Several options give presbyopic patients the opportunity to reverse the clock and enjoy improved vision and quality of life. Multifocal contact lenses, being one of these choices, provide patients good vision at all distances and freedom from reading glasses. There are many different optical designs and a few contact lens modalities that deliver multifocal optics, such as soft lenses, gas permeable lenses and hybrid lenses, but what about scleral lenses? Can we include them on this list?

Scleral lenses have seen tremendous growth over the past 10 years and are no longer a niche product. Traditionally, scleral lenses have been used in the non-surgical visual rehabilitation of irregular corneal conditions and as an adjunct therapeutic management strategy for ocular surface disease. Today, scleral lenses are also used to manage refractive error in patients with normal corneas.

Though many patients are thrilled with the distance vision and comfort these lenses provide, presbyopic patients want great vision at all distances while remaining spectacle-free. The following article will go into detail on how to check off this box for patients when presbyopia presents because no matter the indication for scleral lens wear, we know all patients eventually develop the condition.

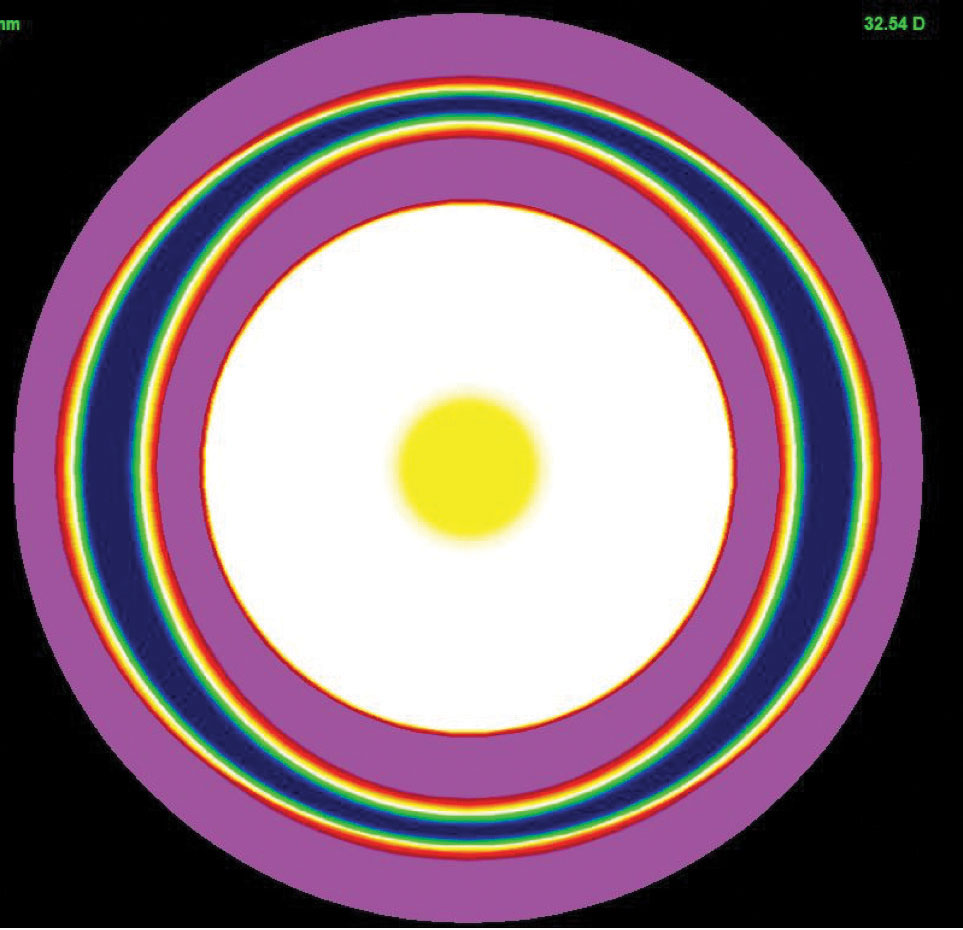

|

| Simulated center-near multifocal design image from focal points. |

Goodbye Glasses

The search for spectacle-free near vision is nothing new. Patients have long searched for options to make this a reality.

One method, monovision, has been around for decades. By correcting one eye for distance and the other for near, monovision patients who are able to tolerate it can complete most of their daily activities without additional spectacle correction. This is a well-established strategy for presbyopic scleral lens users. Monovision drawbacks include loss of binocularity and depth perception. Some patients can not adapt to monovision due to the optical disparity.

Another option is adding front surface asphericity. Though not a true multifocal design, this small change to the optics may be adequate enough to improve near vision in early presbyopes.

The last option is multifocal optics. A scleral lens with multifocal optics was rare 10 years ago, but now nearly every lab offers at least one option.

