Microbial keratitis is a well-known condition that has the potential to cause visual impairment and blindness. Corneal opacities, typically a sequela of infectious keratitis, are responsible for 5.1% of visual impairments worldwide and up to 10% of avoidable blindness in the world’s least developed countries.1,2 Diagnosis and timely initiation of appropriate antimicrobial treatment are imperative in patients presenting with a red, painful eye indicative of infection, as researchers speculate only 50% of eyes heal with good visual outcome without either.2,3 However, treating corneal infections is fraught with challenges and uncertainties that can make a clinician hesitant to move forward with any one management plan, even when confident of the diagnosis. This article addresses several of these roadblocks to help you treat microbial keratitis patients promptly and correctly.

Should I Culture?

In the past, textbooks and guides such as the Wills Eye Manual recommended culturing suspicious infectious keratitis prior to treatment.4 However, in practice, many start empirical treatment without culturing. The most recent edition of the Wills Eye Manual reflects this trend and recommends culturing infiltrates that are larger than 2mm, of a suspected unusual organism, in the visual axis or unresponsive to initial treatment.5

For example, a survey of community ophthalmologists in southern California found that 48.7% of corneal ulcers were treated without taking cultures.6 The discrepancy between formal recommendations and community practice may be due to the time and cost associated with performing cultures and maintaining materials and the high success rate of empirical antibiotic therapy.

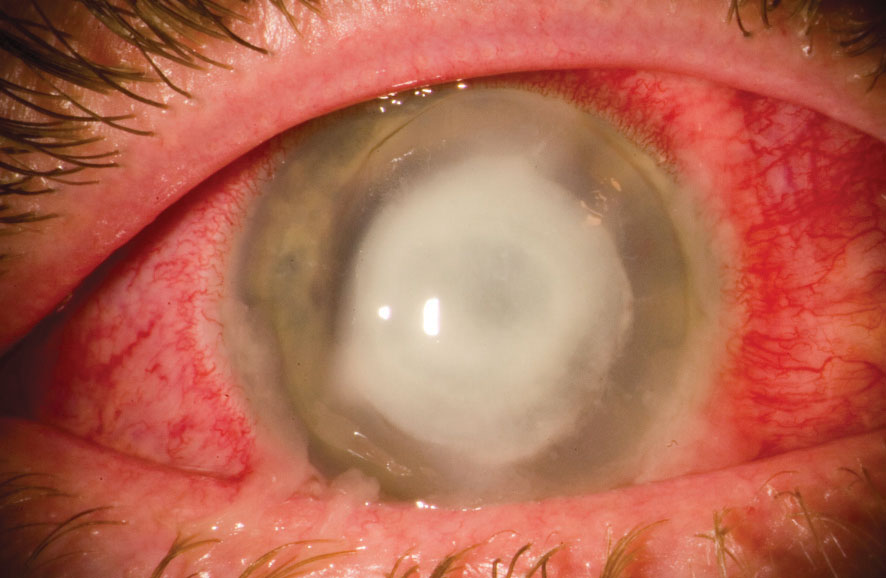

|

| This patient has an advanced P. aeruginosa corneal ulcer. Photo: Christopher Croasdale, MD |

In a comparison of a tertiary cornea clinic and general ophthalmology clinic, 10% of ulcers in the cornea clinic were resistant to empirical antibiotics, did not improve clinically and needed a therapy modification based on the culture and sensitivity testing. However, culture results in the general ophthalmology clinic did not lead to an alteration of therapy for patients.7 This discrepancy is likely due to the varying patient presentations between the cornea clinic and general ophthalmology clinic, the researchers note.7 The general clinic patients had smaller peripheral ulcers and were treated within three days of the onset of symptoms; the cornea clinic patients, however, were older, more likely to have corneal disease or previous surgery, larger central ulcers and referred an average of nine days after the onset of symptoms.7 Of the ulcers that needed modified treatment based on their culture and sensitivity testing, several were of unusual etiology (Aspergillus, Acanthamoeba and Actinomyces) and others were of S. epidermidis and resistant to fortified cefazolin.7 This study recommends those who treat severe cases culture most ulcers and general practitioners culture if the patient presents with a significant corneal ulcer.7

