In the last few years, the use of scleral contact lenses has expanded beyond specialty contact lens centers into mainstream practices. Practitioners have numerous scleral lens options to choose from, as most GP lens manufacturers now offer at least one design. With this growth, the indications for scleral lens wear have begun to more clearly divide into two groups of scleral lens patient candidates: those for whom the lenses are medically necessary and others whose needs are purely refractive. This article will review the relevant indications for use of scleral contact lenses with respect to both groups.

Medically Necessary

From the early use of a “contact shell” to treat keratoconus in 1888, scleral contact lenses have come to occupy a distinctive yet comprehensive position in eye care, suited to treat a variety of eye conditions in patients whose corneal surfaces range from clinically normal all the way to extremely unique.1

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1. A decentered corneal GP lens secondary to corneal irregularity. Such a patient may experience a better fit with a scleral lens. |

• The irregular cornea. Scleral lenses are most commonly prescribed in the case of corneal irregularity, which induces higher-order aberrations; it can result from keratoconus, corneal surgery or trauma, or complications of otherwise routine surgery.

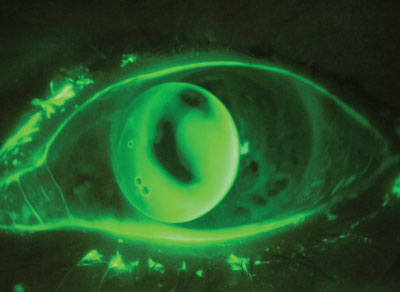

Such patients are often managed with corneal GP lenses; this modality’s ability to mask front surface corneal irregularity leads to dramatically improved vision. However, contact lens practitioners have struggled for decades to fit corneal GP lenses on patients with moderate to severe irregularity because of one inherent problem: the lenses’ small relative size forces them to distribute their weight directly onto the uneven corneal surface, which can lead to destabilization of the fit (Figure 1). Scleral contact lenses, on the other hand, vault over the cornea and rest on the sclera. As a result, centration and stability will remain unaffected.

Patients who have moderate to severe corneal irregularity, especially those who have previously failed in corneal GP lenses, make excellent candidates for scleral lenses. Be sure to explain to these patients why scleral lenses may be a better option than other contact lens modalities, and keep in mind that patients with small apertures or poor dexterity may have difficulty applying lenses. Patients may also be apprehensive about converting to a larger lens design. Demonstrating scleral lens comfort and stability in the office with a diagnostic lens will often result not only in patient acceptance but excitement.

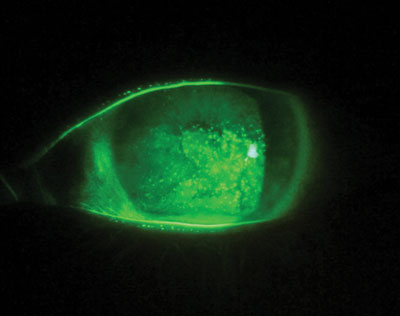

• Ocular surface disease. Another common reason for prescribing scleral lenses is to manage ocular surface disease. Patients with systemic conditions such as Sjögren’s syndrome, Graft-versus-host disease and Stevens-Johnson syndrome often present with comorbid ocular surface disease that can further decrease their quality of life and inhibit daily activities (Figure 2). For these patients, the rigid, curved shape of a scleral lens creates a liquid “cushion” that not only masks irregularity but also acts as liquid bandage that continuously bathes the anterior ocular surface. Scleral lenses also provide a barrier that protects the compromised anterior ocular surface from exposure.

|

|

| Fig. 2. Patients suffering from severe ocular surface disease often can benefit from scleral lens wear. |

|

Additionally, many patients with OSD may also present with corneal irregularity. With scleral lens use, patients with OSD typically experience quick, dramatic improvement in comfort and vision, allowing them to return to their normal routines and activities.

Be sure to work in tandem with any other eye care specialists who are managing the patient’s care; patients are often able to reduce their palliative and therapeutic ophthalmic drop regimen if they are successful with scleral lenses. Make sure to avoid any bearing of the lens on the cornea that could result in epithelial compromise.

Refractive Error

Though modern scleral lenses have been used successfully to manage medically related eye conditions for over 20 years, there has been relatively little research on the effects—especially long-term—of scleral lens use. Making the jump from using scleral lenses for patients who require them for medical reasons to patients with refractive error or dry eye is significant; thus, each practitioner needs to take into account the possible unknown risk of scleral lens use for patients where scleral lenses are merely an option rather than a necessity.

• GP burnout. Patients generally appreciate the sharp vision that corneal GP lenses provide, but some experience lens-related problems that limit wear time or lead to dropout. Patients with corneal GP lenses may complain of intermittent lens decentration or expulsion that interrupts wear time. This is especially problematic if the patient is active in sports. Corneal GP patients may also complain that occasional foreign bodies like dust or debris get trapped underneath the lens, leading to irritation that can force the patient to remove the lens for relief. Soft lenses can offer improved comfort or stability, but at the cost of sharp vision.

For such patients, scleral lenses can eliminate these symptoms while still providing the sharp vision that GP contact lenses offer. First and foremost, sclerals are inherently more comfortable to wear because they rest on the sclera, which is far less sensitive than the cornea. Scleral lenses also semi-seal to the eye and when fit correctly, will not reposition with eye movement or blinking. This fitting characteristic not only improves comfort, but stability as well. Additionally, the semi-sealed fit keeps environmental foreign bodies from getting underneath the lens.