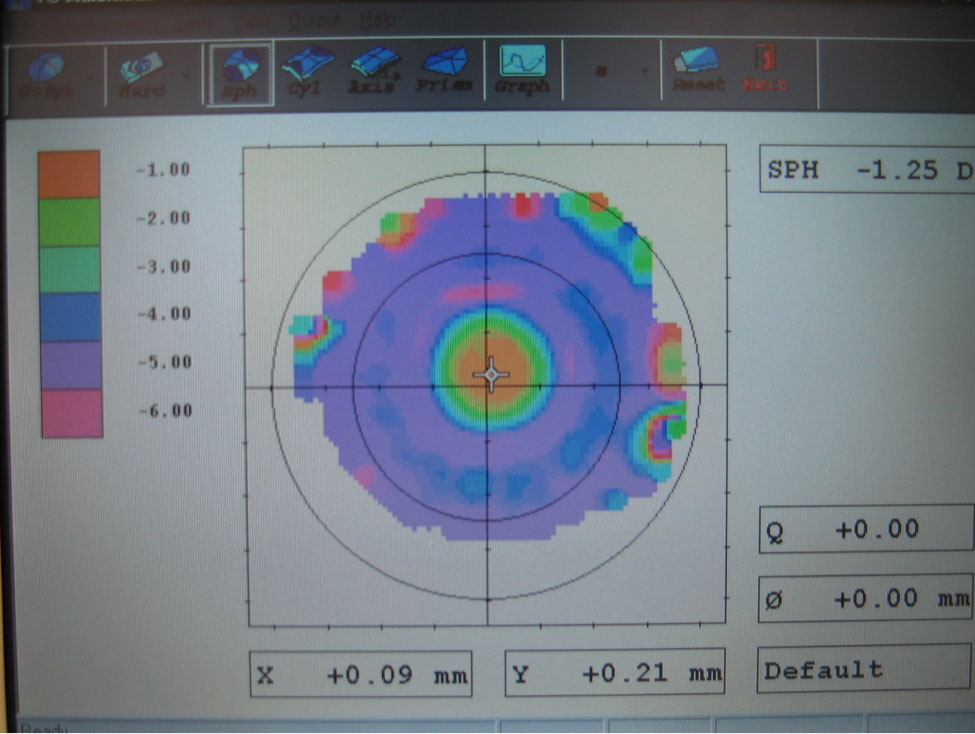

|

| Optical metrology of a center-near multifocal design. |

It’s All in the Optics

Unlike translating segmented bifocal and progressive corneal gas permeable lenses, scleral lenses do not translate on the eye. Compared with other contact lenses, scleral lenses have minimal movement and are very stable. Due to their customizable nature of matching the haptic or peripheral curves to the scleral geometry, these lenses tend not to rotate. In this sense, the lens is generally static, and, as such, simultaneous vision multifocal designs are necessary. The vast majority of multifocal optics are center-near designs. However, some labs offer center-distance designs.

Scleral lenses with multifocal optics exist in several different designs. Multifocal optics come with a gradual increase in add, allowing for more function at mid-range and near, whereas, bifocal optics cater to distance and near. Some labs offer variable zone sizes to dial-in the multifocal performance based on a patient’s pupil size.

Multifocal optics are added to the front surface of the lens in the vast majority of designs. Some labs have limited options since astigmatism correction is also added to the front surface of the lens, forcing the practitioner to choose between toric and multifocal optics.

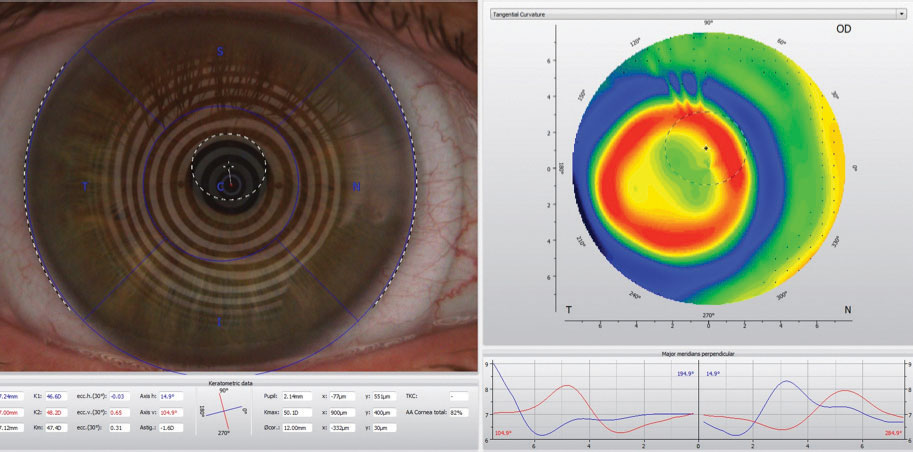

|

| On the left is what appears to be acceptable centration of the center-distance multifocal scleral lens over the cornea. This method involves placido ring projection to identify the center of the lens and then compare it to the center of the pupil. The over-topography on the right shows that the placement of the add zone is inferior temporal to the visual axis and pupil. This is due to the natural placement of the visual axis superior nasal to the center of the cornea and the slightly inferior temporal lens fit. |

