Conjunctivitis is a common, costly and, at times, confounding condition. It accounts for 1% of all primary care visits and costs the healthcare system anywhere from $377 to $857 million dollars annually.1 Known colloquially as “pink eye,” it can present with non-specific symptoms, such as lacrimation, grittiness, stinging and burning. Signs include hyperemia, chemosis and hemorrhages.2

While clinicians tend to rely on traditional signs—papillae, follicles, discharge, etc.—to distinguish the etiology, a recent meta-analysis suggests that these familiar signs and symptoms do not correlate with any one specific etiology of conjunctivitis.3 Consequently, clinicians are frequently misjudging viral, bacterial and sterile causes, with one study showing only 50% accuracy in diagnosing viral conjunctivitis when confirmed with laboratory testing.1 With so few standard tests available, a more thoughtful diagnosis requires knowledge of the prevalence, pathogens and clinical experience—with an eye for atypical presentations. Here, we take a look at what we know—and what remains to be resolved—about conjunctivitis and how best to distinguish between the condition’s various forms.

|

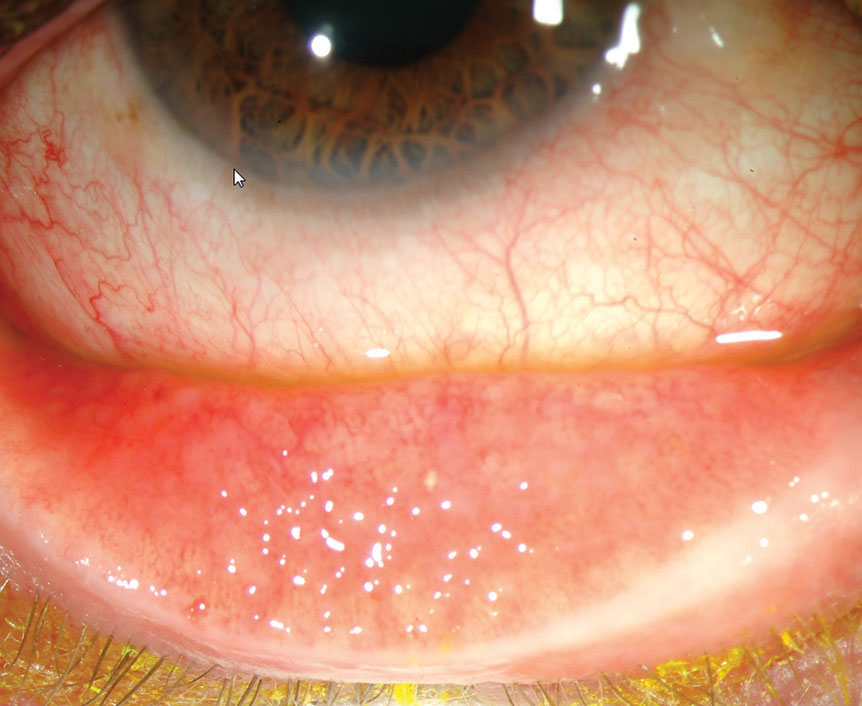

| Filled with lymphocytes and plasma cells, follicles tend to localize to the fornices and lack a central vessel. Photo: Marc Bloomenstein, OD |

Recognizing the Usual Suspects

Conjunctivitis has a host of etiologies, both infectious (viral and bacterial) and sterile (allergic, toxic, contact lens-related, etc.). The most common cause of infectious conjunctivitis is viral, responsible for up to 80% of acute cases of conjunctivitis.1,4 Bacterial conjunctivitis, while less common, is more likely to cause infection in children (50% to 75% of cases).1,5 Allergic conjunctivitis is the most common overall (up to 40% of all cases) but vastly under-diagnosed, with only about 10% of allergy sufferers with acute ocular symptoms seeking medical care.1,5 With each case of conjunctivitis, clinicians must carefully judge the whole clinical picture to uncover the true etiology.

Viral conjunctivitis. While a wide variety of viruses are implicated in this condition, the most common culprit by far is the adenovirus.6 Viruses that infect the conjunctiva less frequently include herpes simplex virus (often with associated keratitis), varicella-zoster, picornavirus, influenza A, Epstein-Barr, poxvirus, Newcastle disease and, rarely, HIV.7,8

Adenovirus is a nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus that can survive on dry surfaces for up to seven weeks.2 The incubation period for the virus is five to 12 days, meaning that patients often shed the active virus in advance of symptoms. Carriers are contagious for a period of 10 to 12 days, with symptoms sometimes lasting up to three weeks, an ample amount of time to spread the condition. Patients and family should be counseled accordingly.

