|

This 54-year-old man—an industrial worker—experienced an alkali burn while lowering a stainless steel die coated in aluminum particles into a tank containing sodium hydroxide. Though he was wearing safety glasses at the time, some of the liquid splashed into his right eye. He rinsed the affected eye for five to 10 minutes at a safety workstation, then returned to work despite having immediate pain and diminished vision; he sought care the following afternoon.

The local optometrist noted a pH of about 8 to 9, hand motion vision, two areas of symblepharon, a corneal epithelial defect and 4+ anterior chamber cell. The conjunctival adhesions were broken with a cotton-tipped applicator, atropine was instilled and a pressure patch was applied. He was seen on follow-up the next afternoon and had 5/200 vision with additional symblepharon formation, 3+ anterior chamber cell and a total corneal epithelial defect. His pH was rechecked and found to be about 7 to 8. He was referred to the hospital that day.

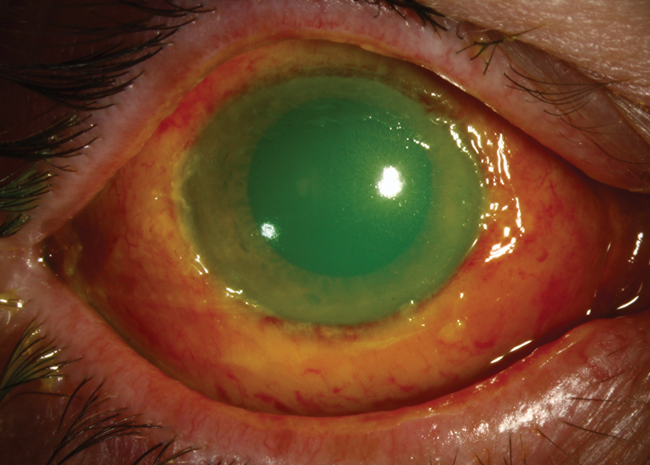

Upon arrival, his vision in the right eye was 20/40 and the tear film pH was 9. Slit lamp exam showed a total corneal epithelial defect and diffuse conjunctival injection and chemosis. The conjunctiva looked somewhat devascularized and white near the inferior limbus. The inferior conjunctival fornix was markedly shortened with a broad symblepharon stretched medially to the plica. The corneal stroma was slightly hazy. The anterior chamber was notable for 1+ cell and his intraocular pressure (IOP) was 25mm Hg by Tonopen.

A small metallic particle was removed from the inferior fornix at the slit lamp. The patient was placed in a supine position, anesthetized with tetracaine and the conjunctival fornices were swept with a glass rod. No additional foreign bodies were seen as a result.

To aid irrigation, a Morgan lens was placed on the eye; the ocular surface was then bathed in six liters of saline. The final pH was approximately 7. As this level was considered stable, an amniotic membrane was placed the following day. His vision at this point was 6/500.

He was started on an aggressive course of medications OD:

- Prednisolone acetate 1% ophthalmic suspension Q2h

- Medroxyprogesterone 1% ophthalmic suspension Q2h

- Ascorbic acid 10% ophthalmic solution Q2h

- Sodium citrate 10% in Celluvisc ophthalmic solution Q2h

- Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic solution QID

- Scopolamine 0.25% ophthalmic solution BID

- Doxycycline 100mg PO BID

- Sodium ascorbate 2,000mg PO BID

The patient was seen daily for a week, then monthly for IOP checks after his epithelium healed. He was lost to follow up at one year.

Fighting Fires on Many Fronts

Chemical burns represent 7% to 19% of all eye injuries, with about 15% to 20% of facial burns involving at least one eye.1 They can jeopardize many anterior segment structures, as well as the ocular adnexa, simultaneously. Alkali burns are considered the most dangerous, since they can penetrate deep into the eye, causing saponification of the cells. The damaged tissue in return releases proteolytic enzymes during an inflammatory response. There may be an acute IOP rise, as well as long-term IOP problems. Damage to the limbal stem cells will lead to vascularization of the cornea. Conjunctival damage causes scarring, fornix shortening, loss of goblet cells with associated ocular surface dryness and lid malposition.

Acute treatment includes copious irrigation with 20 or more liters of saline until pH reaches normal levels. It should continue to be checked every several hours to be sure it is stable. Ascorbate is added (oral and topical) to increase aqueous levels and reduce the incidence of corneal thinning and ulceration. Medroxyprogesterone is used to prevent deep ulceration and perforation of the cornea in severe alkali burns.2 While steroids reduce inflammatory cell infiltration and stabilize cell membranes, the clinician should remain vigilant for corneoscleral melts. Antibiotics are necessary on a cornea with epithelial defects, and antiglaucoma drops are prescribed if necessary.

Prognosis largely depends on the alkali material’s depth of penetration into the tissue. Patients should be monitored for stem cell dysfunction, glaucoma and dry eye-associated goblet cell dropout.

|

1. Singh P, Tyagi M, Kumar Y, Gupta KK, Sharma PD. Ocular chemical injuries and their management. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2013 May-Aug; 6(2): 83–86. |