Begin with QuestionsGathering a thorough case history will help categorize a patient as having risk factors of infection. High-risk characteristics include a history of trauma, contact lens use, recurrent topical steroid use, immunosuppression and ocular surface disease.4 Patients without these histories are categorized as low risk. From here, clinicians can differentiate between a sterile infiltrate and an infectious keratitis and then plan the appropriate treatment approach. An epithelial defect overlying an infiltrate is generally present in microbial keratitis, although some Acanthamoeba keratitis and fungal infections, especially molds, can have an intact epithelium. The defect should be as large or larger than the infiltrate. When initial treatment fails, patients are usually referred to a cornea specialist for further investigation or treatment. However, current antibiotic therapy often complicates the question of whether to culture. Studies found that patients on antibiotic therapy were only slightly more likely to be culture negative. Nevertheless, the pathogen recovery may be somewhat delayed compared with cultures that were not pretreated. The delay in diagnosis does not necessarily lead to a negative outcome.8 In corneal ulcers with delayed healing, the causative organism may be fungal or protozoan. Thus, in patients not responsive to treatment, it is imperative to make a quick referral to a cornea specialist or have the patient cultured. |

Patients with corneal ulcers that are central in location, have a significant anterior chamber reaction or have corneal infiltrates larger than 4mm should be cultured, referred to a cornea specialist or both.3 In practice, clinicians should start considering culturing infiltrates larger than 2mm.9

How Should I Choose the Right Antibiotic?

Factors to consider when choosing an antibiotic treatment include broad-spectrum coverage, toxicity, availability, cost and region-specific epidemiology of pathogens.2 First-line treatment for most keratitis is topical and empirical. For bacterial keratitis, fourth-generation fluoroquinolone monotherapy is a common treatment approach. Fluoroquinolones are broad-spectrum antibacterials that cover gram-negative and anaerobic species responsible for ocular infections. They are also effective against a variety of gram-positive organisms; the spectrum of activity has improved with the modification in molecular structure of fourth-generation fluoroquinolones.10

Fortified topical antibiotics such as cefazolin sodium (50mg/mL) and fortified tobramycin sulfate (14mg/mL) are an alternate empirical treatment option. A randomized controlled trial found gatifloxacin monotherapy was equivalent to combination therapy with cefazolin and tobramycin treatment for nonperforated bacterial corneal ulcers.11 For patients with high-risk characteristics, another study recommends treatment with a fortified antibiotic, such as vancomycin, for gram-positive coverage, in addition to a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone, fortified aminoglycoside or fortified third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin for broad-spectrum gram-negative coverage.12

Because tetracyclines have anticollagenolytic activity and inhibit metalloproteinases, they can suppress connective tissue breakdown.2,13 Thus, oral tetracyclines such as doxycycline may help to stabilize the corneal melting possible in aggressive infections such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa.2,13 Despite the widespread use of adjuvant oral doxycycline among cornea specialists, high quality randomized controlled trials in humans do not exist to support its use.2

Patients with suspected fungal keratitis should be treated with topical natamycin 5%. Topical voriconazole, a newer generation triazole, has excellent ocular penetration compared with natamycin and is a good alternative. However, results from the Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial I demonstrate that natamycin was superior to voriconazole for topical treatment of fungal keratitis, and Fusarium keratitis in particular.2 The Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial II found no significant difference in the rate of perforation, visual acuity or rate of re-epithelization between adjuvant oral voriconazole or oral placebo. Subgroup analysis showed there may be a possible benefit to oral voriconazole in Fusarium ulcers. Thus, topical natamycin remains the treatment of choice for filamentous fungal keratitis, and the addition of oral voriconazole should be considered in Fusarium ulcers.2 Intrastromal injection of antifungal agents, such as voriconazole, may be useful for patients with deep recalcitrant fungal keratitis.2,14 While successful cases with intrastromal injections exist, randomized controlled trials are necessary to determine their benefit.2,14

