Until recently, toric lenses made up a fraction of contact lens prescriptions. Over the last couple of years, however, toric lens use has grown substantially—now making up 13% of our total lens fits.1 For most eye care practitioners, toric contact lens patients often seem more demanding than spherical patients due to the extra time and effort that goes into fitting them. Fortunately, new lens types and modalities are simplifying the process and making these patients happier than ever, without much added chair time.

Twenty years ago, nearly every toric lens had to be custom ordered, and patients had to wait in our reception area for 20 minutes while the lens settled. Today, toric fitting sets allow for instant dispensing, and the lenses settle within minutes. With much advancement in this area, we have far fewer hurdles and can offer a higher standard of care to our patients. We live in a culture marked by instant gratification, which often presents difficulties when dealing with issues that can’t be immediately remedied. Fortunately, performing contact lens fittings from trial sets allows us to deliver care in mere minutes for the majority of our patients.

|

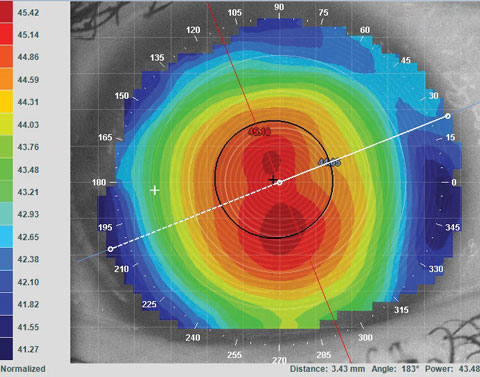

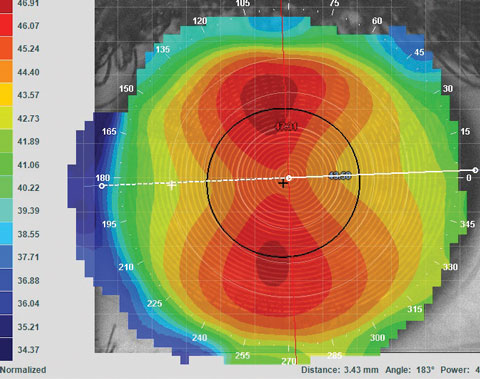

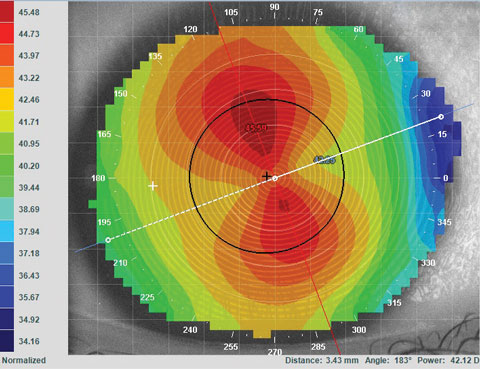

| Figs 1a. and 1b. Topography is essential for understanding distinctions in corneal shape that affect GP lens fitting. Patients with apical astigmatism (above) often do well with spherical lenses, while those with limbal astigmatism (below) often need a toric GP lens. |

|

In our practice, we still have patients with low degrees of astigmatism explain that past practitioners would not fit them with lenses because of their astigmatism. This is no longer the case, and it is our responsibility to show our patients the increasingly wide range of options they have—whether they’re astigmatic or not. Our toolboxes and lens options are ever increasing and—luckily for the less patient among us—the majority of these lenses take only minutes to fit.

Toricity Patterns

We are all familiar with astigmatism, but even within each subtype certain measures require a better understanding, as they impact how a patient sees out of their lenses. For example, it is important to distinguish the differences between limbus-to-limbus and central corneal astigmatism. Topography is essential to understanding these distinctions, as research shows significant changes occur in the shape of the cornea in the periphery, thus making conical sections (like with manual keratometry or autorefractor Ks) inadequate to predict the extent of corneal astigmatism.2 If a patient has a small pupil and central astigmatism during the refraction but a large pupil in her normal environment, her true amount of revealed astigmatism may vary.

This aspect of astigmatism management is also important for correctly fitting patients with gas permeable (GP) lenses. Patients with central corneal astigmatism, even with high power (>2.00D), may do very well with a spherical lens because the lens fits in the peripheral cornea in a more spherical nature. When patients have limbus-to-limbus astigmatism, on the other hand, they may reveal only -2.00D in the refraction but need a toric GP lens at the landing point of the lens (Figures 1a and b).

Other notable corneal shape features worth considering are those that are neither regular nor irregular in pattern. These patients may present with variable refractive axis with a minimally variable end point during the refraction. On topography, astigmatism in such patients may appear more like a distorted bow tie rather than a classic bow tie with-the-rule (WTR) or against-the-rule (ATR). These toric patients may benefit from a custom lens that can mask or vault the corneal shape.

