|  |

In this age of digital devices, near vision demands have never been greater. For patients reaching presbyopia, the impairment of visual function during near tasks can be highly frustrating. Fortunately, advances in multifocal contact lens technology gives most patients the opportunity to meet their visual needs while maintaining freedom from spectacles.

Despite the arsenal of multifocal options available, many practitioners are still hesitant to fit them, instead recommending over-the-counter readers or monovision. However, studies show patients prefer the vision they get with multifocals to monovision.1

Gas permeable (GP) multifocals in particular can provide superior vision compared with their soft lens counterparts.2 And while fitting GP multifocal lenses can seem intimidating, understanding these concepts can help you get started on a path to success.

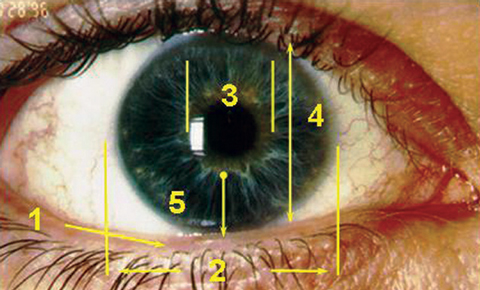

| Anatomical Considerations 1. Lid position.

|

Lens Designs

Presbyopic corneal GP lens designs are divided into two categories:

Non-segmented multifocals include aspheric and concentric designs, with the vast majority of contemporary multifocals being aspheric lenses.

Aspheric multifocals use a change in curvature on either surface of the lens to provide an increase in plus power. As the eccentricity (or rate of flattening) increases, greater effective add powers can be achieved. Aspheric multifocals are considered simultaneous vision designs, meaning both distance and near light rays are presented to the pupil simultaneously. This forces the brain to choose which light rays to accept. Although the transition between zones is generally smooth, higher add powers may still produce aberrations that affect distance vision. Accordingly, aspheric multifocals may perform better for low to medium adds.

Back-surface aspheric multifocals are center-distance designs with increasing add power as you move to the periphery of the lens. If back-surface asphericity alone does not provide sufficient near vision, additional asphericity or a concentric annular zone can be added to the front surface of the lens to increase add power. However, patients with a nearly spherical cornea may achieve a better fit with a front surface-only aspheric design, reducing the chances of corneal molding, which can occur with higher eccentricity back-surface aspheric lenses.

Segmented multifocals, also known as translating multifocals, have distinct areas of distance and near optics separated by lined or crescent shaped segments, allowing for crisp, uninterrupted vision at both distances. If intermediate vision is required, a smaller trifocal segment can be included as well. In primary gaze, the segment should be positioned at the inferior pupil margin so the near optics do not interfere with distance vision. Here, the inferior lens edge rests on the lower eyelid like a shelf. On downgaze, the eyelid then pushes the lens upward to move the near optics in front of the visual axis.

In addition to base curve, translating lenses use prism ballasting and truncated edges to help center the lens and stabilize rotation.

Patient Evaluation

The patient’s periocular and ocular features may dictate which GP multifocal lens you end up choosing. For example, the lid anatomy may immediately exclude some patients from a translating design. Proper lens translation requires a lower lid at or within 1mm of the lower limbus. Additionally, there should be good tonicity to allow the lens to rest on the lower lid without sliding between the lid and the globe. Smaller palpebral fissure size may also exclude translating lenses, which tend to ride high if the lower lid is above the limbus.

With aspheric lenses, the upper lid is of more importance for dictating lens diameter. If the upper lid is near the upper limbus, you can easily achieve a lid-attached fit using an average-to-larger diameter lens. Upper lids above the upper limbus may require a smaller diameter to achieve an interpalpebral fit.

As patients age, their pupil sizes typically decrease. For those with larger than average pupils, aspheric designs may yield ghosting or halos. Translating designs often work better in these cases, as large pupils allow for an easier transition from distance to near optics. Conversely, miotic pupils may have difficulty achieving the full power range towards the periphery of an aspheric design.

|

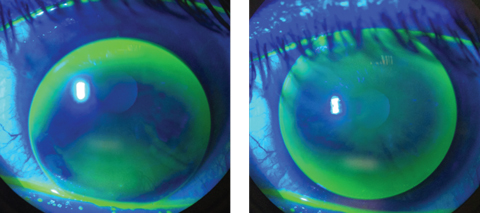

| An inferiorly decentered multifocal GP with excessive movement, at left, will cause blurred, fluctuating vision and discomfort. To improve fit and vision, steepen the base curve and increase the overall diameter, at right. Photos: Thuy-Lan Nguyen, OD |

Lens centration is also critical for success with multifocals. Aspheric multifocals are commonly fit steeper than flat K. By using a fitting nomogram based on the patient’s K readings, you can fit aspheric lenses empirically with success.3 Translating lenses, on the other hand, are better fit diagnostically so you can evaluate the movement on eye. These lenses are typically fit flatter than K and perform better on flatter corneas.

Setting Expectations

The best candidates for GP multifocals live balanced lifestyles without demanding perfect vision. Although many patients desire crisp vision at all distances, defining success with them ahead of time will help set proper expectations. Discussing the 80/20 rule with patients can also be helpful. Under this rule, a goal of 80% of daily activities should be achieved without any second thought, while the other 20% of the day may include mild difficulty at either distance or near. Make sure they understand that occasional use of magnification, illumination or over-glasses is not equivalent to failure.

Additionally, unlike single-vision lenses, it can take several weeks for the brain to adapt to the optics of multifocal lenses. During this time period, changes to the lens may be required to improve the fit or vision. Patients should expect at least one change to the lenses during the initial fitting.

The other main concern is that new wearers will not tolerate GP lenses in terms of initial comfort. Building up wear time is essential, similar to breaking in a new pair of dress shoes. It can be easy to underestimate a patient’s motivation and ability to adapt to GPs; however, a properly fit lens that provides great vision can make the process much easier.

Although less popular than soft multifocals, GPs can provide high quality vision at both distance and near for presbyopic patients. As with soft multifocals, determining patient needs and setting expectations is essential for success. Once you choose a design, you can use both diagnostic and empirical fitting methods with good success. When ordering empirically, corneal topography is a useful tool for both keratometry measurements and pupil size. If you need troubleshooting, lab consultants are a great resource to provide assistance.

1. Richdale K, Mitchell GL, Zadnik K. Comparison of multifocal and monovision soft contact lens corrections in patients with low astigmatic presbyopia. Optom Vis Sci. 2006;83:266-73. |