The consequent non-specific acute follicular conjunctivitis is the most common type of viral conjunctivitis and usually results in mild ocular involvement with concurrent systemic findings, such as a sore throat or cold. Pharyngoconjunctival fever (PCF), caused by adenovirus strains 3, 4 and 7, most commonly affects children. It is usually associated with mild pharyngitis and a low-grade fever and often spreads within families.2,6 Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC), caused by adenovirus strains 8, 19 and 37, is the most severe type of viral conjunctivitis, typically occurs in middle-aged adults (men and women equally) and is most likely to involve corneal changes.2,6

Signs of viral conjunctivitis include prominent conjunctival hyperemia and follicles, lid edema and pre-auricular lymphadenopathy.2 In severe cases, conjunctival hemorrhages, pseudomembranes and true membranes may also be observed. Keratitis is seen in a third of cases and ranges from punctate staining to subepithelial infiltrates—signs representative of an immune response to the virus. Watery discharge may also be noted.2

The Treatment DilemmaProper diagnosis is critical to avoid unnecessary therapy and antibiotic resistance. Since both types of infectious conjunctivitis resolve spontaneously between seven to 14 days, clinicians should use antibiotic therapy judiciously. Unfortunately, treatment is often mandatory before children can return to school; this approach encourages unnecessary therapy and can send the child back to school well within the period of contagion. Furthermore, patients of all ages often expect therapy regardless of etiology and efficacy and will seek care at another provider’s office if not properly educated before leaving your office empty-handed. If treatment is indicated for bacterial infections, fluoroquinolones can combat the most common causative agents with little resistance. A potent antibiotic at the appropriate dosage is critical in eliminating the pathogen before it has the opportunity to mutate. Antibiotic therapy should never be reduced below the therapeutic dose, as this can further contribute to antibiotic resistance. |

Acute bacterial conjunctivitis. This is a common, often self-limiting condition that affects all races and genders. It is caused by direct contact with infected secretions, most commonly Streptococcus pneumoiae, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus and Moraxella catarrhalis, with the first two agents comprising 85% to 98% of all infections.9 However, hyperacute infections with Neisseria gonorrhoeae pose a far greater threat to sight.1 Infections with methicillin-resistant Staph. aureus (MRSA) are also of increasing concern in the general population. Molluscum contagiosum and microsporidia should be considered as possible etiologies as well.10

The condition typically presents with conjunctival injection, papillae and mucopurulent discharge. In severe cases, the patient may present with eyelid edema and erythema. Hyperacute purulent discharge is associated with infections by gonococcal or meningococcal bacteria, predominantly in infants born to infected mothers or adults infected via sexual contact.1 This is a serious infection that may develop a perforating keratitis within 48 hours.1 Chlamydia trachomatis infections are also possible, often with corneal involvement.1 Coinfection with gonorrhea and chlamydia is common, and clinicians should initiate treatment for both conditions if either is found.

Finally, blepharoconjunctivitis, often mild and overlooked, involves the interaction between lid margin secretions, microbial organisms and tear film abnormalities. This causes a chronic and episodic conjunctivitis.11

Allergic conjunctivitis. This comes in several varieties, each mediated by a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction to an environmental immune mediator. The allergen reacts with IgE antibodies, stimulates mast cell degranulation and the release of inflammatory modulators and causes a host of symptoms traditionally associated with allergic conjunctivitis.6

Simple allergic conjunctivitis is caused by a reaction to an environmental allergen, such as pollen, or to eye medications or solutions or to the preservatives contained within.2,6 Seasonal conjunctivitis refers to the exacerbation of allergic symptoms most frequently in the spring and summer as the result of tree and grass pollens, while perennial conjunctivitis presents symptoms year-round as the result of house dust mites, animal dander and fungal allergens.2

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) is a severe allergic inflammatory condition that mainly affects young males, with an average onset of five to seven years old.3 The condition is often associated with personal or family history of VKC or other atopies (e.g., asthma or eczema). While the condition often resolves in their late teens, some of these patients go on to develop atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC), a rare, bilateral disease with onset in late adolescence to adulthood. The condition is marked by chronic and unremitting conjunctival inflammation in patients with a history of atopy elsewhere, often dermatologic.2,6 Symptoms of VKC and AKC are similar, though those associated with AKC are more severe and unremitting.

Giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC) involves a combination of an allergic reaction and a mechanical irritation from a foreign body (in most cases, a contact lens).