Astigmatism in patients with a history of injury, surgery or disease can vary widely—ranging from normal to irregular. Rather than suggesting they all need a custom lens, we refer back to the refraction and corneal shape (see “Case Report: Custom vs. Convenience,” p. 12).

Although some patients may present with alarming findings on topography, they may have a relatively clean refraction and minimal aberrations. These patients may be suited for a standard soft lens (sphere or toric) rather than a custom lens, which might offer only a slight improvement over the standard lens. Of course, if a patient has a corneal alteration that would deem standard soft lenses impossible, custom lenses (GP sphere, GP toric, scleral or custom soft) must be employed.

Fitting Protocol

Every lens manufacturer has its own contact lens fitting guides, which tend to be accurate and worthwhile. Still, every practice should have a fitting protocol in place to maximize their success with any toric lens design:2

|

| Fig 2. Off WTR astigmatism: If this axis was 15, round closer to the 180, which would be axis 10. This gives us a final lens power for our patient of -1.50-0.75x180. |

1. For patients under 40, we always round up the sphere. Most trial toric lenses on the market only come in -0.50D. For example, we round the spherical power up to -1.50D in a patient with a prescription of -1.25-1.00x175.

2. When working with a patient with cylinder power that is between the options, we round down. Because soft contact lenses rotate about six degrees on average, rounding down minimizes visual distortions.3 As an example, we round the cylinder power down to -0.75D for a patient with a prescription of -1.25-1.00x175. Generally, if the sphere power is between stock powers and the cylinder power is between lens options, our practice is to round up with the sphere and down with the cylinder so that the spherical equivalent equals itself out.

3. For an axis that does not nail itself directly or clearly towards one, we round towards 180 for WTR and 90 for ATR. For a patient with a prescription of -1.25-1.00x175, we round the axis to 180 (Figure 2). For patients with presbyopia, we may elect to round down for the spherical component, but maintain the other two protocols.

Maintenance and Prescription Guidelines

Lens comfort is paramount for success in fitting toric lenses. Addressing and treating dry eye will decrease chances of eye rubbing, which can induce lens rotation and decrease vision quality. Unless the patient has a parameter that is not available in a daily disposable modality, we recommend dailies to provide the most comfortable contact lens wearing experience.

Case Report: Custom vs. Convenience Because his topography was not regular, we understood why his prior provider had placed him in a custom lens. We elected to trial fit him into standard single-use lenses with toric parameters to see how much improvement we could achieve with a slightly stiffer modulus daily lens. We were able to achieve 20/25+2 vision. After discussion with the patient about the slight improvement and possible decreased aberrations he might have with the custom lens vs. the daily disposable lens, the patient elected to go with the daily disposable due to convenience and simplicity. |

Toric single-use lenses are available from every major contact lens manufacturer. There now exist single-use silicone hydrogel lenses as well, which maintain the high oxygen permeability found in two-week or monthly lenses.

Although fitting most patients with toric powers is simpler and more direct than ever before, practitioners should always apply a greater degree of scrutiny for patients who have keratoconus or surgically altered eyes. These irregularities can account for significantly different needs and outcomes, typically requiring customized lenses to maintain corneal health and maximize visual outcomes. Most commonly, however, we find toric lenses provide much of what an average patient seeks. As a result of advancements in toric lenses over the last few years, we recommend and fit for toric single-use lenses far more often than ever before.

Growth in our practice may be partially attributable to patients who elect to be part time wearers—individuals who may have never considered wearing lenses in the past. We find that with the now possible simplified approach, our patients are pleased that we have taken the time for their torics, maximizing their comfort and vision—while also preventing contact lens dropouts in our practice.

Dr. Young is an associate at Specialty Eyecare Group in Seattle, WA. She specializes in dry eye and contact lenses. She graduated with honors from Pacific University and received the AOF award of Excellence in Contact Lens Patient Care.

Dr. Kading owns Specialty Eyecare Group, a Seattle-based practice with multiple locations. He specializes in anterior segment disease and custom contact lens fitting.

1. Morgan, P et al. International contact lens prescribing in 2015. Contact Lens Spectrum, January 2016.2. Read S, Collins MJ, Carney LG, Franklin RJ. The topography of the central and peripheral cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006 April;47:1404-15.

3. Momeni-Moghaddam H, Naroo SA, Askarizadeh F, Tahmasebi F. Comparison of fitting stability of the different soft toric contact lenses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2014 Oct;37(5):346-50.