|

Many patients who wear gas permeable (GP) lenses may at some point complain of ocular dryness during lens wear. Often, lens dryness is the result of changes in tear physiology. These changes can be a reaction to a variety of factors, including the type of lens material used, the presence of allergens (e.g., pollen, dust, pet dander), the use of certain medications, fluctuations in hormone levels and other age-related changes.

So, the question is: Can we do anything for these patients to make their lens wearing experience more comfortable? Do they need to discontinue wearing GP lenses altogether? In this column, we will explore some possible answers to these questions.

Stop, Look and Listen

First and foremost, if a GP patient complains of ocular surface dryness, it is important to ask the right questions and thoroughly evaluate their eye health before making any decisions. Some sample questions include:

• Do the dry eye symptoms occur only during lens wear, or do your eyes feel dry even after the lenses have been removed?

• Do your eyes feel progressively dryer as the day goes on, or is the level of dryness the same between the time you first apply the lenses and when you remove them?

• Is the dryness of sudden onset (i.e., did it start recently) or has it been present for a while?

• Do you have any other symptoms, such as ocular itchiness or a runny nose?

If the patient reports experiencing dry eye even with the lenses removed, there may be a problem with the ocular surface itself. Examine the ocular surface carefully—note the lid appearance and whether they have any capped meibomian glands or scalloped margins. Additionally, check their tear prism and consider administering a Schirmer’s test or the phenol thread test to determine aqueous tear production.

Check the cornea and conjunctiva with sodium fluorescein for staining and tear break-up time. If the patient shows any clinical signs of dry eye, start them on a treatment plan to ease the signs and symptoms of dryness. Treatment options may include artificial tears and gels, punctal plugs and/or prescription eye drops.

|

|

|

|

|

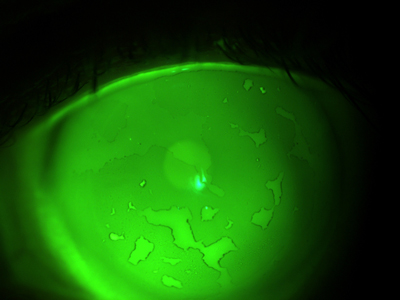

Fig. 1. Excess lipid and protein build-up can lead to non-wetting areas on a gas permeable lens. |

If a patient states that the lenses progressively dry out over the course of the day, schedule an exam late in the day to examine the lens surface after nearly a full day’s worth of wear. The contact lens may not have good surface wettability (i.e., the relationship between the surface tension of the liquid and the contact lens material). Lens deposits consisting of protein or lipids can prevent the lens surface from wetting well, thus reducing wear time and comfort. If this is the case, we need to determine the cause. If symptoms worsen as the day goes on, make certain the blink is complete, and evaluate the edge shape and contour to make certain it does not impede or inhibit the blink.

Some cases may stem from an incompatibility with the solution type. Some patients may have sensitivities to preservatives or other ingredients in multipurpose solutions. Consider changing the care system to see if the wetting improves. Other times, the non-wetting areas on the lens are a result of excess lipid and protein build-up (Figure 1).

If the patient changes care systems several times and still has a build-up problem, a different approach may be needed. If this is the case, consider a more aggressive cleaning regimen for the lenses, such as an enzymatic cleaner, extra strength cleaner or Progent (Menicon). Ocular surface disease may also contribute to the dryness, so consider treating the ocular surface as well, if necessary.

Another option is to change lenses. Patients who experience dry eye symptoms may benefit from a lower dK material because of its advantageous wettability properties.1 In theory, those GP materials with a lower wetting angle (i.e., less than 90 degrees) are thought to have better on-eye wettability.2

If the lens dryness is of sudden onset, further investigation is needed. Have they changed contact lens care systems or medications recently? Have any other health changes occurred? Ocular dryness is often related to allergies, and patients who take oral antihistamines are especially at risk for dryness. The drugs in this class reduce mucous and aqueous production, which cause dry eye complaints.3 Their activity may also decrease the aqueous component of the pre-corneal tear film. Other culprits include hypertensive medications, hormones, pain relievers, dermatologic drugs, chemotherapy drugs and antidepressants. In any case, in order to properly address the dryness, it is important to dig deep enough to identify its true cause.

Not Just a Number

One of the toughest cases of this kind to handle is GP lens-related dryness caused by age-related changes. It can be difficult to approach the topic of hormonal and other age-related changes with a patient. But, if extensive testing reveals the problems are a result of these changes, the conversation must be had. One possible way to approach it is to explain that as time goes on, the chemistry in a person’s tears naturally changes. Let the patient know they’re at the point in their life where their tears and their contact lenses are not interacting in the same manner as they used to.

Of course, this does not mean the patient cannot wear gas permeable lenses—we just need to be more creative and more vigilant. Again, try changing the material to something more wettable, and manage the ocular surface if that becomes a problem. If these options do not work, consider switching to a scleral lens instead. The tear reservoir between the cornea and the lens can act as a treatment for dry eye, especially aqueous insufficient type.

GP lens wearers who present with dry eyes can usually be easily managed once we as practitioners determine the cause of the dryness. Treating the ocular surface, changing lens materials and switching cleaning regimens are just some of many creative techniques to try. As with any problem, if you can figure out the cause and come up with a way to fix it, your patients—and you practice—will benefit. Give it a shot!

1. Pence N, Yeh FJ. Which is better? Selecting GP lens material. Contact Lens Spectrum 2013;28(10):17.

2. Bennett E, Henry V. Clinical Manual of Contact Lenses, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2014:94.

3. Hom M. Is it the medication? Optom Mgmt. 2000;35(2):92-6.