I often come across eye care providers who primarily focus on the downsides of contact lenses, such as sterile corneal infiltrates, microbial keratitis and, in some clinics, limbal stem cell dysfunction. They often simply advise patients, “If you are going to wear contact lenses, switch to daily disposables and don’t sleep in them.” Although an understandable perspective—the two main risk factors for microbial keratitis are overnight wear and poor hygiene (often involving lens reuse)—today’s contact lens care landscape is not so cut and dry.1 We can serve our contact lens patients best by understanding the spectrum of lens care options and how to educate wearers appropriately.

| Internet Issues Today’s contact lens population is expanding to include more children and adults older than 50. We know little about the immune signatures of children and how they will respond to infection and inflammation; but in older adults, we often see worse corneal infection outcomes. This could possibly stem from adaptive immune responses mounting a more severe response or less defense against organisms, as well as a shift in the biome of the skin as patients age.15,16 |

Daily Disposable Dilemma

While epidemiological studies do not show a lower risk of microbial keratitis events such as bacterial, fungal and amoebic infections with daily disposables (although there is a reduced risk of sterile corneal infiltrates), research does show a reduced rate of severe infection and vision loss.1-3

This is, presumably, due to the modality’s reduced need for contact lens cases, which can be colonized by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other environmental organisms associated with more severe disease. Endogenous or skin-borne organisms such as Staphylococcus epidermidis. The latter are more common in cases of daily disposable–associated microbial keratitis.4

For many, this leads to an assumption that reducing lens care needs eliminates the complications of contact lenses.

But that’s not necessarily true. In a recent unpublished audit of contact lens wearers with Acanthamoeba keratitis, for example, researchers from Moorsfield Eye Hospital in London found about one-third of subjects wore daily disposables. Continued risk for infection exists, for three reasons:

- Daily disposable wearers may be tempted to misuse the lenses by over-wearing them and storing them in the lens packaging or another convenient vesicle or solution that contains no disinfectant.

- The increased risks associated with water-contact lens exposure during activities such as swimming, showering and using wet hands to manipulate lenses are likely just as prevalent in daily disposable lens patients as they are for reusable lens wearers.

- Because there are fewer lens care-related steps involved, daily disposable wearers may be less likely to recognize their lenses as medical devices. Instead, many may see them a something closer to a cosmetic product.

Daily disposable lens wearers are still at risk for microbial keratitis, especially if they do not wash their hands before handling the lenses.4 In addition, certain types of these lenses have been more difficult to handle and remove from the eye, often leading to adverse mechanical events, infection and inflammation.5

|

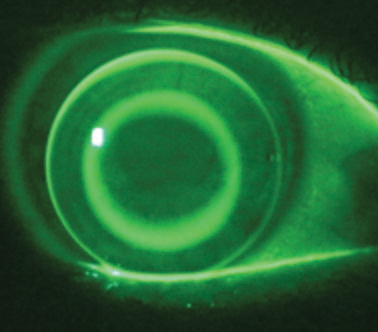

| Despite the reduced lens care needs of daily disposables, wearers are still at risk for microbial keratitis, as seen here. Photo: Jeffrey Sonsino, OD, and Shachar Tauber, MD |

In most cases, the benefits of daily disposables outweigh the risks. However, a large patient population of reusable lens wearers still exists, both by choice and because of the wider availability of lens prescriptions. As such, contact lens practitioners cannot ignore lens care needs for these modalities, which include most presbyopic and high sphere or cylinder power soft lenses and all rigid gas permeable (GP) lenses, including the expanding orthokeratology (ortho-K) market.

Solution Regulation

Lens care systems are primarily designed to reduce microbial contamination introduced during wear and handling. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) each specify the safety and efficacy requirements for lens care products to reach the market.

Historically, the ISO has had two pathways for lens care product approval: the stand-alone test and the regimen test. In the first, a solution must reduce Pseudomonas aeruginosa by an inoculum of 6 log units, Staphylococcus aureus and Serratia marcescans by 3 log units and Fusarium and Candida by 1 log unit. For the regimen test, administrators place a higher inoculum on the contact lens, and a solution cannot allow more than 10 colony-forming units of micro-organisms to remain on the lens.

Despite these regulations, highly publicized issues with contact lens disinfecting solutions began in the United Kingdom in the 1990s when chlorine disinfection tablets were associated with Acanthamoeba keratitis.6 In the 2000s, Bausch + Lomb withdrew its ReNu MoistureLoc solution when it caused an outbreak of Fusarium keratitis, and Advanced Medical Optics’ Complete MoisturePlus solution followed after reports of Acanthamoeba keratitis.7,8 Both outbreaks were associated with wearer hygiene issues (“topping off” lens solution was a common problem in both the Fusarium and Acanthamoeba keratitis outbreaks), prompting the FDA to consider “human factor engineering” to incorporate a margin of safety for how these products are used in the real world.

|

| While many of today’s patients opt for daily disposable lenses, don’t forget about those still in reusable modalities such as ortho-K lenses. Photo: John Mountford, Dip, App, Sc |

In 2008, these outbreaks prompted the FDA to hold a workshop in which they recommended:

- Acanthamoeba be added to the pool of organisms tested.