In patients with suspicious herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis, topical treatments include antiviral medications such as trifluridine and ganciclovir. Topical corticosteroids are added in patients with HSV stromal keratitis. Steroids are typically avoided in HSV keratitis during the active infectious stage. Oral treatments such as oral acyclovir and valacyclovir have become more common in HSV keratitis secondary to the ocular toxicity that may develop with topical therapy. Topical medications may be added when oral medications are not adequate or in patients who are not good candidates for systemic therapy.2

Contact lens wearers are at risk of Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK). Biguanides and diamidines are the most effective cysticidal antiamebics for these cases. Commonly used biguanides include polyhexamethylene biguanide 0.02% to 0.06% and chlorhexidine 0.02% to 0.2%. Biguanides disrupt the cytoplasmic membrane and damage cell components and respiratory enzymes, all with low levels of corneal epithelial toxicity. They provide a synergistic effect when used in combination with diamidines, which include propamidine isethionate 0.1% and hexamidine 0.1%. Diamidines are effective against both the trophozoite and cystic forms of Acanthamoeba. First-line therapy is the combination of a biguanide and diamidine. Treatment with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, systemic steroids or other systemic immunosuppressive drugs such as cyclosporine may be needed in patients with extracorneal manifestations.15

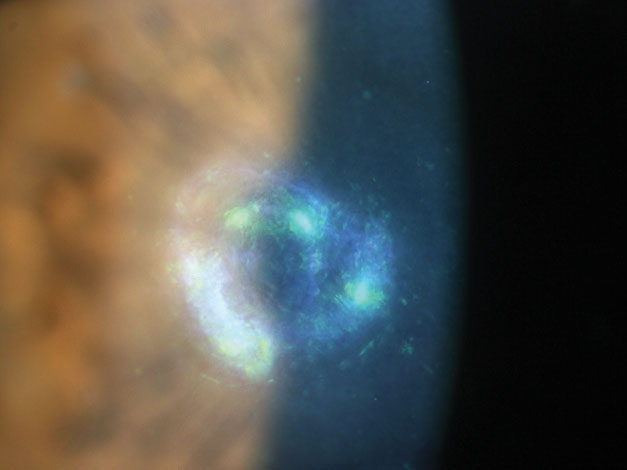

|

| Here is an example of a Nocardia-induced keratitis. Photo: Scott G. Hauswirth, OD, Richard Mangan, OD |

When Should I Add Corticosteroids?

The use of these medications in the treatment of infectious keratitis is controversial and, despite many studies researching the benefits of adding a corticosteroid to an antibiotic treatment, no formal standard of care exists for the use of steroids in bacterial keratitis.

Supporters for their adjunctive use rationalize that the addition will help minimize corneal scarring and opacification. Both infection and inflammation play a role in the pathogenesis and resulting clinical signs of infectious keratitis.16 In addition to the corneal injury induced by the bacteria, the host inflammatory response to the infection contributes to decreased corneal healing, ultimately leading to scarring.16 In the host, T-cells and macrophages respond to the bacterial invaders, producing cytokines. These then facilitate neutrophil migration and degranulation, leading platelet-activating factors to upregulate metalloproteinases and cause stromal necrosis.16 Because corticosteroids decrease inflammatory factors, using them in addition to antibiotics in the treatment of bacterial keratitis can limit the host’s inflammatory response and target the infection.16

