Study Backs Osmolarity Test

A new study recently published in Cornea adds to the growing body of evidence suggesting tear film osmolarity is a key indicator for dry eye disease (DED). Researchers looked at three groups of patients—clinically significant dry eye, symptoms-only dry eye and controls—and found the patients without clinically significant, but still symptomatic, dry eye had higher and more variable osmolarity measurements compared with the controls. These study results indicate changes in osmolarity precede clinical findings, the authors conclude, possibly opening doors for better and earlier diagnostics.1

|

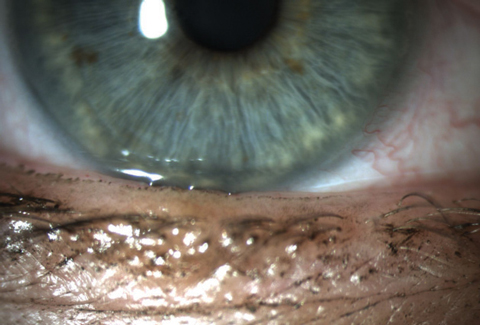

| Patients, such as this one, who are symptomatic but have no clinical signs might still have increased osmolarity, a possible indicator of early DED. Photo: Whitney Hauser, OD |

The study used the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire to evaluate for dry eye–related symptoms and tested patients for tear osmolarity and other objective measures such as tear break-up time and ocular surface, conjunctival and corneal staining. While it was no surprise patients with clinically significant DED had the highest tear osmolarity (312.0 ± 16.9mOsm/L) and control patients had the lowest (305.6 ± 9.7mOsm/L), the researchers were interested to find 13.5% of symptoms-only dry eye patients had an osmolarity score >320mOsm/L compared with just 2.4% of the controls.1

“High tear osmolarity in these individuals may foreshadow significant clinically apparent disease,” says Chandra Mickles, OD, MS, an associate professor at Nova Southeastern University College of Optometry. “Routine tear osmolarity testing within the context of the complete clinical picture may foster earlier diagnoses and ultimately improve outcomes.”

The researchers also found tear film osmolarity was associated with ocular discomfort symptom subscore, corneal staining score, conjunctival staining score, presence of central corneal staining and presence of corneal filaments—further supporting the hypothesis that osmolarity increases and causes ocular surface damage as DED worsens.1

DED is notoriously difficult to diagnose properly, given patient symptoms often do not correlate with clinical findings, the study authors said. Researchers continue to hunt for “one single quantitative metric that correlates with both symptoms and clinical findings of dry eye disease”—and many suspect osmolarity may be the answer.1

“Although it is clear that hyperosmolarity is at the core of dry eye disease, doctors remain unsure of the utility of tear film osmolarity testing in clinical practice,” says Dr. Mickles. “With these study results, doctors can put greater confidence in osmolarity measurement not only for patients with frank dry eye signs, but also for patients exhibiting symptoms without ocular surface staining.”

1. Mathews PM, Karakus S, Agrawal D. Tear osmolarity and correlation with ocular surface parameters in patients with dry eye. Cornea. 2017;36(11):1352-7.

High-energy Exposure May Cause More Haze Post-CXL

A recent study of corneal density after accelerated corneal collagen crosslinking (A-CXL) found that high-energy exposure may induce more haze in the early post-treatment period for patients with progressive keratoconus.1

Researchers from the University of Marmara’s Department of Ophthalmology in Turkey surveyed two groups of eyes, 20 in one and 24 in another. The former received A-CXL treatment with continuous ultraviolet-A (UVA) light exposure at 9mW/cm2 for 10 minutes adding up to a total energy dose of 5.4 J/cm2, and the latter received A-CXL with continuous UVA light exposure at 30mW/cm2 for four minutes and a total energy dose of 7.2 J/cm2.

Follow-up included corneal densitometry measurement, which is used to determine corneal transparency after refractive surgery and to monitor CXL’s effect. Researchers used Scheimpflug tomography to track corneal haze at one, three, six and 12 months post-treatment.

At the one-month follow-up, corneal density peaked in both groups. In the group treated with 9mW/cm2 A-CXL, these results plateaued until six months post-treatment, at which point they significantly decreased. The 30mW/cm2 group experienced a more gradual decrease in corneal densitometry throughout the follow-up. However, the mean change in density at the one- and three-month follow-ups was higher in the 30mW/cm2 A-CXL group than in the 9mW/cm2 A-CXL group, marking a possible correlation between higher-energy exposure and early postoperative haze.

Additionally, the corneal density of both groups returned to baseline after one year. According to the authors, this suggests the haze was transient rather than permanent. Researchers know that A-CXL affects corneal transparency, but these results show the change is reversible, at least in the first year, they note.

While the groups were initially treated with Vigamox drops (moxifloxacin hydrochloride 0.5%, Alcon), Lotemax drops (loteprednol etabonate 0.5%; Bausch + Lomb) and Refresh artificial tears (Allergan) for a brief period after undergoing A-CXL, the study notes that topical corticosteroids do not affect the course of postoperative transient haze.2

This study provides a look at the short-term effect of high-energy exposure on A-CXL, but it doesn’t address it in the long-term. The researchers view the one-year follow-up period as a limitation and would like to see future studies explore longer post-treatment periods.

1. Akkaya Turhan S, Toker E. Changes in corneal density after accelerated corneal collagen cross-linking with different irradiation intensities and energy exposures: 1-year follow-up. Cornea. 2017;36(11):1331–5.

2. Kim BZ, Jordan CA, McGhee CN, et al. Natural history of corneal haze after corneal collagen crosslinking in keratoconus using Scheimpflug analysis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2016;42:1053–9.

| In Brief Cheng AMS, Tseng SCG. Self-retained amniotic membrane combined with antiviral therapy for herpetic epithelial keratitis. Cornea. 2017;36(11):1383-6. Starting in 2018, the Centre for Contact Lens Research will become the Centre for Ocular Research and Education (CORE). The Center will undergo the name change as it enters its 30th year, citing efforts to work more closely with the optometric profession and improve vision health. Specifically, it plans to expand its scope of focus to include biosciences, clinical research and education. Centre for Contact Lens Research (CCLR) renamed Centre for Ocular Research & Education (CORE). Business Wire. October 11, 2017. Avaliable at www.businesswire.com/news/home/20171011005022/en/Centre-Contact-Lens-Research-CCLR-Renamed-Centre. Accessed October 23, 2017. |