|

But adults aren’t the only ones in need of treatment. A retrospective study to determine the incidence and presentation of pediatric keratoconus (younger than 14) found that over a five-year period, 541 of 2,972 patients were diagnosed with keratoconus—an incidence of 0.53%, representing 2.96% of all cases diagnosed during that time.1 In comparison, the incidence in the adult population is 3.78%.1

Because studies evaluating the efficacy of CXL have focused on adults, the incidence and severity of keratoconus in children is poorly understood, as is the potential role for CXL in the pediatric population.

Pediatric Challenges

Treating children presents a number of unique challenges. Most management strategies successful with adults, such as specialty contact lenses, are less so with children, given complications such as difficulty with wear and care compliance and poor outcomes with corneal transplantation.2,3 Keratoconus in children is often associated with vernal keratoconjunctivitis and eye rubbing, which can lead to hydrops, so care must be taken to quell the surface inflammation with topical anti-allergy and steroid drops.4

Additionally, keratoconus in children tends to be more severe at initial presentation and progresses more quickly than in newly diagnosed adult patients.5 A retrospective study of 49 patients younger than 15 and 167 older than 27 with keratoconus at initial presentation found the disease was more severe at diagnosis in subjects in the first group: 27.8% were already at stage 4 using Krumeich’s classification, as compared with 7.8% of adult subjects.5 Stage 4 includes non-measurable refraction; mean central keratometry readings >55 diopters; central corneal scarring and a minimum corneal thickness of 200μm. The younger subjects also had more advanced slit lamp signs and keratometry readings.5

|

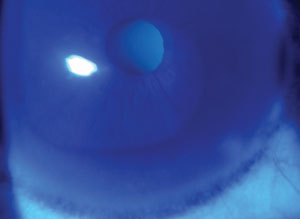

| A Fleischer ring, as seen in some keratoconus patients. |

CXL in Kids: The Literature

Given the difficulties in fitting the pediatric population with contact lenses and the greater propensity for full thickness corneal graft rejection, CXL could be the answer, as preliminary studies indicate it stabilizes the disease process and reduces the need for keratoplasties. So far, three studies have evaluated the efficacy of CXL—with a standard epi-off treatment—and the progression of keratoconus in the pediatric population. Patients were pretreated with topical anesthesia and removal of the corneal epithelium, followed by a soak of 0.1% riboflavin/20% dextran solution (varied from 10 to 30 minutes) and then 30 minutes of UVA irradiation (six times for five minutes each), with instillation of riboflavin/dextran every five minutes. Post-procedure, antibiotic and cycloplegic drops were instilled, along with a bandage contact lens. Some children required general anesthesia, while others required only topical.6-8

One study evaluated patients age 10 to 18, divided into two groups by corneal thickness: less than 450μm and greater than 450μm.6 At 36 months post-CXL treatment, no adverse events were reported and both groups showed an improvement in uncorrected Snellen visual acuity (VA), topography and coma. There was a faster functional response in patients with thinner corneas.

Another study evaluated the refractive, topographic, aberrometric and tomographic results in patients ages nine to 18 for up to two years.7 There was a slow but continuous improvement of most of the indices up to 24 months after surgery, with no adverse events noted.

Finally, a study evaluating patients age nine to 19 for progression of keratoconus and the efficacy of CXL up to three years postoperatively found 88% exhibited progression (an increase in the maximum keratometry of at least 1.00D over a one-year period).7 The researchers analyzed maximum keratometry values, corrected distance VA, corneal thickness and the keratoconic index. They found the maximum keratometry value was reduced by three months and remained for up to 24 months. However, at 24 months, it began to show progression, suggesting pediatric corneas do not allow for long-term improvement, although the best-corrected distance VA continued to be better than pre-CXL.8

One study performed transepithelial (epi-on) CXL on 13 eyes in patients ages eight to 18.9 While the procedure was safe, well tolerated and the corrected distance visual acuity was improved at 18 months of follow-up, it did not halt the progression of keratoconus as seen with the standard epi-off treatment.9

This research suggests keratoconus in pediatric patients is more severe and progresses more quickly than in adults, and standard CXL is safe and effective, although perhaps more transient, in patients younger than 18.

More studies with longer follow up are needed, but it appears CXL can be seriously considered in our treatment of keratoconus for patients as young as 14.

1. el-Khory S, Abdelmassih Y, Hamade A, et al. Pediatric keratoconus in a tertiary referral center: incidence, presentation, risk factors and treatment. J refract Surg. 2016;32(8):534-41.

2. Vanathi M, Panda V, Vengayil S, et al. Pediatric keratoplasty. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:245-71.

3. Lowe MT, Keane MC, Coster DJ, Williams KA. The outcome of corneal transplantation in infants, children and adolescents. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:492-7.

4. Rehaney U, Reumelt S. Corneal hydrops associated with vernal keratoconjunctivitis as a presenting sign of keratoconus in children. Ophthalmology. 1995:1021(12):2046-9.

5. Leoni-Mesplie S, Moortemousque B, Touboul D, et al. Scalability and severity of keratoconus in children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154:56-62.

6. Caporossi A, Mazzotta C, Baiocchi S, et al. Riboflavin-UVA-induced corneal collagen crosslinking in pediatric patients. Cornea. 2012;31(3):227-31.

7. Vinciguerra P, Albé E, Frueh BE, et al. Two-year corneal cross-linking results in patients younger than 18 years with documented progressive keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012 Sep;154(3):520-6.

8. Chatzis N, Hafezi F. Progression of keratoconus and efficacy of pediatric corneal collagen crosslinking. J Refract Surg. 2012 Nov;28(11):753-8.

9. Buzzonetti L, Petrocelli G. Transepithelial corneal cross-linking in pediatric patients: early results. J Refract Surg. 2012 Nov;28(11):763-7.