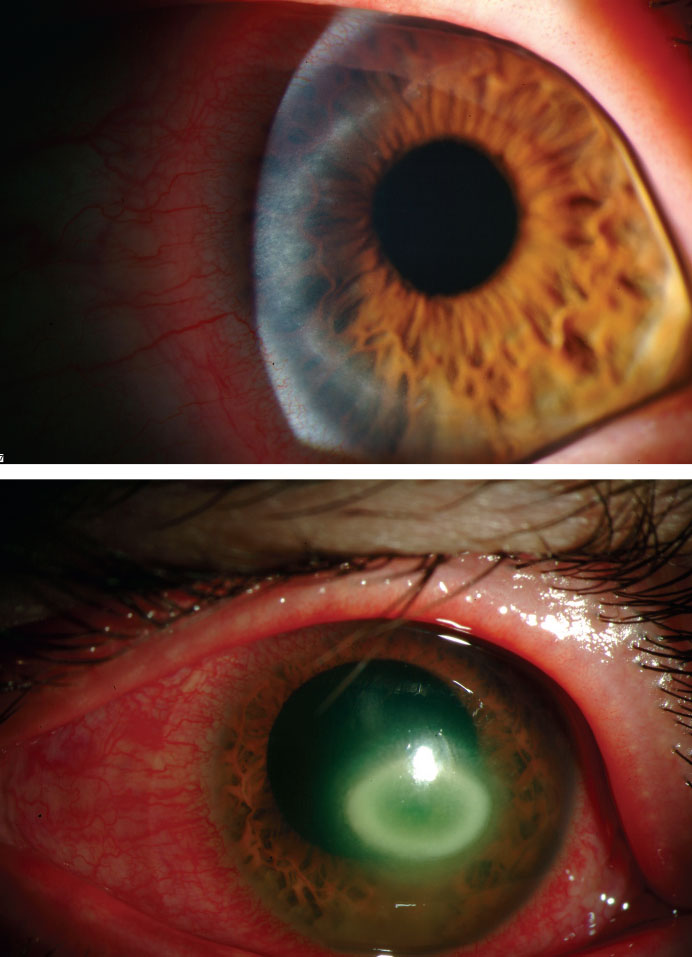

|

| These images depict the progression of AK over two months. Photos: Christine W. Sindt, OD |

Others believe the addition of a steroid may potentiate the bacterial infection and lead to corneal thinning and, possibly, stromal melt. Additionally, steroids may increase the duration of an infection or the risk of recurrent infection. Inappropriate addition of a steroid to antibiotic treatment may occur in patients with a fungal or Acanthamoeba infection, infections that are thought to be exacerbated by topical steroid use.16,17 However, no conclusive evidence exists to demonstrate whether the adjunctive use of topical steroids in bacterial keratitis is harmful or beneficial.

The Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial (SCUT), a large randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled trial that aimed to determine whether adjunctive topical steroids for bacterial keratitis improve long-term clinical outcomes, found no significant difference in best spectacle-corrected visual acuity (BSCVA), scar size or rate of perforation at three months between patients in the placebo and topical steroid adjunctive therapy groups.17 It also found no differences in healing rates or safety concerns with the use of adjunctive steroids.

The timing of adding a steroid may be crucial, research suggests. After studying the duration of topical antibiotic treatment before adding topical steroids, research shows a significant improvement in visual acuity when the topical steroid treatment was administered within two to three days of initiation of topical antibiotic treatment. Therefore, in non-Nocardia ulcers, steroids are beneficial when administered earlier, within two to three days, and neutral when administered later.18 Because the original SCUT results were inconclusive and the timing of steroid use was a non-prespecified group analysis, the authors recommend considering the results with caution and do not recommend changing clinical practice protocols.18

Clinicians should take these factors into consideration when treating various cases of bacterial keratitis with steroids:

Nocardia infections. Subgroup analyses showed that ulcers caused by Nocardia species had worse clinical outcomes with adjunctive steroid use. However, they found that patients in the adjunctive steroid treatment arm with worst baseline visual acuity (counting fingers or worse), ulcers located in and covering the central 4mm or ulcers with the deepest infiltrates at baseline experienced significant positive effects on their BSCVA.17 Subsequent analysis at 12 months revealed that steroids may be associated with improved long-term visual outcomes among non-Nocardia ulcers.17 Thus, it is possible that steroids require longer periods of time to reveal clinical benefits.19

Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Often associated with contact lens use in developed countries such as the United States, P. aeruginosa is a causative agent in a large proportion of bacterial keratitis.20 P. aeruginosa corneal ulcers are more severe, highly virulent, more difficult to treat and result in worse visual outcomes compared with other bacterial corneal ulcers. Because of this and animal studies describing increased recurrence rates of P. aeruginosa ulcers treated with steroids, many clinicians remain uncertain about using steroids in these corneal infections. However, the SCUT subanalysis found that when compared with other bacterial ulcers of similar severity, P. aeruginosa corneal ulcers responded better to treatment, resulting in greater improvement in visual acuity from presentation to three months.20 Additionally, the study did not find a significant difference in three-month BSCVA or infiltrate/scar size among the P. aeruginosa ulcers treated with adjunctive steroids compared with placebo, nor was there an increase in adverse events with steroid treatment.20

In practice, clinicians may consider adding a steroid to the antibiotic treatment of P. aeruginosa but should use clinical judgment and consider the specific corneal ulcer.

