We as optometrists hear complaints of dry, itchy eyes on a weekly basis, at least. Depending on the physical signs and symptoms that present with these reports, we can head down any of a dozen diagnostic roads—creating a potential management dilemma if we only focus on the dry eye signs and symptoms and fail to identify lid involvement as the true culprit. Blepharitis frequently compromises the ocular surface by creating an unstable tear film prone to evaporation. This can be especially troublesome in our contact lens wearers, and may encourage them to drop out of lens wear if they mistakenly blame the lens itself for a problem that is in fact much more complex.

Fortunately, most eye care practitioners (ECPs) have the diagnostic skills to uncover the underlying cause of these complaints. Take the following case, for example:

A 47-year-old male presented to the clinic with a primary complaint that his eyes have been itchy over the past few weeks to months. He revealed upon further questioning that he also had a secondary complaint of dry eyes for many years, for which he had been using an off-brand nighttime gel. The patient reported occasional but minimal success with the gel, was not taking any medications that may have been contributory to the case and did not report any significant medical conditions. His vision was 20/25 OD and 20/20 OS, while slit lamp examination revealed trace superficial punctate keratitis (SPK) in the inferior half of the cornea OU, along with grade II conjunctival injection OU. Osmolarity test (TearLab) findings were 312mOsm/L OD and 318mOsm/L OS.

|  |

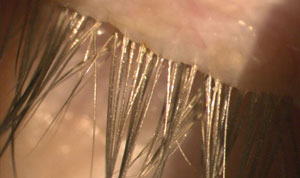

| Fig. 1. Exam findings of the right upper lid. What form of blepharitis does this patient likely have? | Fig. 2. A closer look at the right upper eyelashes reveals a clear sleeve of debris on multiple lashes. |

|  |

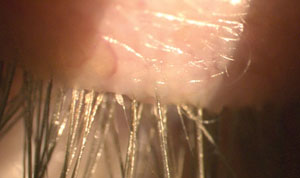

| Fig. 3. Lid examination findings of the left upper lid. | Fig. 4. Further examination of the lids reveals what condition? |

Lid evaluation revealed signs of blepharitis as the likely cause of the patient’s issue (Figures 1-4). The diagnosis may, however, be more complicated than that. Let’s delve into the details of lid margin disease before revisiting this case.

Differentiating the Condition

If a patient presents with generic complaints of ocular discomfort and dryness, many ECPs may be tempted to skip straight to diagnosis and management of ocular surface disease. Though initiating treatment can improve patient symptomology initially, failing to address any underlying eyelid pathology that may also exist can exacerbate the problem long-term. Blepharitis—inflammation of the lash follicle, lid margins or meibomian glands—can lead to a build-up of bacterial debris, keratinization of gland orifices and alterations of the normal tear composition. In contact lens wearers, this may result in lens discomfort, decreased wear time and lens wear dropout. Identifying the type of blepharitis present in a patient’s ocular environment is crucial for choosing the appropriate treatment regimen.

The three major forms of anterior blepharitis are staphylococcal, seborrheic, and Demodex blepharitis, also known as ocular demodicosis. Anterior blepharitis typically presents with symptoms of bilateral itchy, matted and/or crusty lid margins and ocular discomfort, often worse in the morning. Symptoms do not always correlate well with signs, so patients may occasionally present with asymptomatic disease. A careful anterior segment exam can help identify the type of blepharitis present.

Staphylococcal (or bacterial) blepharitis is commonly seen in clinical practice. Distinctive features include collarettes at the base of the lashes; those present at the tip of the lash indicate a more chronic condition, as it can take eyelashes about 16 weeks to grow to their typical length. Thickened, telangiectatic lid margins and conjunctival and corneal irritation or infection are also commonly encountered in cases of bacterial blepharitis. Chronic cases can also lead to notched, irregular lid margins that exacerbate the patient’s symptoms of dryness.

