|

A patient presents to your office requiring a topical antibiotic for a corneal ulcer. Another patient comes in with bilateral uveitis and needs a topical steroid. A third patient complains of debilitating ocular allergies. What do these patients all have in common? They are all in their first trimester of pregnancy. So, keeping this in mind, what criteria do you use to guide your selection of medications?

Many practitioners have relied heavily if not exclusively on the longstanding FDA pregnancy labeling system for prescription medications to make this call. First instituted in 1979 in response to the thalidomide disaster of the early 1960s, in which thousands of babies were born with severely deformed extremities after the drug was marketed as a preventative for morning sickness, the system is comprised of five categories: drugs are labeled A, B, C, D or X based on a series of predetermined FDA risk factors, with A being considered the safest category. Each category was defined by the absence or presence of data in animals and/or humans and the study results.1 Additionally, categories D and X included information about the drug’s benefits for the mother, along with potential fetal risks. The FDA also determined safety data could be omitted for drugs that are not systemically absorbed as well as for drugs without sufficient studies to demonstrate risk.2

In the years since the labeling system’s institution, however, many shortcomings have been identified; this month’s column will provide a brief overview of the impetus for change and what the change involves.

Making the Change

There are approximately 6.5 million pregnancies annually in the United States, with an estimated yearly pregnancy rate among women ages 15 to 44 at 11%.3 In a retrospective study on the prevalence of prescription drug use among pregnant women, researchers found that approximately 64% of women are prescribed a drug during pregnancy; of those receiving a prescription medication, 50% of the drugs came from category B, 37.8% from category C, 4.8% from category D and 4.6% from category X.2 Other data has suggested that as many as 80% of women receive prescription medications during pregnancy, with an average of 3.1 prescriptions per person.2 Approximately 66% of all prescription medications were labeled as category C.2

|

The FDA realized as early as 1997 there were problems with the 1979 labeling, but it has taken almost two decades for change to occur. Known problems include oversimplification of drug use during pregnancy, the incorrect assumption that all drugs in a particular category share the same risks, and that supporting test data is not clearly distinguished as to whether it is from animals or humans.1,2,5

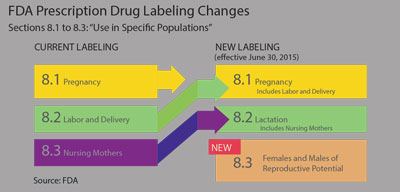

To overcome these concerns, the FDA proposed the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR) in 2008 and, after minor changes, the final PLLR was adopted effective June 30, 2015. The most striking difference between this and the old labeling system was the elimination of the pregnancy letter categories. In addition, the content and format for the labeling of prescription drugs and biological products has been reorganized with changes in titles and headings:

- Section 8 on every package insert now addresses prescription drug use in specific populations.

- Section 8.1 will now be called “Pregnancy” and will now include a section on labor and delivery. Other subcategories will include “Pregnancy Exposure Registry,” with directions to include contact information for enrollment if applicable; “Risk Summary” and “Clinical Considerations and Data.” The latter two sections will be required to clearly delineate if the findings were from human, animal or pharmacology studies.

- Section 8.2 will now be called “Lactation, including Nursing Mothers,” which was formerly Section 8.3. This section will also contain subsections on risk and clinical considerations and data, with similar requirements to Section 8.1.

- The revised Section 8.3 is now labeled “Females and Males of Reproductive Potential.” This section will address whether pregnancy testing and/or contraception are recommended in conjunction with the drug therapy. Also addressed in this section will be any human or animal data that suggests drug-related infertility.6-8

Prescription drugs submitted to the FDA for approval after June 30, 2015 will immediately use this new formatting. Labeling for over-the-counter medicines, however, will not be affected by the PLLR and thus will not change. Drug applications approved after June 30, 2001 will have three years to make labeling changes. Drugs approved prior to June 30, 2001 will not be required to reformat the labeling to be consistent with the new content, but will be required to remove the pregnancy risk category (i.e., A, B, C, D or X) within three years.2,7

Overall, the PLLR is expected to provide the practitioner with a better understanding of the risks associated with prescription medications during pregnancy and lactation. It will equip the clinician with better information including a summary of the risks of using a drug, data supporting that summary and relevant information which will help when selecting medications and allow for better communication to the patient about the risks/benefits to the patient and the fetus. Additionally, more comprehensive information will be available as well for patients of reproductive potential who may be contemplating pregnancy. Though simplicity has been eliminated, our pregnant patients who need prescription drugs will still benefit from these significant changes.

1. Feibus, KB. FDA’s proposed rule for pregnancy and lactation labeling: improving maternal child health through well-informed medicine use. J Med Toxicol. 2008;4(4):284-288.2. Ramoz LL, Patel-Shori NM. Recent changes in pregnancy and lactation labeling: retirement of risk categories. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(4):389-395.

3. Ventura SJ, Curtin SC, Abma, JC, Henshaw SK. Estimated pregnancy rates and rates of pregnancy outcomes for the united states, 1990-2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2012;60:1-12.

4. Andrade SE, Gurwitz JH, Davis RL, Chan KA, et al. Prescription drug use in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(2):398-407.

5. Sannerstedt R, Lundborg P, Danielsson BR, Kihlstrom I, et al. Drugs during pregnancy: an issue of risk classification and information to prescribers. Drug Saf. 1996;14(2):69-77.

6. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Final Rule. Available at: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/Labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed June 15, 2015.

7. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Questions and Answers on the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule. Available at: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/Labeling/ucm093311.htm. Accessed June 15, 2015.

8. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Content and Format of Labeling for Human Prescription Drugs and Biological Products: requirements for pregnancy and lactation labeling. Available at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2014-28241.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2015.