| |

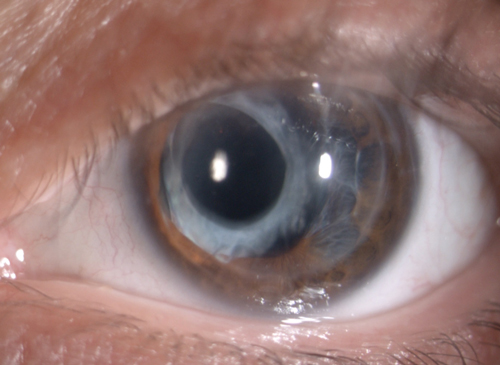

| Baseline OS. | |

| |

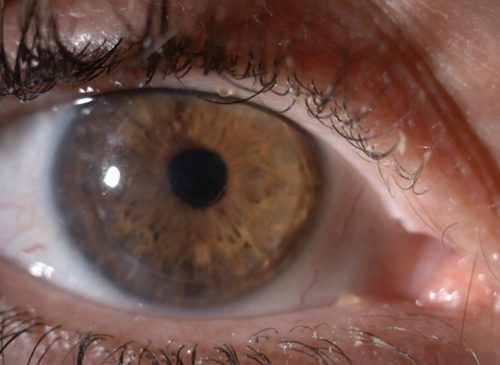

| The final lens fit OD. |

When fitting contact lenses for a compromised cornea, practitioners must remain aware of the complex challenges inherent in the processes that relate to vision, comfort and ocular health. First and foremost, patients expect good vision. In some cases, this is easy to achieve; in others, trial fitting is essential to finding the right lens. A patient can perceive and process basic visual information without having achieved adequate functional vision. Optical aberrations induced by a compromised ocular surface can create too much visual noise and distraction to allow the patient to be able to see comfortably.

Empirical fitting in such circumstances leaves too much unanswered; trial fitting allows you to determine the patient’s ability to tolerate the lens, assess lid comfort and perform an overrefraction to determine an expected visual outcome. The true test comes after the initial design is dispensed, however—only then can you adequately assess how well corneal health is maintained. Note, visual expectations vary based on a patient’s lifestyle and daily activities. Some—for example, surgeons and aviators—have extremely high visual demands that do not allow for subpar vision.

Beyond visual acuity, it is important consider on-eye comfort; an uncomfortable lens can have a life-altering impact on the patient. Patients have varying comfort thresholds: some will adapt just fine, while others can experience minor discomfort and a few may report excruciating pain. In patients who have undergone multiple surgical procedures and lens fits, managing patient expectations is especially fundamental to overcome pessimism and encourage good compliance.

From an ocular health standpoint, patients with compromised corneas can be especially sensitive to debris build-up under the lens or to lenses not staying clean throughout the day. They are also susceptible to dryness and discomfort with increased wearing time, particularly when blinking is reduced while performing prolonged near tasks. Thus, it is important to always be proactive about ocular allergies in patients with compromised corneas, as they have an especially difficult time tolerating allergic compromise.

Finally, ensure good corneal health with a lens and fit that offers adequate oxygen and minimal interference of normal corneal physiology. Similarly, as the CLEK study shows, apical clearance is important in patients with keratoconus and scarring.

Case in Point

In 2014, I was faced with one of the most unique and challenging cases I’ve encountered in my many years of practice. The patient’s history was truly stunning, as was his central corneal topography, which was the worst I have ever seen. Over the years, this keratoconus patient had undergone several surgeries, both in the US and internationally, aimed at improving his functional vision. In fact, he had already undergone RK three times in his right eye and once in his left eye, two corneal transplants, DALK/AK three times, and a cataract extraction.

To further complicate matters, the patient’s medical records contained several obvious inconsistencies, making it difficult to ascertain the rationale for so many surgeries and impossible to piece together an accurate timeline. Nonetheless, I was committed to finding a nonsurgical solution for this patient.

The 45-year-old Italian male was referred to my office in October 2014 to determine whether his vision could be improved without another surgery. He had recently presented to a local ophthalmologist here in the US with complaints of distorted vision. The MD concluded that the distorted vision was likely due to irregular astigmatism OD, which did not improve significantly with refraction. As such, the patient was now considering PTK. In light of his long and complicated surgical history, the ophthalmologist referred him to me with the hope that we might find a nonsurgical intervention.

The referring ophthalmologist diagnosed the patient with dry eye syndrome and recommended use of artificial tears three to four times per day. The patient was also administering prednisolone acetate 1% TID in the right eye to prevent complications from a recent cataract extraction. Systemic history included seasonal allergies.

| |

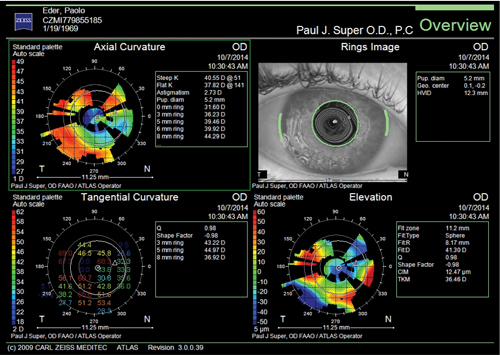

| Fig. 1. Topography OD. | |

| |

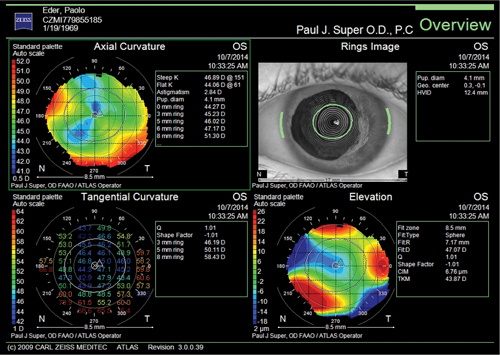

| Fig. 2. Topography OS. |

Diagnostic Data

The patient presented in my office with a corneal scar and irregular astigmatism OD as well as dry eye. The central zone of the cornea was not smooth. Best vision correction was as follows:

