Over the years, I have frequently heard newly graduated eye care practitioners say, “I plan on joining a practice and staying up-to-date with all the latest research by participating in clinical studies.” But once reality sets in, the idea of clinical research may be set aside, largely because getting started seems like too much of a challenge. Once you take the first steps, however, you’ll learn how to balance the practice and research and how participating in clinical studies can be rewarding.

The Advantages of Getting Involved

There is always a need for clinical research in eye and vision care. Testing new strategies for the treatment or prevention of eye diseases requires clinical research, which, in turn, provides the basic ingredient for evidence-based medicine. Although training in clinical trial methodology is a lengthy process, there are many resources to help bring you up-to-speed in the fundamentals quickly. There are several advantages of being a clinical trial investigator, including:1

• Professional development. You can be on the cutting edge of your therapeutic area of expertise: meet other investigators, exchange ideas, plan future collaborations and work with investigational medications and processes that are not yet approved by the FDA.

• Professional recognition. You can use your role as an investigator to co-author articles for publication and be recognized as a thought leader within the medical community.

• Professional satisfaction. You may be able to offer your patients new medical alternatives that may only be available through participation in clinical trials.

• Compensation. Clinical trials may provide compensation for your time and resources.

• Advancement of medicine. You may become a leader in your field by potentially introducing breakthrough drugs and medical devices—products that could impact the health of people around the world—to market.

Levels of Evidence

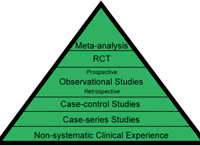

Before we jump into the best ways to get started, we must review the kinds of studies you may become involved with. Every day we hear experts say that the evidence should drive clinical care. But, what does that mean? Medical evidence should yield the data that guides practitioners in providing sound, informed patient care. And yes, there are levels of medical evidence, the most traditional description of which is the “evidence pyramid” (figure 1). The highest level of evidence comes from meta-analysis studies, in which multiple studies, often clinical trials, have been performed on a treatment for a disease state. The results from these studies are statistically combined to provide summary statistics. For example, one of the most dramatic meta- analysis study statistics comes from an analysis of the prevalence of worldwide visual impairment; findings of this study show that two-thirds of the visually impaired people in the world are women.2 In this analysis, multiple studies were combined and summarized to provide this staggering statistic.

The “Gold Standard” Clinical Trial

1. Evidence pyramid, with the highest level of evidence on the top.

When we think of levels of evidence, we often think of treatment, and in many cases meta-analysis is a challenge for multiple reasons. The “gold standard” treatment study is the randomized, double-blind (masked), controlled, multi-center clinical trial. In this trial, half of the subjects with the disease in question are randomized to the treatment group, and the other half are in the control group; each patient has a 50% chance of being in the treatment group. In the eye care arena, we use the term double-masked, rather than double-blind for the obvious reason—no one likes a “blind” eye study. So, in a double-masked study, neither the examiner nor the patient knows to which group the patient was assigned, which minimizes bias. A controlled or placebo controlled study is one in which the test article or active treatment is compared to a placebo. For instance, in an eye drop study, the placebo may be an artificial teardrop, saline or the vehicle (minus drug). In a study of an oral agent, the placebo is a tablet/capsule similar to the test agent (e.g., an olive oil capsule may be the placebo in a fish oil capsule study for dry eye). A study where either the clinician or the patient is aware of the treatment assignment is a single-masked trial. An example is a study of two marketed artificial tear products where the patient sees the bottle, but the doctor is unaware. An example of a study in which the doctor is aware, but the patient is not is procedure in which a collagen punctal plug is either fully inserted or partially inserted and discarded (sham procedure). While valuable to the eye care community, each of these studies present challenges, but let’s leave that discussion for later.

Studies Assessing Risk

Longitudinal cohort studies (following patients without disease for years) and retrospective case-control studies (evaluating past histories of patients with or without disease) are two types of studies that evaluate risk factors (prospective cohort) or the odds (case-control) of disease, given exposure. We often hear about case-control studies when there is an outbreak of a rare disease—for instance, salmonella as it relates to egg consumption or in eye care, Fusarium keratitis. These studies are designed to uncover what factors lead to the disease, and they provide good quality evidence. For example, cohort and case control studies have determined the “risk” of infectious keratitis to be higher with overnight (extended) contact lens wear than daily wear.3

Site Visits and Audits

Most industry-sponsored clinical trials and some developmental or pilot studies have a medical monitor. This individual will come to the office to review the source documents (examination forms) and the electronic data capture records (if this format is used). All regulatory materials, including the IRB documents and study correspondence will also be evaluated for compliance. Paperwork and documentation are critical and time intensive elements in a study, which is why you should always inquire up front about the time commitments so that you can budget appropriately.

