can differ drastically. This discussion zeroes in on the different types of non-infectious ulcers and reviews their etiologies, presentations and treatments.

Faculty/Editorial Board: Elizabeth Escobedo, OD, and Nate Lighthizer, OD

Credit Statement: This course is COPE approved for 1 hours of CE credit. Course ID is 58984-AS. Check with your local state licensing board to see if this counts toward your CE requirement for relicensure.

Disclosure Statements:

Authors: Dr. Escobedo has no disclosures.

Dr. Lighthizer is a consultant for Aerie Pharmaceuticals and Nova Oculus and has received honoraria from Alcon, Bio-Tissue, Diopsys, MacuLogix, Nidek, Optovue, Quantel, Reichert, RevolutionEHR and Shire.

Editorial staff: Jack Persico, Rebecca Hepp, William Kekevian, Catherine Manthorp and Mark De Leon all have no relationships to disclose.

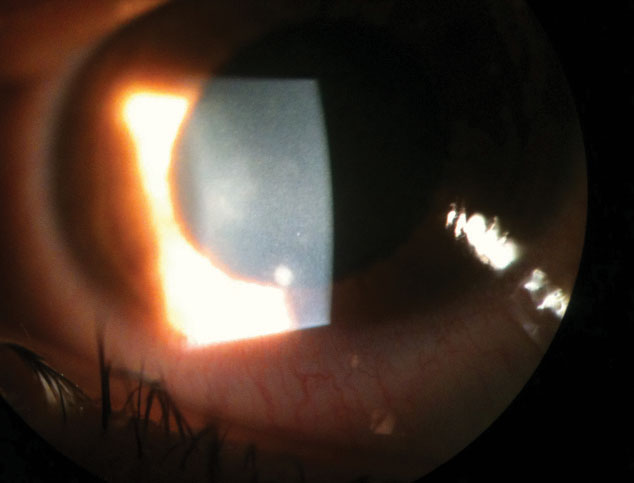

Consider this clinical encounter: a patient presents to the emergency room with a red left eye that has persisted for several days (Figure 1). The patient denies any vision changes or photophobia. Slit lamp examination reveals a severely injected temporal bulbar conjunctiva located near an area of corneal thinning and opacification. Upon questioning regarding the clinical history and events leading up to the symptoms, the patient reports minimal pain and denies both contact lens wear and any mucus discharge.

This patient has a corneal ulcer, a condition eye care providers encounter on a routine basis. Ulcers are defined as tissue loss located within the stroma or subepithelial layers of the cornea and are often accompanied by infiltrates, an influx or migration of white blood cells. The definition purposefully does not mention whether an ulcer is infectious or sterile—because it can be either. Thus, in cases such as this, clinicians should always ask, “Is this condition infectious or sterile?” The first step to answering this question is to analyze critical components such as pain, epithelial defect, anterior chamber reaction and location.

While practitioners often concern themselves with infectious etiologies, it’s imperative they be familiar with the possible causes of each and know how to differentiate between the two presentations, as the treatments can be drastically different. This discussion zeroes in on the different types of non-infectious ulcers and reviews their etiologies, presentations and treatments.

|

| Fig. 1. Peripheral corneal ulceration with adjacent bulbar conjunctival injection. |

No Bugs Here

Cases with a non-infectious etiology tend to have variable presentations but often share a few similar components such as location and progression, keeping in mind that any systemic condition contributing to the ulceration is being controlled. Most sterile ulcerations involve infiltration or thinning of the cornea near the limbus and have an associated injection of either the bulbar conjunctiva or sclera.

This peripheral location is a critical factor in determining an infectious vs. sterile etiology, with a peripheral location strongly pointing more toward a sterile cause. Pain, mucopurulent discharge and anterior chamber reaction all tend to be much less prominent, or even non-existent, compared with infectious etiologies. In addition, because these ulcerations are commonly associated with other conditions, such as irregular eyelid anatomy, malfunction of the nervous system and many systemic conditions, progression and management can become complex. Here is a look at many common ocular sterile etiologies and how to treat them:

Marginal keratitis. This is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction to bacterial antigens in the presence of Staphylococcal blepharitis. Patients will commonly present with red, irritated eyelid margins that are thickened, with prominent blood vessels.1 Anterior segment examination can also reveal peripheral corneal infiltrates that can be unilateral or bilateral and are found near the limbal area. These infiltrates are often accompanied by sectoral conjunctival injection.