Staph. blepharitis is often caused by the normal flora present on the eyelid, which is most commonly either Staphylococcus epidermidis or Staphylococcus aureus. In these cases, the clinical signs are considered a result of cell-mediated responses to endotoxins that are produced in response to an overgrowth of the bacteria.1

Cases of seborrheic blepharitis tend to occur in an older population and clinically appear as a mix of dandruff and oily debris with slightly hyperemic upper lids. The term “scurf” has been applied to the scaly debris, with similar debris often seen throughout the patient’s eyebrows. More dermatologic in nature than Staph. blepharitis, this type is less frequently associated with infections or other corneal findings.1

Demodex overpopulation of the lids may also cause blepharitis. Two species of Demodex mites have been identified on the lids: Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis. The former, D. folliculorum, is primarily found in the eyelash follicles and around the base of the eyelashes and can cause chronic anterior blepharitis, while D. brevis can be found in the sebaceous and meibomian glands and can cause posterior blepharitis. Demodex mites create waste that accumulates as cylindrical dandruff around the base of the eyelashes, a finding that is pathognomonic for a Demodex infestation (Figures 5 and 6).2

Chronic Demodex infestations can result in trichiasis and madarosis, the latter of which is more commonly a result of Demodex than staphylococcal blepharitis.1,3 The mites can physically block the sebaceous ducts and cause hyperkeratinization of the lid margins. Definitive diagnosis of a Demodex infestation can be obtained by epilating a few lashes and examining them for mites under a microscope. Demodex blepharitis is considered by some clinicians to be underdiagnosed; one study reports that 100% of patients over 70 years of age have some amount of infestation.4 Demodex mites may also carry bacteria such as Staphylococcus sp., which can exacerbate the bacterial load on the lids and lashes. Several studies have also found a higher density of Demodex in patients with acne rosacea.1,2

Posterior blepharitis is characterized by inflammation and obstruction of the meibomian glands. Signs and symptoms include lid margin hyperemia, telangiectatic vessels along the lid margins, notching of the lid margins and inspissated meibomian gland orifices. Signs of posterior blepharitis are also evident in the tear film, including the saponification of tear film and also an oily appearance.

|

| Fig. 5. Demodex organism under low magnification. |

Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) is the most common cause of posterior blepharitis. If firm, mild pressure is applied directly to the lid margins, healthy meibomian gland secretions appear clear and oily, while more turbid secretions with opaque to yellow coloration are abnormal. Presence of acne rosacea may also lead to chronic posterior blepharitis, known as ocular rosacea.5 In some cases, clogged meibomian glands from posterior blepharitis can form a sterile, granulomatous chalazion, which presents as a painless, palpable lump in the eyelid. Chalazia may resolve with warm compresses, systemic tetracycline antibiotics or both; many cases, however, require steroid injection or surgical excision.

There are numerous other anterior segment findings that can result from blepharitis, such as SPK (particularly in the areas where the lid margins contact the cornea) and bulbar conjunctival hyperemia. A reduced tear break-up time can be a sign of posterior blepharitis resulting from MGD. Marginal corneal infiltrates and phlyctenules can occur in response to Staph. hypersensitivity in patients with Staph. blepharitis. Corneal pannus and corneal neovascularization are signs of chronic blepharitis and may be indicative of ocular rosacea. In cases of untreated chronic blepharitis, irreversible corneal scarring and subsequent vision loss can result.

Treatment

These conditions may coexist in many patients. Mainstay therapies for long-term blepharitis include lid hygiene efforts and heat therapy with warm compresses, followed by eyelid massage. Warm compress masks are convenient to use and hold heat longer than a warm, wet washcloth. This is important because it is recommended that the warm compresses remain heated to 45°C and be applied for a minimum of four minutes for optimal treatment.6 While baby shampoos can be recommended for lid scrubbing, certain branded lid scrubs are capable of targeting specific types of blepharitis as well. Regardless of the type of scrub recommendation, however, educate the patient that a gentle wipe across the lid margin is ideal, as more vigorous scrubbing can cause lid irritation and increase inflammation. Patient education should also speak to the chronic nature of the condition and emphasize the need for long-term maintenance of good eyelid and lash care.

|

| Fig. 6. Highly magnified picture of the Demodex organism. |

Lid and lash hygiene products that contain hypochlorous acid, such as Avenova (NovaBay) and HypoChlor (OcuSoft), are increasingly popular for blepharitis treatment. In vivo, hypochlorous acid is produced by neutrophils as part of the body’s natural defense system against infection. Hypochlorous acid is microbicidal, which is why lid hygiene products containing hypochlorous acid are an excellent option to decrease the microbial load on the eyelids and lashes. Furthermore, products containing hypochlorous acid are generally non-antibiotic antimicrobials and do not contribute to the ever-growing issue of antibiotic resistance.7,8

Acute flare-ups of staphylococcal blepharitis are treated using antibiotic ointments, such as erythromycin or bacitracin, massaged onto the lid margins. The short-term use of a topical antibiotic-steroid combination can also be considered in moderate-to-severe cases that present with concurrent corneal and conjunctival inflammation.