Natural History Studies

Clinical studies (cohort studies) of groups of patients, if done over time, can provide meaningful information if little is known about a disease or its progression. Natural history studies track the natural time course of the disease and are best conducted when no treatment is provided; however, in some instances, withholding treatment is unethical. This presents a challenge in a natural history study. Studies of this type often are influenced by the clinician and more accurately, represent the clinician’s treatment patterns rather than disease progression. For this reason, natural history studies are often performed in clinical centers separate from patient care and involve doctors who aren’t the patient’s primary doctor; they may include “reading centers” for data, such as photographs or visual fields. A reading center is a centralized data collection center where digital data can be reviewed by single (or small groups) of masked readers. For example, fundus photographs are reviewed by readers masked to patient status in diabetic retinopathy studies.4

The Case Series

However, arguably the most important form of clinical study is the case series or individual case study. Although on the bottom of the evidence pyramid, these grass-roots ideas for diagnosis or management are tested in small groups of patients and can become the next diagnostic or therapeutic breakthrough. I found an example of clinically interesting case series early in my career in a series of patients with stage 2 macular holes who were undergoing surgery with subsequent application of autologous serum. In the series, the improvement was remarkable for most subjects.5 When the same surgical intervention was tested in a randomized, photo-reader masked clinical trial, improvement was found with surgical intervention, although the use of autologous serum as an adjunct did not provide additional benefit as suggested by the initial case series.6 Another, more recent example of a impactful case series is the use of topical azithromycin for meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) patients who are unresponsive to warm compress therapy.7 To date, a randomized, masked trial of these patients (unresponsive to conventional therapy) vs. a placebo has not been performed, and additional case series of this, as well as other therapeutic options for MGD are forthcoming.

Cowboy Science

Recently, one of my students asked, “If we are supposed to use tested evidence to manage patients, which doctors are doing these off-label studies?” It is a valid question. All pioneers of new techniques and therapies should follow these golden rules:

• Never subject the patient to a risk that outweighs the benefit.

• Always obtain written informed consent.

• Always document.

Keep in mind that without informed consent or documentation that is approved by a sanctioned review board, your “study” or “case series” would likely not be published in a highly rated peer-reviewed journal, as most journals have standards related to institutional review board approval and informed consent. But, that doesn’t mean that the idea can’t be presented to a company that manufactures a certain product for funding and access to individuals with proper experience in study design, regulatory paperwork and statistical analysis. Seek the expertise of individuals to help with this process if you have ideas for a case series or trial. I have seen examples of studies with a good design where the investigator failed to get informed consent from the participants, and unfortunately the studies were not published in the higher-ranked journals with greater impact.

Clinical Equipoise

Have you ever found yourself in a clinical conundrum, in which you did not know which treatment to prescribe or recommend? Or been in a situation where more than one treatment may have done the job and you were not sure which to choose? This is called clinical equipoise, when there is genuine uncertainty about the effectiveness of a particular treatment. As ethical concerns arise in human trials, efforts are made to reduce the bias of knowing the treatment status. In some instances, the investigator begins to believe that one arm of the trial is more beneficial than another, and for this reason, studies may be designed in a way that ensures that no one at the clinical center knows the treatment assignment (e.g., patients receive a treatment marked A or B). One person at the site may need to know for data entry purposes. This is why staff assignments must be carefully considered.

How to Get Started

The tools of the trade. Spend some time reviewing recently published studies in your area of interest. What tests are described in the methods section? For example, if an Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) chart is used to measure visual acuity, do you have the chart, the stand and the correct distance-to-chart marked? If it is an ocular surface disease study, do you have a dedicated 4°C refrigerator for liquid fluorescein and lissamine green? A dormitory-style small refrigerator works fine.

Prepare your materials. Participation in a clinical trial often requires the investigator to have an up-to-date curriculum vitae and financial disclosure. Also, there should be an area in the office—preferably under lock and key—where study medications and charts (or patient binders) will be kept.