In cases where the etiology is indeterminate, it is helpful to investigate whether the patient has ever been diagnosed with rosacea. These patients commonly present with poor eyelid hygiene along with associated facial symptoms such as facial flushing and papular skin lesions.1

Treatment for these patients begins with lid scrubs and warm compresses to improve lid margin presentation. Antibiotic ointment, such as erythromycin, can also help to reduce the over-proliferation of eyelid bacteria. Patients who present with corneal involvement should be prescribed a topical antibiotic, and possibly a topical steroid, to reduce inflammation and irritation. Due to the chronic nature of rosacea, it is likely these patients will experience recurrent episodes of marginal keratitis. In these cases, clinicians should consider prescribing oral antibiotics, such as doxycycline, to help counteract damaging chronic inflammation. They should follow up in two to seven days to manage lid hygiene and corneal presentation for mild to moderate cases.

Clinicians should also manage intraocular pressure in patients who are prescribed topical steroids. Severe and chronic cases, especially those managed with oral antibiotics, should be followed more closely with a tapering over the course of three to six months, depending on presentation and the patient’s overall systemic health.1

Contact lens-associated ulcer. A similar presentation is that of a contact lens peripheral sterile infiltrate, a hypersensitivity reaction to bacterial antigens or chemicals involved in lens care (Figure 2).2 Infiltrates can also occur secondary to functional changes in the corneal tissue, such as a reduction in epithelial mitosis and a decrease in the density of terminal nerve endings due to contact lens wear.3 Like marginal keratitis, a contact lens-associated ulcer presents with peripheral corneal infiltrates commonly accompanied by sectoral conjunctival injection and minimal to no epithelial defects. If epithelial defects are present, they tend to be much smaller than the underlying infiltrate.

With the exception of oral antibiotics, treatment is similar to that of marginal keratitis. While the patient is being treated, contact lens wear should be discontinued, and switching to a daily disposable lens should be considered following resolution of the acute event. In the event sterility is questionable and contact lens wear is a contributor, the recommended approach for treatment is a broad-spectrum antibiotic to cover for any possible infectious pathogens.

|

| Fig. 2. This peripheral infiltrate is due to contact lens wear. |

Neurotrophic keratopathy. This is a rare degenerative corneal disease caused by impairment of trigeminal innervation, leading to corneal epithelial breakdown, impairment of healing and development of corneal ulceration, melting and perforation. The hallmark of neurotrophic keratitis is decreased corneal sensitivity, which can result from acquired damage to the trigeminal ganglion, stroke, aneurysm or tumor.4 Systemic diseases and congenital disorders, including diabetes, multiple sclerosis and Goldenhar syndrome, are also associated with neurotrophic keratopathy.5 Ocular conditions that can lead to a decrease in corneal sensitivity include herpes simplex, herpes zoster keratitis, chronic use of eye drops such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and anesthetics, chemical burns and refractive corneal surgeries.

The clinical presentation of neurotrophic keratitis is a persistent, non-healing epithelial defect with heaped-up edges that stains readily with fluorescein. If progression occurs, stromal haze, scarring and thinning can present and lead to corneal melting.

Due to the decrease in corneal sensitivity, patients often present with few symptoms. The management of neurotrophic keratitis can be complex, depending on the severity. In any case, heavy lubrication with artificial tears is highly recommended to improve the health of the corneal surface.

Topical steroid and nonsteroidal drops should be avoided due to the inhibition of stromal healing and increased risk of corneal melting.5 In severe cases with stromal involvement, collagenase inhibitors, such as tetracyclines and acetylcysteine, should be considered.