Acanthamoeba keratitis. In one review, researchers state that steroids are usually not required in AK cases that are diagnosed early and respond to antiamebic therapy. However, steroids may be useful when significant anterior segment inflammation exists to facilitate rapid resolution of symptoms. Again, clinicians should proceed with caution as steroids may worsen the condition by dampening the host’s inflammatory response.15 Evidence also suggests that steroid use may result in increased pathogenicity of the amoebas.15

Clinicians will never be able to avoid seeing corneal infections in their practice. While many controversies in corneal ulcer treatment can make these some of the toughest patients, a healthy mix of literature review and clinical acumen can go a long way. Knowing who needs a culture and how to tailor therapy based on initial response or the culture results will ensure patients receive the care they need and avoid negative outcomes.

Dr. Kwak is an Illinois College of Optometry graduate and completed her primary care residency at Salus University’s Pennsylvania College of Optometry. After years at an anterior segment practice, she recently joined Salus University as a clinical faculty member.

|

1. World Health Organization. Causes of blindness and visual impairment. www.who.int/blindness/causes/en. Accessed July 29, 2018. 2. Austin A, Lietman T, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Update on the management of infectious keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(11):1678-89. 3. Bennett HGB, Hay J, Kirkness CM, et al. Antimicrobial management of presumed microbial keratitis: guidelines for treatment of central and peripheral ulcers. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:137-45. 4. Friedberg MA, Rapuano CJ, eds. Wills Eye Hospital office and emergency room diagnosis and treatment of eye disease. First ed.Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1990:66. 5. Gerstenblith AT, Rabinowitz MP, eds. Wills Eye Hospital office and emergency room diagnosis and treatment of eye disease. Sixth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2012:435. 6. McDonnell PJ, Nobe J, Gauderman WJ, et al. Community care of corneal ulcers. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:531-8. 7. Rodman RC, Spisak S, Sugar A, et al. The utility of culturing corneal ulcers in a tertiary referral center versus a general ophthalmology clinic. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1897-1901. 8. Marangon FB, Miller D, Alfonso EC. Impact of prior therapy on the recovery and frequency of corneal pathogens. Cornea. 2004;23(2):158-64. 9. Weiner G. Confronting corneal ulcers: pinpointing etiology is crucial for treatment decision making. Eyenet. 2012;45-52. 10. Blondeau JM. Fluoroquinolones: mechanism of action, classification, and development of resistance. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49(2):S73-8. 11. Sharma N, Arora T, Jain V, et al. Gatifloxacin 0.3% versus fortified tobramycin-cefazolin in treating nonperforated bacterial corneal ulcers: randomized, controlled trial. Cornea. 2016;35(1):56-61. 12. Amescua G, Miller D, Alfonso EC. What is causing the corneal ulcer? Management strategies for unresponsive corneal ulceration. Eye. 2012;26:228-36. 13. McElvanney AM. Doxycycline in the management of Pseudomonas corneal melting: two case reports and a review of the literature. Eye Contact Lens. 2003;29(4):258-61. 14. Kalaiselvi G, Narayana S, Krishnan T, et al. Intrastromal voriconazole for deep recalcitrant fungal keratitis: a case series. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:195-8. 15. Maycock NJR, Jayaswal R. Update on Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Cornea. 2016;35(5):713-20. 16. Ni N, Srinivasan M, McLeod SD, et al. Use of adjunctive topical corticosteroids in bacterial keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016;27(4):353-7. 17. Srinivasan M, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, et al. Corticosteroids for bacterial keratitis: The Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial (SCUT). Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(2):143-50. 18. Ray KJ, Srinivasan M, Mascarenhas J, et al. Early addition of topical corticosteroids in the treatment of bacterial keratitis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(6):737-41. 19. Srinivasan M, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, et al. The Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial (SCUT): secondary 12-month clinical outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(2):327-33. 20. Sy A, Srinivasan M, Mascarenhas J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis: outcomes and response to corticosteroid treatment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(1):267-72. |