Seborrheic blepharitis is typically treated with dermatologic formation triamcinolone 0.1% cream or, in the case of patients who may have difficulties with keeping the ointment out of their eyes, Lotemax (loteprednol, Bausch + Lomb) gel or ointment.

Demodex blepharitis can be treated using in-office 50% tea tree oil applied to the lashes and eyebrows. Tea tree oil lid wipes such as Cliradex (Bio-Tissue) that are indicated for home use can also be recommended. Cliradex contains terpinen-4-ol, the most active ingredient of tea tree oil.4,9 In addition to tea tree oil treatment, patients should be directed to discard any current eye makeup and launder all bedding on a high heat setting to avoid reinfection. In-office treatments such as BlephEx (RySurg) may be a beneficial adjunct procedure in the management of all types of blepharitis. It cleans the lashes of both debris and collarettes and removes any bacterial biofilm from the lid margins.

Posterior blepharitis necessitates the use of warm compresses followed by manual expression or massage, though many more adjunct treatment options have come into play in recent years. Topical azithromycin 1% has proven effective in the treatment of signs and symptoms of MGD; its cost, however, has limited its use in some practices.10 Oral tetracyclines are beneficial for their anti-inflammatory properties, including the reduction of MMP-9.11 Studies also show low-dose doxycycline (sub-antimicrobial dose) improves the symptoms of MGD in affected patients with a lower incidence of side effects, resulting in better patient compliance.12 Pregnancy and childhood are contraindications for even the non-antimicrobial doses of tetracyclines. Oral azithromycin also shows promise for improving signs and symptoms of MGD, though further studies are necessary to better determine its ideal dosage for success.13

The role of omega-3 and omega-6 essential fatty acids in managing posterior blepharitis is ever-evolving. Well known for their anti-inflammatory properties, omega-3 fatty acids must exist in an adequate ratio, together with pro-inflammatory omega-6 fatty acids. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation with fish oil containing EPA and DHA is commonly recommended for patients with MGD. Research suggests gamma-linolenic acid (GLA), an omega-6 fatty acid, is effective in the management of blepharitis. One study found that dietary supplementation with fish oil and black currant seed oil (a known source of GLA) significantly improved both the signs and symptoms of ocular surface inflammation and irritation.14 HydroEye (ScienceBased Health) is one example of a supplement that contains both fish oil and black currant oil.14-16

|

| Fig. 7. Demodex blepharitis: Improvement but not complete resolution at follow up. |

|

| Fig. 8. Improvement and near resolution at the final follow up. Total resolution can be difficult to achieve and will require long-term chronic management. Without this, future flare-ups are much more likely. |

In-office warm compress application followed by manual gland expression behind the slit lamp can be performed using a Mastrota paddle (OcuSoft) or similar instrument. MiBoFlo Thermoflo (MiBo Medical Group) and LipiFlow (TearScience) are devices that use thermal energy to soften gland contents for removal. MiBoFlo is applied to the outside of the lid, together with slight pressure applied by the eye care practitioner, to encourage expression of the meibum, while the LipiFlow system applies heat from the palpebral side of the eyelids during application of pulsatile pressure on the outer surface of the lids to promote gland expression.17

Revisiting the Case

Ultimately, the patient described at the outset was diagnosed as having multiple forms of blepharitis, with Demodex predominating along with a secondary component of posterior blepharitis due to MGD. Careful epilation of several lashes and examination of their follicles under the microscope revealed such. The patient was treated with Cliradex pads twice daily for two weeks, then once daily for an additional two weeks. The patient was also instructed to use OcuSoft Lid Scrub Plus Foam once daily in the shower to cleanse his eyelids and lashes indefinitely. Warm compresses with a lipid-based artificial tear were also prescribed QID, and HydroEye fish oil soft gels were recommended for long-term supplementation to assist with alleviating further MGD. Multiple follow-up visits over the next three months demonstrated slow but continual improvement of the condition, with near resolution at the three-month follow-up appointment (Figures 7 and 8).