Other possible treatments include therapeutic corneal or scleral contact lenses with consideration of autologous serum and amniotic membranes to promote corneal healing.4

Exposure keratopathy. This is a result of an unhealthy corneal surface and irregular anatomical function, such as ocular surface dryness secondary to abnormal eyelid blinking or incomplete eyelid closure.2,5 Possible causes of exposure keratopathy include Bell’s palsy or a facial nerve palsy secondary to surgery of an acoustic neuroma or parotid tumor, reduced muscle tone associated with Parkinsonism and severe proptosis due to thyroid eye disease or orbital tumor. Abnormal anatomical structural causes can include ectropion, nocturnal lagophthalmos and tight facial skin following blepharoplasty or eyelid excision of tumors.2

With similar etiologies, neurotrophic keratitis and exposure keratopathy may be difficult to distinguish without a clear history. However, clinical presentation and patient symptoms are two key components that help differentiate the conditions. Unlike neurotrophic keratitis, patients that present with exposure keratopathy will be symptomatic of severe dryness, ocular injection and possibly pain depending on the chronicity and severity of the condition. Punctate epithelial defects will be noted in the inferior third of the corneal surface and, in severe cases, pannus, sterile ulceration or infectious keratitis may occur. Under rare circumstances, stromal melting can eventually lead to perforation.1

Treatment for these patients is based on the severity of the condition and expected timeline of recovery.5 In mild to moderate cases, causes of exposure are commonly reversible, and treatment can involve heavy lubrication during the day and ointment application at night. Taping of the eyelids or the use of a patch can be alternatives to ointment with a sterile presentation. Other viable options for these cases include bandage silicone hydrogel lenses, scleral contact lenses and temporary tarsorrhaphy. Severe and chronic cases that lead to permanent exposure can be treated with a permanent tarsorrhaphy, gold weights or conjunctival flaps. When managing exposure keratopathy in patients with severe proptosis, orbital decompression is also an option.

The Other Side of the Coin

Infectious corneal ulcers, better known as infectious keratitis, are those that become infiltrated by either a bacterial or non-bacterial pathogen (i.e., fungus, protozoan or herpes virus). The most ubiquitous of all pathogens is Pseudomonas aeruginosa, covering 60% of contact lens-related keratitis.5 Other common pathogens include Moraxella, S. pneumonia, S. epidermidis, Serratia and Klebsiella. Common symptoms of infectious keratitis include pain, photophobia, blurred vision and mucopurulent or purulent discharge.5 Anterior segment signs tend to present in a certain chronological order that can help determine causation. Early stages include an epithelial defect with a large infiltrate that is often accompanied by stromal edema and anterior uveitis. Severe, chronic cases can result in rapid progression of infiltration with an enlarging hypopyon.5 Early treatment is critical for these patients to prevent aggressive inflammation and possible perforation. First-line therapy usually consists of a broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone; however, advanced central corneal ulcers suspicious of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus will require either fortified tobramycin or vancomycin. Lastly, depending on the pathogen and severity, some cases may need surgical intervention or hospital admission. |

More than Meets the Eye

When dealing with a suspected sterile corneal ulcer, clinicians should always consider systemic conditions, such as these, as a potential cause:

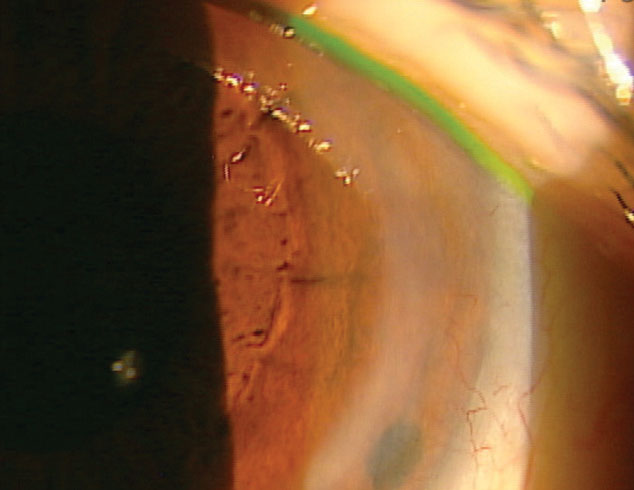

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK). This is a severe peripheral corneal infiltration, ulceration or thinning that cannot be explained by evident ocular disease. These cases should be highly suspicious for associated collagen vascular diseases, which account for 50% of PUK cases.6 Rheumatoid arthritis, which can lead to some of the worst presentations of sterile corneal ulceration, is the most common associated systemic disorder, presenting in 34% of noninfectious cases, with 30% of patients having bilateral findings (Figure 3).6Wegener’s granulomatosis is the second most common associated systemic condition and almost always presents with scleritis.6 Less common systemic conditions that can lead to PUK include relapsing polychondritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.