Setting Candidate Expectations

With the onset of presbyopia comes other changes to the eye, such as dryness and tear layer instability. These make soft contact lenses less tolerable for many patients. In addition, the complexity and lack of historical success with correcting astigmatism and presbyopia simultaneously with anything but corneal gas permeable lenses causes many patients to use reading glasses in addition to contact lenses for their presbyopia or drop out of contact lens use altogether. Scleral lenses can fill a void in this patient population.

Multifocal scleral lenses can be used in most patients with presbyopia—but may not be the best option for all candidates—and are particularly helpful in cases of dry eye disease and regular or irregular astigmatism. Generally, patients should have less than +0.75D of residual astigmatism for the lenses to work as effectively as possible.

As with other types of multifocal contact lenses, determine best-corrected vision in each eye. If there are any complications with best-corrected vision due to things like corneal scarring, strabismus, cataracts and age-related macular degeneration, you can still prescribe multifocal scleral lenses and should educate the patient accordingly.

Just like with multifocal soft lenses, the practitioner must set realistic expectations, as vision will be functional at distance, mid-range and near but not necessarily perfect at all distances. Some patients fit with multifocal lenses feel like they are cheating if they use reading glasses. But they may be necessary in certain situations, such as threading a needle or reading a menu in a dimly lit restaurant. It’s important to understand spectacle use is normal and glasses are just another tool that can help.

|

| Mapping over a multifocal scleral lens can help with troubleshooting distance and near acuity issues. |

Finalizing Fit

The process of prescribing a multifocal scleral lens starts with a diagnostic fitting. A profilometer can help understand the scleral shape. Once the lens is placed on the eye, perform a spherocylindrical over-refraction. If the patient has +0.75D or more of residual astigmatism, discuss visual blur with them. Then, use a trial frame to simulate spherical equivalent correction and gauge tolerability and response.

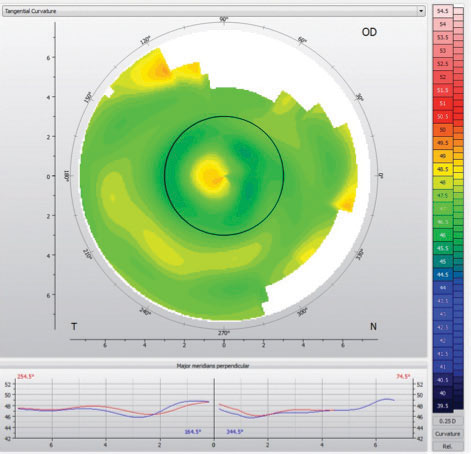

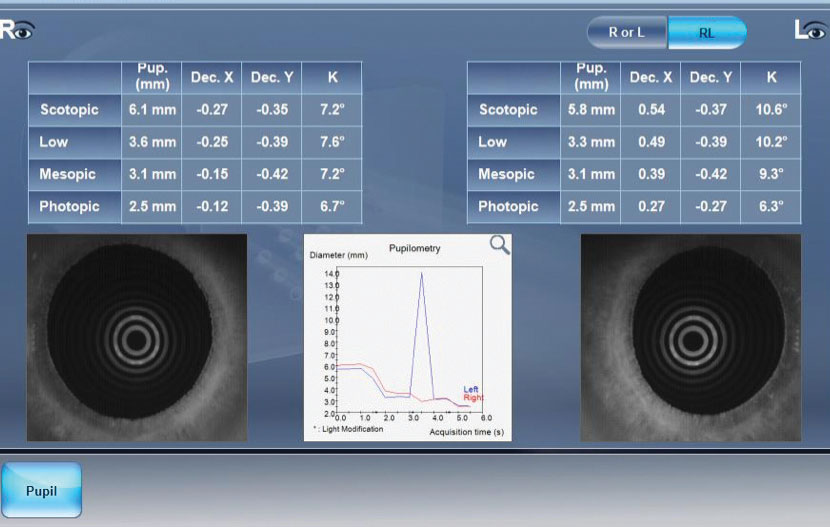

Next, determine the patient’s near add and ocular dominance. Pupil size is extremely important to take into consideration for a successful multifocal contact lens fit, and it’s no different for multifocal scleral lens fits. There are several measurement methods that can be used, including a pupil ruler, slit lamp reticule, pupilometer and topographer.