Signs of allergic conjunctivitis include redness, itching and chemosis. Watering may also be noted and is associated with nasal discharge. VKC may present with a collection of eosinophils at the limbus (Horner-Trantas dots) and large papules under the conjunctiva. No preauricular node is typically noted.

|

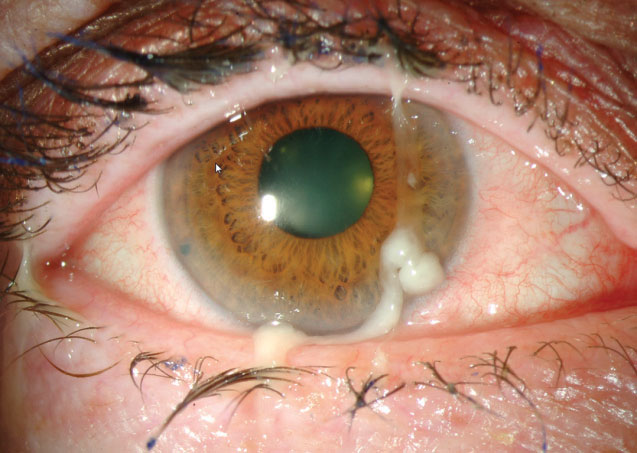

| Papillae often arrange in a cobblestone configuration of flattened nodules with a central vascular core. Photo: Marc Bloomenstein, OD |

Atypical Presentations

Other non-infectious forms of conjunctivitis can include contact lens-related, mechanical/traumatic (including trichiasis, ectropion and entropion), toxic, and neonatal.6

Exam Pointers

Clinicians performing adnexal examination should look at the periorbital skin and lymph nodes. Herpetic conjunctivitis may present with lid involvement before (simplex) or after (zoster) conjunctival involvement. Periorbital edema could point to a viral etiology. Lymphadenopathy is also most likely to occur in viral infections (EKC more so than PCF), though it may be noted in severe bacterial infections, chlamydial infections and Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome as well. The preauricular node is typically affected, though clinicians should also check the submandibular in all cases of conjunctivitis of unknown etiology. Tonsillar nodes may also give an indication of previous or current infection with influenza or non-influenza viruses. Clinicians should also perform an out-of-slit lamp view of the pattern of injection, so as not to lose the proverbial forest for the trees; viral infections may initially have more inflammation and injection inferiorly than superiorly, though severe cases will appear more diffuse.1

Conjunctival lumps and bumps may point to a cause, though not always. Bacterial and allergic conjunctivitis tend to present with a papillary reaction—a cobblestone arrangement of flattened nodules with central vascular cores.10 Papillae are more generalized markers of inflammation, while follicles are more diagnostic of a particular brand of inflammation, occuring mainly in viral, toxic and chlamydial infections. Follicles—filled with lymphocytes and plasma cells—tend to localize to the fornices, be smaller and lack a central vessel.2,12 As follicles associated usually tend to present inferiorly, while papillary reaction are often most pronounced on the upper tarsal plate, lid eversions can hold important diagnostic clues and should be performed on every patient. Chlamydial conjunctivitis classically presents with a mixed papillary or follicular response, worse inferiorly, in the context of a chronic, low-grade conjunctivitis.

Discharge can narrow the differential causes, as watery discharge is more indicative of viral conjunctivitis, while purulent or mucopurulent discharge is often associated with bacterial conjunctivitis. Hyperacute conjunctivitis tends to be associated with copious amounts of discharge that reappears immediately after wiping it away. Allergic conjunctivitis is also associated with nasal discharge due to the systemic association. The type of discharge should not be considered in isolation, as research shows it is not specific to any class of conjunctivitis.1 Any eye under stress will self-lubricate as a means of protection.13,14

Corneal changes may give further insight as well. Subepithelial infiltrates are associated with EKC and present several days into the infectious period. Bacterial conjunctivitis typically does not present with corneal findings, though serious infections can cause corneal infiltrates and, in some cases, hypopyons.15 VKC can present with a shield ulcer secondary to the close apposition between the conjunctiva and the cornea. Chlamydial infections may present with peripheral corneal infiltrates.1

Even knowing these common signs and symptoms, clinicians often have to look beyond the obvious to ensure the right diagnosis by obtaining the following:

|

| Purulent or mucopurulent discharge is often associated with bacterial conjunctivitis. Photo: Marc Bloomenstein, OD |

Patient history. While signs and symptoms may not be diagnostic for an etiology, patient history can provide invaluable clues about the cause of conjunctivitis.

Data as simple as a patient’s age or the time of year can help to narrow down the differential diagnosis. Viral conjunctivitis is more common in adults, while bacterial conjunctivitis is more common in children. One in eight children has an episode every year, with five million pediatric cases reported annually.9 Allergic conjunctivitis has little preponderance for age, though certain types (e.g., VKC) tend to target younger patients.2 The time of year can also give a clue; viral and allergic conjunctivitis are most common in the spring and summer, while bacterial conjunctivitis is most common in the winter.