PUK presents clinically with a crescent ulceration and stromal infiltration located at the limbus and is commonly associated with episcleritis or scleritis. Chronic cases of PUK can spread centrally on the cornea and extend into the sclera. The depth of peripheral corneal thinning is variable, with severe cases leading to perforation, with or without trauma.6

The goal of treatment for these patients is to reduce ocular inflammation, promote epithelial healing and minimize stromal loss. Unfortunately, unless the associated systemic disease is appropriately managed, treatment results are not promising.6 In Wegener’s, comanagement with a rheumatologist is indicated to manage a potentially life-threatening systemic vasculitis.

Treatment for PUK can be further broken down into local, systemic and surgical options. Solely local treatments are reserved for the few patients without an underlying systemic disease who have an associated marginal or peripheral ulcerative keratitis. These patients should be given topical antibiotics along with education on the importance of eyelid hygiene. Topical corticosteroids can also be prescribed and tapered based on clinical response.6

Systemic corticosteroids are the traditional first-line therapy for acute PUK and are often accompanied by an immunosuppressant due to their inability to inhibit disease progression or overcome the systemic autoimmune disease.6

Surgical treatment options include the use of a tissue adhesive, bandage contact lens, lamellar graft, tectonic corneal grafting and amniotic membrane transplant.6

Despite the improvements that have been made in cytotoxic therapy, studies show ulcerative keratitis has the highest likelihood of a regraft.6 Overall, controlling ocular inflammation is critical in these patients, but making sure the underlying systemic disease is controlled can be life saving. Due to potential side effects from the use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, it is important to follow up with these patients regularly and stay up to date with lab testing.6

Shield ulcer. This is a sterile corneal ulceration found in patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC). The condition mainly affects young boys in their first decade of life, and the sequelae may result in permanent visual impairment.7 These patients have a family history of atopic diseases in 49% of cases and a personal medical history of other atopic conditions such as asthma (26.7%), rhinitis (20%) and eczema (9.7%).7

Clinical presentation of a shield ulcer is commonly associated with palpebral VKC, which primarily involves the upper tarsal conjunctiva and is characterized by diffuse papillae that eventually progresses into giant papillae, greater than 1mm in size, with mucus discharge between the papillae. The close apposition of the superior conjunctival papillae to the corneal epithelium results in corneal surface disease, including shield ulcers and Trantas’ dots, an aggregate of epithelial cells and eosinophils at the limbus. VKC generally subsides with the onset of puberty, but some therapeutic measures may be required beyond this age to control the course of the disease.7

Treatment options begin with a prophylactic approach for seasonal atopic conditions and extend into surgical procedures for more devastating cases involving sterile ulceration. Prophylactic measures include patients becoming aware of their vulnerability, commonly by an allergy specialist, and avoiding the triggering allergen to reduce the chances of inflammation. Common triggers include sun, dust, wind and other general environmental factors.7

In these cases, cold compresses and proper lid hygiene are recommended to help with symptoms of irritation and signs of possible Staphylococcal hypersensitivity, respectively. Topical antihistamines are commonly used in acute episodes but are less effective when used alone during chronic disease. Mast-cell stabilizers are frequently used in combination with NSAIDs for the long-term.5 Topical steroids are considered when a quick tapering is expected and are often prescribed in heavy doses, with the possibility of a supratarsal steroid injection in cases with severe palpebral disease. Immune modulators, such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus, are viable options for high-risk steroid patients.5

Surgical treatments such as superficial keratectomy are considered for the removal of plaques or the debridement of a corneal ulcer. Furthermore, patients being treated with topical steroids should be strictly monitored due to the incidence of glaucoma in VKC patients (2%). Once the acute phase runs its course, steroids should be discontinued and replaced with alternatives such as mast-cell stabilizers, antihistamines or NSAIDs.7