To ensure treatment success, clinicians must focus on the different forms of anterior and posterior blepharitis when patients present with ocular surface irritation, dry eyes and decreased contact lens wearing time. With a better understanding of these different forms of blepharitis and their appropriate treatments, eye care practitioners can improve their patients’ quality of life and, consequently, their ocular disease practice.

Dr. Harsch completed a cornea and contact lens residency at NSU Oklahoma College of Optometry. She is currently in practice at Nittany Eye Associates in State College, PA.

Dr. Stout recently completed a family practice residency with an emphasis in ocular disease at NSU Oklahoma College of Optometry. She is currently working as a clinical supervisor at the University of Waterloo School of Optometry and Vision Science.

Dr. Lighthizer is the assistant dean for clinical care services, director of continuing education and chief of both the specialty care clinic and the electrodiagnostics clinic at Northeastern State University (NSU) Oklahoma College of Optometry.

1. Gadaria-Rathod N, Fernandez K, Asbell P. Blepharitis. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS, ed. Ophthalmology, 4th edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014:177-9. 2. Cheng AMS, Sheha H, Tseng SCG. Recent advances on ocular Demodex infestation. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(4):295-300.

3. Jingbo L, Hosam S, Tseng SC. Pathogenic role of Demodex mites in blepharitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10(5):505-10.

4. Kemai M, Sümer Z, Toker MI, et al. The prevalence of Demodex folliculorum in blepharitis patients and the normal population. Ophthal Epidem. 2005;12(4):287-90.

5. Nijm LM. Blepharitis. In: Holland EJ, Mannis MJ, Lee WB. Ocular Surface Disease: Cornea, Conjunctiva and Tear Film. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2013:55-60.

6. Blackie CA, Solomon JD, Greiner JV, et al. Inner eyelid surface temperature as a function of warm compress methodology. Optom Vis Sci. 2008;85:675-83.

7. Ono T, Yamashita K, Murayama T, Sato T. Microbicidal effect of weak acid hypochlorous solution on various microorganisms. Biocontrol Science. 2012;17(3):129-33.

8. Debabov D, Noorbakhsh C, Wang L, et al. Avenova with Neutrox (pure 0.01% HOCl) compared with OTC produce (0.02% HOCl). NovaBay Pharmaceuticals:1-5.

9. Tighe S, Gao YY, Tseng SC. Terpinen-4-ol is the most active ingredient of tea tree oil to kill mites. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2013 Nov;2(7):2.

10. Optiz DL, Tyler KF. Efficacy of azithromycin 1% ophthalmic solution for treatment of ocular surface disease from posterior blepharitis. Clin Exp Optom. 2011;94:200-6.

11. Duncan K, Jeng BH. Medical management of blepharitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(4):289–94.

12. Yoo SE, Lee DC, Chang MH. The effect of low-dose doxycycline therapy in chronic meibomian gland dysfunction. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2005;19:258-63.

13. Kashkouli MB, Fazel AJ, Kiavash V, et al. Oral azithromycin versus doxycycline in meibomian gland dysfunction: a randomized double-masked open-label clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:199-204.

14. Sheppard JD Jr, Singh R, McClellan AJ, et al. Long-term supplementation with n-6 and n-3 PUFAs improves moderate-to-severe keratoconjunctivitis sicca: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Cornea. 2013;32(10):1297-304.

15. Horn M, Asbell P, Barry B. Omegas and dry eye: more knowledge, more questions. Optom & Vis Sci. 2015;92(9):948-56.

16. Pinna A, Piccinini P, Carta F. Effect of oral linoleic and ϒ-linolenic acid on meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2007:26(3):260-4.

17. Lane SS, Dubiner HB, Epstein RJ, et al. A new system, the LipiFlow, for the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2012;31:396–404.