History of present illness questions may also point toward an etiology. As viral etiologies are often connected with upper respiratory tract infections, asking whether the patient feels sick currently or has felt sick in the past can help differentiate between PCF and EKC, respectively. Patients with viral conjunctivitis will often report recent contact with a sick individual. Bacterial infection is moderately less contagious and more likely to arise de novo. Both bacterial and allergic causes are less commonly linked to an acute bout of illness.

The course of the disease can also be a good diagnostic clue. While allergic conjunctivitis likely is associated with a long course of exacerbation and remission, both bacterial and viral likely have an acute presentation and a protracted (fewer than 14 days) course to improvement. As such, sudden onset of symptoms may point to an infectious cause. Viral infections tend to last longer than bacterial, but neither is likely to recur several times in succession.

Laterality can also be indicative of etiology. Viral conjunctivitis pathognomonically starts in one eye and spreads to the other within a few days, almost always with varying severity. Bacterial conjunctivitis has no clear pattern of laterality and can be unilateral, bilateral or asymmetric. If presenting bilaterally, allergic cases almost always present with varying severity.

Visual acuity. Vision can be notably reduced in adenoviral infections compared with other forms of conjunctivitis, especially in cases with corneal involvement or significant inflammation.

Additional tests. Some cases may warrant specific testing to pinpoint the underlying etiology. AdenoPlus (Quidel Corporation), a point-of-care immunochromatography test for adenoviral infection, takes 10 minutes in-office and is highly sensitive to adenoviral infections. Specificity ranges widely in studies, with some showing high false-negatives. Additional testing is typically not indicated in bacterial conjunctivitis, although severe cases—including those with corneal findings and those suspected to be hyperacute, recurrent or recalcitrant cases—may warrant conjunctival swabs to rule out gonococcal and meningococcal infection. While false-positives are possible (Staphylococcus and Streptococcus are found in normal lid flora and will often show up on the swabs), atypical findings can be diagnostic. Investigations are typically not performed for allergic conjunctivitis.

The most common causes of conjunctivitis are difficult to distinguish based on signs and symptoms alone. With a broader understanding of the various distingushing factors, clinicians will be prepared to diagnose every case of conunctivitis with relative accuracy. Certain combinations have been shown to be predictive; bilateral matting of the eyelids, no itching and no history of conjunctivitis are indicative of a bacterial infection.5 On the other hand, if the patient is also older than six, is presenting between April and November, has watery or no discharge and does not have glued eyes in the morning, this is highly predictive of a negative bacterial culture. Signs and symptoms only form part of the diagnostic picture; other factors, including patient history, are just as crucial to diagnosing the various forms of conjunctivitis.

Dr. Fromstein completed her Doctor of Optometry degree at Nova Southeastern University in Davie, Fla., and pursued a residency in Cornea and Contact Lens at the Illinois College of Optometry, where she is currently an assistant professor and the coordinator of the Cornea and Contact Lens residency program.

1. Azari AA, Barney NP. Conjunctivitis: a systematic review of diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1721-9. 2. Rietveld RP, van Weert HC, ter Riet G, Bindels PJ. Diagnostic impact of signs and symptoms in acute infectious conjunctivitis: systematic literature search. BMJ. 2003;327(7418):789. 3. Kanski JJ. Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach. 6th ed. Edinburgh: Butterworth-Heinemann/Elsevier; 2007. 4. Sethuraman U, Kamat D. The red eye: evaluation and management. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2009;48(6):588-600. 5. Rosario N, Bielory L. Epidemiology of allergic conjunctivitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11(5):471-6, 6. American Optometric Association. Care of the patient with conjunctivitis. Optometric Clinical Practice Guideline. St Louis, MO: American Optometric Association; 2002. 7. Newman H, Gooding C. Viral ocular manifestations: a broad overview. Rev Med Virol. 2013;23(5):281-94. 8. Pavan LD. Ocular viral infections. Med Clin North Am. 1983;67(5):973-90. 9. Høvding G. Acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(1):5-17. 10. Blomquist PH. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections of the eye and orbit (an american ophthalmological society thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2006 Dec;104:322-45. 11. O’Gallagher M, Bunce C, Hingorani M, et al. Topical treatments for blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb 7;2:CD011965. 12. Solano D, Czyz CN. Conjunctivitis, viral. StatPearls https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470271/. Published December 12, 2017. Accessed September 15, 2018. 13. Tarabishy AB, Jeng BH. Bacterial conjunctivitis: a review for internists. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(7):507-12. 14. Rietveld RP, ter Riet G, Bindels PJ, et al. Predicting bacterial cause in infectious conjunctivitis: cohort study on informativeness of combinations of signs and symptoms. BMJ. 2004;329(7459):206-10. 15. Abbott R, Halfpenny C, Zegans M, Kremer P. Bacterial Corneal Ulcers. Duane’s Clinical Ophthalmology, 12th ed. Volume 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2013. |