- Lens case and biofilm formation evaluations be added to the regimen test.

- Organic soil, a measure of lens handling contamination, be added to the stand-alone test.

- Solution products would include and specify a rub regimen on their labeling.

In 2014, the ISO updated the standards to include the evaluation of solutions in the presence of contact lenses and lens cases, as well as the addition of organic soil to testing regimens. However, the 2014 revision left out Acanthamoeba from the organisms included on the test panel. Acanthamoeba feeds on bacteria, and the ISO felt its growth would be limited by adequate antibacterial activity. However, research shows a high rate of culture-positive contact lens storage cases despite adherence to manufacturer guidelines.9-11

Contact lens manufacturers routinely test products against various strains and species of Acanthamoeba, but a lack of consistency in the testing regimens exists due to variables such as the species and strains tested, the methods of culturing Acanthamoeba trophozoites and the methods for inducing encystment.

Another ISO standard update in 2015 provided some clarity on this front by specifying a method for evaluating the encystment potential of Acanthamoeba. However, this excludes the evaluation of oxidative systems such as those using hydrogen peroxide that require special, vented lens cases, and the FDA has yet to adopt the method. Still, many hold out hope that the FDA will soon adopt testing guidelines that include the complete range of existing and new lens care products. This would provide us with a better understanding of each product’s performance and, hopefully, improve safety margins.

Wearer Behavior

Despite all the industry standards and the publicity of severe events, contact lens wearer behavior has changed little. A recent study reports a high incidence of all lens wearers using tap water in their care regimen.12 While GP lens wearers traditionally have used water to rinse off the sticky lens cleaner, non-scratch lenses clear of tear protein build-up—a new option in this modality—lowers the risk of infection significantly for this modality. Nonetheless, high oxygen permeable RGP, ortho-K and scleral lenses are all likely to be more problematic when water is used before lens insertion.

|  |

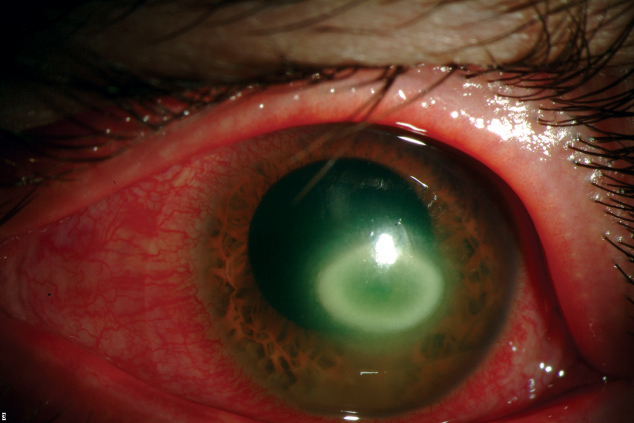

| Though contact lens manufacturers test their products against Acanthamoeba keratitis, seen here, a lack of consistency creates contamination issues. Photos: Christine W. Sindt, OD | |

Added to this, many patients do not understand the different lens care protocols between rigid and soft lenses, so there is a high potential for misinformation being spread from GP lens wearers to soft lens wearers.

The industry is making some progress in addressing these issues, however. Although FDA recommendations still include using water to rinse GP lenses, at least one large manufacturer has plans to move in the opposite direction. Additionally, the British Contact Lens Association, the American Academy of Optometry and the Cornea and Contact Lens Association of Australia have adopted a “no water” symbol for product packaging. Thus far, this visual cue is used on product packaging to alert contact lens wearers to the danger of non-sterile water on lenses and lens care regimens; those involved are hoping to incorporate the symbol into the printed literature and packaging of contact lens paraphernalia in the future.

The contact lens practitioner’s role in proper contact lens care is key, not only in tracking the patient’s ocular response to lens wear and care, but also in ensuring the patient is well educated on the lens care necessary for each modality. Whether wearing daily disposable or reusable lenses, a patient must understand that proper handling, cleaning, storage and replacement are all crucial factors that will dictate if the patient is successful in their contact lens wear.

Dr. Carnt is a Scientia Research Fellow at the UNSW School of Optometry and Vision Science. Previously, she worked in private practice in Australia and the UK before taking a position with the Brien Holden Vision Institute in Sydney in 1999, where she held a variety of roles, including principal investigator on contact lens clinical trials. She completed a PhD in Epidemiology of Contact Lens Related Infection and Inflammation in 2012.

1. Stapleton F, Keay L, Edwards K, et al. The incidence of contact lens-related microbial keratitis in Australia. Ophthalmol. 2008;115(10):1655-62. |