Patients with VKC generally have spontaneous resolution of the disease after puberty without any further symptoms or visual complications. However, corneal ulcers, which are reported to develop in 9.7% of patients, can produce a permanent visual impairment.7

|

| Fig. 3. Stable PUK in a long-standing RA patient. |

Mooren’s ulcer. Unfortunately, clinicians may sometimes encounter a case in which etiology is controversial or indeterminate, as is often the case with this presentation. Mooren’s ulcer is a rare, idiopathic disease thought to have an autoimmune component and possibly be associated with environmental factors of corneal insult such as surgery, trauma or infection. The disease may present itself unilaterally or bilaterally. It is rare in the northern hemisphere but common in the southern hemisphere and other geographical locations such as China, Africa and India.8

Clinically, Mooren’s ulcer is characterized by a progressive circumferential peripheral stromal ulceration, which has the potential to spread centrally. There are two types of presentations, with the first being unilateral and more benign. It predominantly affects the elderly and responds well to treatment. The second type is more aggressive, predominantly affects young males, has a bilateral presentation and does not respond well to medical therapy. Vascularization of the stromal bed can also be present in terminal stages of the condition and eventually leads to scarring as the cornea begins to heal.5 Mooren’s ulcer is a diagnosis of exclusion and is often diagnosed once other etiologies, such as PUK, have been eliminated.

Topical treatments for Mooren’s ulcer include combinations of steroids, antibiotics, artificial tears and, in some cases, collagenase inhibitors such as acetylcysteine. Unfortunately, for those within the second group, visual prognosis is poor, even with treatment.

Systemic therapy includes immunosuppressants and collagenase inhibitors such as doxycycline. Surgical options include conjunctival resection and lamellar keratectomy, as well as penetrating keratoplasty. Post-surgical intervention includes vision rehabilitation once inflammation has settled.5 During follow-up exams, these patients should be monitored for secondary infections. Eye care providers should comanage with the patient’s primary care physician to make sure any underlying systemic conditions are being addressed.

Pain, photophobia and discharge are common signs and symptoms a patient mentions when they present with a corneal ulcer. While infectious causes are often the focus of discussion, sterile ulcers come with their own concerns worth understanding—as the right treatment depends on it. A widely agreed upon treatment approach with an unknown etiology is a broad-spectrum antibiotic, such as a fluoroquinolone, to cover for severe pathogens such as Pseudomonas. However, treatment must be far more tailored to ensure successful resolution.

Once an infectious etiology has been eliminated due to a lack of common findings such as mucus discharge, anterior chamber reaction and contact lens wear, clinicians should then consider the possibility of an associated systemic condition and other ocular surface diseases, as both are common with a sterile ulcer. Knowing the etiologies of sterile ulcers will guide the clinician through potential treatment options, both systemic and topical, to best care for each and every patient.

Dr. Escobedo is a graduate of Midwestern University, Arizona College of Optometry and is the current Cornea and Contact Lens Resident at Northeastern State University (NSU) Oklahoma College of Optometry.

Dr. Lighthizer is the assistant dean for clinical care services, director of continuing education and chief of both the specialty care clinic and the electrodiagnostics clinic at NSU Oklahoma College of Optometry.

1. Bagheri N, Wajda B, Calvo C, Durrani A. The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2016. 2. Rapuano CJ. The Wills Eye Institute: Cornea. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2012:30-231. 3. Ammer R. Effect of contact lens wear on cornea. J Ophthalmol. 2016. 32(4):216-20. 4. Sacchetti M, Lambiase A. Diagnosis and management of neurotrophic keratitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:571. 5. Kanski JJ, Bowling B. Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systemic Approach. 7th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2012. 6. Yagci A. Update on peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:747. 7. Bonini S, Coassin M, Aronni S, Lambiase A. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Eye. 2004;18(4): 345. 8. Yang L, Xiao J, Wang J, Zhang H. Clinical characteristics and risk factors of recurrent Mooren’s ulcer. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:8978527. |