OD 20/70 PH 20/50+ +0.50/-2.75 x 170 20/40-3

OS 20/100 PH 20/25- -1.75/-1.75 x 045 20/ 30-1

IOP was 13mm Hg OD and 15mm Hg OS. Pachymetry revealed 396μm OD and 603μm OS. Corneal topography is shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Due to corneal instability and the patient’s irregular corneal surface, we initially tried three different approaches—all of which were unsuccessful. Scleral lens designs that vaulted the cornea caused a central air bubble, which consistently created epithelial loss. When we tried semi-scleral lens designs, they also failed due to spoiling and the cornea’s inability to tolerate the mechanical fit and physiological compromise of the lenses. Next, we tried to piggyback a scleral lens over a soft lens, but this too was unsuccessful. Table 1 illustrates our experiences during these trials.

During the course of fitting various diagnostic lenses, the patient made the decision to be fitted for his right eye.

At the follow-up visit, the patient displayed dry central pooling and central epithelial loss. I had exhausted all the options likely to work and had to try something outside of what I previously would have considered. Our next option was to design a lens that aligned over the central optical zone with lid attachment. We trialed the reverse geometry lenses shown in Table 2.

By December 10, 2014, we had designed and dispensed the lens. The reverse geometry corneal lens aligned over the central optical zone while the lid attachment allowed for a more customary fit profile. The patient reported the 11mm diameter of the lens was comfortable and examination indicated it supported the ocular health of the cornea. Subsequent follow-up visits showed good vision (i.e., 20/25) and lens toleration. There was no staining on removal and the patient reported he was able to wear the lens during waking hours.

| Table 1. Diagnostic Trial Lenses and Failed Lens Designs | |||||

| Eye: Lens | Base Curve | Overall Diameter | Power | Central Fit | Peripheral Fit |

| OD: Rose K2 XL | 7.4 | 14.6 | -2.00 | Slight Steep | Alignment with no seal off |

| OD: Rose K2 XL | 7.6 | 14.6 | -1.00 | Alignment | Good PC alignment with no seal off |

| OS: Rose K2 XL | 7.6 | 14.6 | -1.00 | Flat | Too much edge lift |

| OS: Rose K2 XL | 7.1 | 14.6 | -5.00 | Lens popped out | |

| OS: Rose K2 XL | 6.7 | 14.6 | -9.00 | Flat | Edge lift; steepen PC |

| Dispensed Lens OD: Rose K2 XL | 7.6 | 14.6 | -0.25 | Alignment | Good PC alignment with no seal off |

| Table 2. Reverse Geometry Lens Trials | |||||

| Right Eye | Base Curve | Overall Diameter | Power | Optic Zone | Peripheral Fit |

| 8.54 | 10.0 | +0.75 | 6.5 | 49.25/6.85/0.6 43.00/7.85/1.0 30.75/11/0.4 | |

| 8.54 | 11.0 | +1.75 | 6.5 | 49.25/6.85/0.6 43.00/7.85/1.0 30.75/11/0.4 | |

Discussion

It is well known that post-surgical corneas present specific challenges. Inadequate visual acuity and optical aberrations resulting from post-surgical procedures have a significant impact on quality of life. To complicate matters, these corneas tend to be unstable due to thickness and rigidity of the surface; thus, predicting outcomes can be difficult.

The challenge in this case was to fit a lens that would improve vision over a cornea that had already been surgically treated multiple times. I did not want to subject this patient to any more surgery. However, as I began fitting lenses, everything I thought would work didn’t work well at all.

After the first round of fitting, the patient returned complaining of a scratchy feeling, and that he couldn’t wear the lenses for more than a couple of hours. As such, regardless of the patient’s history, such a fit could not be considered a suitable solution. Qualitative responses are every bit as important as visual acuity when it comes to functional vision. Corneal anatomical shape factor, lid forces, optical power of the lens (i.e., thickness) and tear quality all impact outcomes. Furthermore, visual acuity alone does not provide enough tangible information on how a patient sees. It disregards visual noise.

We have to use all technologies, past and present, to find suitable solutions for patients like this one who continue to struggle with poor functional vision after surgery. As this case illustrates, we are sometimes called upon to dig deep into our toolboxes and try things we never previously considered. It can be time consuming and it can test our skills and fortitude as optometrists. However, it’s cases like this one that draw attention to our unique and specialized skill set and clearly demonstrate the profound effect that nonsurgical options can have on patients’ everyday lives.

Thank you to my friend and colleague Alan Saks, OD, for his help, as well as Art Epstein, OD, and Barry Eiden, OD, for their valuable suggestions.

Dr. Super is the founder of a specialty contact lens and primary care practice in Brentwood, Los Angeles; assistant clinical professor at Salus and Western College of Optometry; Immediate Past Chair of Optometry at Cedars Sinai Medical Center; and Optometry Advisor for Eye Defects Research Foundation.