Train your staff. Industry-sponsored clinical trials often require a study coordinator whose role is to manage, recruit and schedule study patients as well as handle the significant regulatory paperwork. This is often not a small task, especially if the study has competitive enrollment or a rapid timeline to completion. Some studies require separate individuals to enter data electronically and others to assign treatments, so you may have to appoint two staff members for a study. To avoid problems, always ask staff time requirements when agreeing to take part in a multi-centered study. There may also be additional training needed, such as internet-based data management or human subjects courses. These may be company-specific, but do take time to complete.

Document your patient pool. If you are interested in contact lens studies, you should be aware of how many patients in your practice are contact lens wearers, the types of lenses worn, the replacement schedules, coexisting disease (e.g., dry eye) and other characteristics that may be pertinent. You should also have a plan for how you would recruit patients. Will you send emails or letters to patients with certain diagnoses? Or, will you place an advertisement in your monthly patient newsletter? In addition to your recruitment plan, these statistics (patient numbers) are often used in site selection by companies. Understanding your practice demographic and having recruitment ideas beyond asking consecutive patients can prevent problems with recruitment as the study progresses.

Follow the protocol. In clinical studies, it is critical to follow the methods outlined in the protocol (detailed study description) provided by the sponsor. This may mean that a technique must be performed in a slightly different way than what you do clinically. For example, a tear break up time may require a Wratten filter and three consecutive timed readings with a stopwatch. Any variation on the protocol can seriously impact study findings. In fact, sites are often statistically monitored for significant differences between sites in a multi-centered study.

Once you’ve made all the appropriate arrangements, ask your industry representative to put you in contact with someone who has participated in studies for the company in the past. A few minutes on the phone can save you hours of time in the long run—learn from others’ experiences. Participating in clinical studies along with other O.D.s and M.D.s can be an extremely satisfying component of your professional career and, with effort and hope, can ultimately result in the most important outcome: improvement in patient care.

There are resources available to help you and your practice prepare for clinical trials. For example, the ARVO Foundation for Eye Research sponsors a clinical trials education series, which includes two-day, half–day and online course offerings. “This is the second time the half-day course has been offered through the ARVO Foundation for Eye Research Clinical Trials Education Series, and it has been very well received. It will probably be offered next year as well,” says Mae Gordon, Professor, Washington University St. Louis School of Medicine. Topics of the courses include: Day to Day Operation of Clinical Research Centers; Coordinator’s Point of View: Day-to-Day Operation; and Enrolling and Keeping Study Participants. For more information on future meetings and online offerings, visit www.arvo.org/eweb or www.arvo.org/ctes. Another website of interest is www.clinicaltrials.gov, which houses required registration for current clinical trials. ClinicalTrials.gov currently has 95,089 trials with locations in 174 countries and provides answers to frequently asked questions about clinical trials.

Available Resources

1. Clinical Trials. Available at: www.clinicaltrials.com. (Accessed July 2010).

2. Abou-Gareeb I, Lewallen S, Bassett K, Courtright P. Gender and blindness: a meta-analysis of population-based prevalence surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2001 Feb;8(1):39-56.

3. Stapleton F. Contact lens-related microbial keratitis: what can epidemiologic studies tell us? Eye Contact Lens. 2003 Jan;29(1 Suppl):S85-9; discussion S115-8, S192-4.

4. Danis RP. The clinical site-reading center partnership in clinical trials. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009 Dec;148(6):815-7.

5. Wells JA, Gregor ZJ. Surgical treatment of full-thickness macular holes using autologous serum. Eye (Lond).1996;10 (Pt 5):593-9.

6. Ezra E, Gregor ZJ; Morfields Macular Hole Study Group Report No1. Surgery for idiopathic full-thickness macular hole: two-year results of a randomized clinical trial comparing natural history, vitrectomy, and vitrectomy plus autologous serum: Morfields Macular Hole Study Group Report No 1. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004 Feb;122(2):224-36.

7. Foulks GN, Borchman D, Yappert M, et al. Topical azithromycin therapy for meibomian gland dysfunction: clinical response and lipid alterations. Cornea. 2010 Jul;29(7):781-8.

Dr. Nichols is associate professor at the Ohio State University College of Optometry. She lectures and writes extensively on ocular surface disease and has industry and nih funding to study dry eye. She is on the governing boards of the tear film and ocular surface society and the ocular surface society of optometry, and is a paid consultant to Allergan, Alcon, Inspire and Pfizer.