Remember to check pupil size under photopic and scotopic conditions. Keep in mind that, in some patients, starting with a low add or an aspheric multifocal design in both eyes is sufficient. Since so much of our time is spent on digital devices doing mid-range tasks, a lower-than-expected add provides adequate vision at all distances.

Then, determine the dominant eye. To determine sight dominance, instruct the patient to create a triangle and look through it at a single letter. The eye they use is the dominant eye. Sensory dominance evaluates sensitivity to blur. Place a +1.50D lens over the eye, and evaluate vision. The eye that experiences the most reduced vision is usually the dominant eye.

Once the diagnostic fitting is complete, there are two methods to fit multifocal scleral lenses. One is to finalize the fit and then the optics. Prescribe and dispense a single vision lens for distance. If the fit is acceptable and the distance prescription is accurate at follow-up, reorder the lens with the multifocal optics added. This method ensures proper fit and lens position prior to adding optics, without which the optics would not be centered on the pupil and offset optics would need to be used. The only downside is that patients are not immediately exposed to multifocal optics.

Another option is to finalize the fit and the optics at the same time. After a diagnostic fitting, order a lens with multifocal optics. If a lens is significantly different than the diagnostic lens, then the power may not be correct, making it more challenging to adjust base lens power and multifocal power simultaneously. Additionally, the lens position is dependent on the lens fitting relationship; adjustments to the fit may alter the lens position, moving the multifocal optics and creating variable optics from lens to lens.

|

| Pupillometry derived from topography. |

Off Balance

Lens decentration plays a significant role in the success or failure of multifocal scleral lenses. In general, the visual axis (and center of the pupil) is located slightly superior nasal relative to the geometric center of the cornea. Scleral lenses, on the other hand, usually settle in an inferior temporal position based on the shape of the sclera. Thus, the center of the lens is inferior temporal in relation to the line of sight of the eye.

One method to find the location of the multifocal optics relative to the pupil involves employing over-topography of the settled lens on the eye. Using subtractive tangential maps makes it easy to find the centration point of the multifocal optics. If the visual axis is significantly decentered relative to the lens center in its settled position, there are manufacturers that offer decentered optics to align the multifocal add zone with the visual axis. If the lens is significantly decentered, it is unlikely that changes in power will improve visual performance.

In some cases, expanding the size of the distance or near zone, depending on the design, may help distance, near or both. This technique can also be used to check near zone size in comparison with pupil size. Too large of a near zone will reduce distance performance, and too small of a near zone will reduce near performance.

Push For Near or Far

In cases of insufficient near vision, push plus while performing an over-refraction at distance prior to making changes to the add power. If no plus is accepted, then adjust add power (particularly in aspheric designs) or add zone (more commonly in concentric designs). Additionally, flattening the base curve of a scleral lens while compensating for loss of sagittal depth in some designs will create additional plus, increasing magnification. Another option is switching lens designs. For example, if a center-distance design is selected first for both eyes, change the non-dominant eye to a center-near design to improve near vision.

If distance vision is poor, on the other hand, perform a spherocylindrical over-refraction at distance. This will help rule out residual astigmatism and flexure as causes of decreased vision. Assuming proper lens centration, the near zone size may need to be reduced in a center-near design or enlarged in a center-distance design. Decreasing the add power is another alternative if over-mapping demonstrates that the add zone size is appropriate. The add power may be decreased in the dominant eye and kept the same in the non-dominant eye.

Though multifocal optics add another layer of complexity to scleral lenses, the results are rewarding to patients and practitioners alike. Keep in mind that contact lens laboratories want you and your patients to be successful with their products and, as such, are a beneficial resource that should be explored. Consultants can help guide you through the fitting process and troubleshoot problems if and when they arises. Patients fit with scleral lenses are generally satisfied with the outcome, and those who wear lenses with multifocal optics are typically even more pleased. The age of multifocal scleral lenses has arrived. It’s up to you to be a part of it.

Dr. Gelles is director of the specialty contact lens division at the Cornea and Laser Eye Institute (CLEI) and the CLEI Center for Keratoconus in Teaneck, NJ.

Dr. Barnett is a principal optometrist at the UC Davis Eye Center in Sacramento, CA. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry (AAO), a diplomate of the American Board of Certification in Medical Optometry and a fellow of the British Contact Lens Association.

Dr. Jedlicka is an associate professor and chief of the cornea and contact lens service at the Indiana Univ. School of Optometry in Bloomington. He is a diplomate of the AAO’s Cornea, Contact Lens and Refractive Technologies section and a fellow of the Contact Lens Society of America.