Consider scleral contact lenses for patients who develop difficulties wearing their corneal GP lenses. Keep in mind that while you may have empirically ordered corneal lenses, scleral lenses will require a diagnostic lens fitting. Also, remember it’s possible that if you refit patients just out of their GP lenses, a power shift could occur over the first month during which their corneal curvature rebounds because they no longer have a lens that is supported by the cornea.

| |

| Fig. 3. Against-the-rule astigmatism is another likely clinical scenario where scleral lenses are worth considering. |

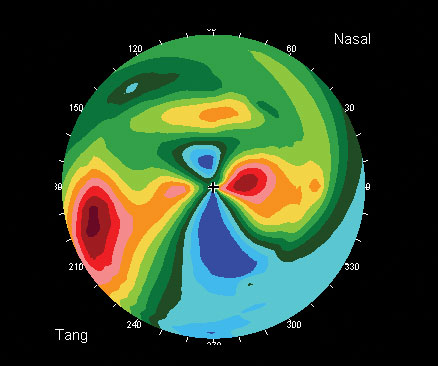

• Astigmatism. Patients with moderate to severe astigmatism may have a history of poor visual performance with traditional soft and corneal GP lenses. Soft lenses can be unstable for some patients, causing visual fluctuation that is frustrating for patient and practitioner alike.

Corneal GP lenses can effectively mask corneal astigmatism and are a great option for some of these unhappy soft lens patients; however, corneal GP lenses are also notoriously unstable for patients who have against-the-rule astigmatism, in which the horizontal meridian is steepest (Figure 3). In these patients, corneal GP lenses will often slide horizontally, causing lens instability.

Additionally, corneal GP lenses are not a great option for patients with lenticular astigmatism—they are unable to mask crystalline lens toricity with their tear lens, as they do for corneal toricity. Consequently, corneal GPs have to be manufactured with front surface toricity to correct the patient’s full refractive error. Just like soft lenses, front surface toric GP lenses can be unstable, leading to intermittent visual disturbances.

In contrast, the liquid reservoir that gets trapped underneath a scleral GP is able to mask corneal astigmatism, and the fit is stable regardless of astigmatic orientation because the lens fits the sclera, not the cornea. Front surface toricity can also be added to scleral lenses for cases of lenticular astigmatism. Unlike corneal GP lenses, ballasted scleral lenses are stable due to their large diameter and semi-sealed fit.

Patients with moderate to severe astigmatism, especially those who have failed in other traditional lens modalities, are good candidates for scleral lenses. Be sure to do a spherocylindrical over-refraction during the fitting and follow up. If the over-refraction yields astigmatism, check over-topography to make sure the lens isn’t flexing, which can induce astigmatism. Increasing center thickness can eliminate flexure. If the lens isn’t flexing, correct the residual astigmatism by adding front surface toricity. Spherocylindrical over-refraction at follow-up can allow you to fine tune the power for any induced cylinder secondary to lens rotation. This is more accurate than trying to apply LARS (left add, right subtract).

• Dry eye. Patients suffering from dry eye who require refractive correction may be candidates for scleral lenses, though this use is considered off-label. Scleral lenses have several advantages over traditional lenses for these patients: first, unlike soft contact lenses, GP material doesn’t dehydrate, which can lead to discomfort after several hours’ wear. Scleral lenses also hold a liquid reservoir, as mentioned earlier, which provides a continuously lubricating tear layer against the compromised ocular surface. Even patients who are successfully medically managing their dry eye condition may still have difficulty wearing other contact lenses and so could benefit from scleral lenses.

When fitting a dry eye patient, start with scleral lenses designed for the regular or normal cornea because you likely won’t need the size or geometry that scleral lens designs offer for fitting irregularity. Sonsino and Mathe reported that the amount of central vault does not seem to affect success.2 Make sure, however, that you completely vault the cornea to avoid bearing on a cornea surface that can be mildly comprised secondary to dryness.

Scleral lenses are a viable option for many patients who have struggled or been unsuccessful with soft, corneal GP or hybrid contact lenses. As such, with the growing popularity of these lenses it is recommended that you have a few diagnostic fitting sets in your practice that allow you to fit a broad spectrum of eyes—in particular, at least one diagnostic set designed for managing corneal irregularity or OSD and a second set that can be used for patients with regular corneas who have failed in traditional lens designs secondary to poor fit, irritation, uncorrected astigmatism or dryness.

Diameters for designs for corneal irregularity typically range from 16mm to 18mm, while diameters for refractive error and dry eye typically fall between 14.5mm and 16mm. Additionally, some designs are available with multifocal optics that can be added to the front surface for both for presbyopic patients with mild irregularity or those with regular corneas.

Overall, investigating scleral lenses to fit a broad spectrum of patients will improve your fitting success.

Dr. DeNaeyer is the clinical director for Arena Eye Surgeons in Columbus, Ohio, and a consultant to Visonary Optics, Bausch + Lomb and Aciont. You can contact him at [email protected].

1. Pearson, RM. Kalt. Keratoconus and the Contact Lens. Optometry and Vision Science. 1989;66(9):565-648.

2. Sonsino J, Mathe, DS. Central Vault in Dry Eye Patients Successfully Wearing Scleral Lens. Optom Vis Sci 2013. 90(9):e248-251.