Contact lenses are some of the smallest and least visible devices for correction of refractive error. Considered medical devices, they can be worn for therapeutic reasons; however, other reasons for wearing contact lenses exist, such as for cosmetic purposes.1 Contact lenses are an important part of the ophthalmologist practice, with the demand for them increasing day-by-day; indeed, millions worldwide currently wear them.2 Therefore, it is also important to take precautions and educate people when prescribing and fitting these lenses.3

History

A 47-year-old female patient presented to the clinic with a red left eye that had been present for the past seven days. This was accompanied by a foreign body sensation and watering, but no discharge. She noted the presence of localized swelling on her left upper eyelid with a nodular-looking lesion. She was treated for lid cyst with chloramphenicol ointment by the general practitioner. Since then, however, the condition had not improved and so she decided to consult an eye specialist. The right eye appeared to be without complaint or redness. The patient was a gas permeable contact lens wearer with her last wear time occurring eight days ago.

| |

| Fig. 1. The patient presented with a firm nodule near the center of the eyelid of unknown origin. | |

| |

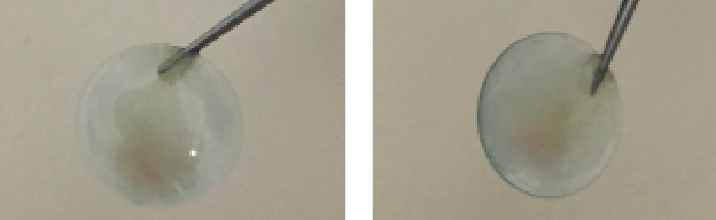

| Fig. 2. Everting the patient’s left eyelid revealed the presence of a GP contact lens. |

The patient exhibited no other ocular history, and her family ocular history was negative for ocular problems. She wasn’t taking any systemic medications at the time of admittance and her best-corrected visual acuities were 20/30 OD and 20/25 OS. Pupils were round and reactive to light, with no relative afferent pupillary defect in either eye. Extraocular movements were full OU. A slit lamp examination demonstrated that the left eyelid was normal. Additionally, the left conjunctiva was white and quiet; the cornea, iris and lens were clear; and the anterior chamber was deep and quiet. Regarding the right eye, a 1.0mm by 0.7mm firm nodule on the center of the upper left eyelid was visible, with no periorbital erythema or edema or skin breaks (Figure 1). The right conjunctiva displayed hyperemic traits and the cornea was characterized by a few punctate epithelial erosions. The anterior chamber was deep and quiet, the iris was round and regular and the lens was clear.

Upon inversion of the left upper eyelid, a circular foreign body was made visible, surrounded by the tarsal conjunctiva (Figure 2). Attempts to shift it with a cotton bud were unsuccessful and subsequently, oxybuprocaine eye drops were instilled. The object—a contact lens—was removed using typing forceps. A yellow pus discharge on the contact lens was observed immediately (Figure 3). Both the lens and the discharge was sent for culture and sensitivity. The patient reported increased comfort, and was sent home with topical ofloxacin eye drops and the expectation that she would return in three days.

Culture results indicated the presence of Staphylococcus aureus, which proved sensitive to the ofloxacin. The patient reported no issue on follow-up, and was asked to continue the drop regimen for another week. A two-week follow-up appointment revealed everything had healed well.

Discussion

Gas permeable contact lenses (GPs) are made of a complex polymer that includes silicone, PMMA and others. These lenses permit excellent perfusion of oxygen and are used to improve vision by correcting refractive errors.4 They work by focusing light so that it enters the eye with the proper power for clear vision.5 GP lenses have the main advantage of being durable with longer lifespans as compared with soft contact lenses. Modern GP lenses require a relatively short adaptation time as compared with older hard lenses, but patients still need some time to get used to them. Additionally, the size of the lenses is beneficial as it provides for easy insertion and the flexibility to allow them to move freely on the eye with each blink; however, their small size can be disadvantageous as the lens may move from its position during daily activities or sports and be lost. This also increases risk for debris to become trapped underneath the lens.

This patient in particular dislodged her contact lens from its original position to where it sat on the palpebral or tarsal conjunctiva. The conjunctiva then began to fold over the lens. The patient reported she was aware of the time she placed the contact lens on the eye, but that she was not aware if and when she had lost the lens.2

| |

| Fig. 3. Lens removal led to the discovery of discharge. |

Contact lens complications can vary from mild irritation to sight-threatening issues, with resulting problems leading to disturbances of the eyelids and ocular surfaces that can result in long-term changes and a reduction in contact lens tolerance. In this case, the extended wear of a GP lens led to complications that likely began as a result of abnormal blinking of the eyelid, ptosis due to a reduction of the palpebral slit and meibomian gland dysfunction.6

Other complications that might present may relate to the tear film and result in dry eye due to the lack of lipids. This can lead to papillary conjunctivitis, which is intensified by the mechanical irritation of the conjunctiva. Additionally, the presence of hypoxia below the lid, accompanied with an immunological reaction may also induce corneal changes like microcysts and striae such that GPs may not allow enough transmission of oxygen for successful long-term extended wear. Wear of the lens may also result in disruption of the corneal epithelium, corneal erosion and keratitis if not treated promptly. Corneal edema and corneal ulcers are two sight-threatening complications that can occur with contact lens wear.2,7,8

Regardless of the brand of contact lenses, however, their use requires accompanying care to prevent damage and avoid sight-threatening complications. The majority of contact lens complications are caused by careless handling and overwear of lenses. As such, patient education is key, as is early identification of the above mentioned conditions so that necessary medical help can be sought.

Dr. Tallouzi is a surgical practitioner working at Birmingham and Midland eye Hospital. He specializes in treatment of ocular surface and inflammatory eye diseases and was awarded the NIHR Clinical Research Training Fellowship in 2015. He is currently working on his PhD at the University of Birmingham.

1. Farandos M, Yetisen K, Monteiro J, et al. Contact lens sensors in ocular diagnostics. Advanced Healthcare Materials. 2015 Apr 22;4(6):792-810.

2. Lemp M and Bielory L. Contact lenses and associated anterior segment disorders: dry eye disease, blepharitis and allergy. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008 Feb;28(1):105-17. vi-vii.

3. Dart JK, Saw VP, Kilvington S. Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis and treatment update 2009. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008 Oct:148(4):487-499.e2.

4. Denniston A and Murray P. Oxford Handbook of Ophthalmology. 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009.

5. Benjamin L. Training in Ophthalmology: The Essential Curriculum. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009.

6. Beljan J, Beljan K and Beljan Z. Complications caused by contact lens wearing. Coli Antropol. 2013 Apr;37 Suppl 1:179-87.

7. Compan V, Andrio A, Lopez-Alemany A, et al. Oxygen permeability of hydrogel contact lenses with organosilicon moieties. Biomaterials. 2002 Jul;23(13)2767-72.

8. Ehler J, Shah C, Fenton G, Hoskins E. The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. 4th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.